Early Career Highlight – Dax Soule – Using the OOI to Build Paths for Success in His Students and His Research

Dax Soule builds pathways – the pathway for his own career and the pathways for his diverse student body to move toward theirs. “It is important to recognize that you always have the ability to define what you are doing,” says Soule. “You can take the job you have and make it the job you want.”

Soule is a professor at Queens College (QC) in New York, an undergraduate focused institution that is part of the City University of New York (CUNY) system. CUNY is one of the largest urban public educational systems in the nation with more than 275,000 students in over 24 campuses throughout New York City. QC is one of CUNY’s 11 Baccalaureate/Masters Colleges. Its ~19,000 students mirror the rich ethnic, religious, and linguistic diversity of the residents of the borough of Queens. With large Hispanic (Central and South America), Asian (China, Korea, Vietnam, Malaysia), and Indian sub-continent (India, Pakistan, Bangladesh) populations, QC is officially designated as both an Asian American, Native American, and Pacific Islander-Serving Institution (AANAPISI), and a Hispanic Serving Institution (HSI).

More than half of the students at QC receive need-based financial aid and report an annual household income of less than $30,000. “These students have a unique set of needs,” says Soule. “Even the ones living at home often have to work to help support that home. A lot of these kids have hard backgrounds and noises in their lives that are louder than their academics. It’s my job to help show them the 20,000 foot view; how to take the hard classes, get the degree, get the career, and succeed.”

Soule himself has had what he calls an “improbable path” to his PhD and becoming a professor, so he can empathize with the journey of his students. After an initial start as a working student studying history at Texas A&M, Soule dropped out and worked a variety of jobs before landing as a salesman and eventually the manager at a car dealership in Bryan, Texas.

After a decade in the private sector Soule realized that that was not the path he wanted to be on; he wanted to go back and finish his degree. “I thought that if I died right now my tomb stone would just read, ‘Well… he sold a lot of cars.’ And that wasn’t enough for me,” says Soule.

Back at Texas A&M, Soule re-enrolled in the history department and began by taking a Shakespeare course which just happened to be taught in the Geology building. While the class was debating Hamlet and Macbeth, Soule found himself pondering the oceanographic maps and geologic diagrams hanging on the walls. “I started dreaming, so I called the oceanography department at Texas A&M,” says Soule, “and asked them what I needed to do to become an oceanographer.” Their answer: “get a graduate degree.” Despite all the normal fear associated with being a second career students and no quantitative background, Soule changed his major to Geophysics and started on his new path.

“It is important to recognize that a lot of the pedagogical insight I bring to teaching is because I learned everything I know as a second career student,” says Soule. “I remember I had to ask the professor in my first geology class what sine and cosine were. The entire gradient of learning for me happened in my thirties. As a result, I became really attuned to what worked for me – it was a combination of being used to the deliverables-based environment that made me successful in business and being too afraid of failure to not ask for help that really gave me an advantage.”

After a successful undergraduate research career, including two projects in France collecting near surface geophysical data, one stint as a marine technology intern on R/V Palmer, and a cruise to the Ninety East Ridge in the Indian Ocean, Soule was accepted into the PhD program at the University of Washington (UW) to work with Dr. William Wilcock.

At UW, Soule worked on three main projects: the first was using seafloor seismometers to detect and track the calls of fin whales. The second developed a lower crustal model of the Endeavor segment of the Juan de Fuca Ridge off Vancouver Island. The third project focused on using data as a pedagogical tool.

During his tenure at UW, the also OOI began to take shape. “Though I was not using the data in my own research at the time, I was certainly aware of and in the room for many conversations about the OOI,” says Soule. “I have always known that it would be part of my overall plan for inquiry as a scientist and researcher.”

After graduation, Soule took a tenure track lecturer position at QC with zero research budget. “Teaching positions are a challenge from a research perspective,” says Soule. “I knew my goal was a professorship, so I sought out ways to make the research happen, and the OOI has played a large part of that.”

Much like his own graduate and undergraduate experiences Soule, was also committed to create opportunities for students at QC to do expeditionary level work. “I wanted to create opportunities much in the way they had been created for me,” says Soule. “Along the way in my academic journey the one common thing was the amazing faculty that went out of their way to make things happen for me.”

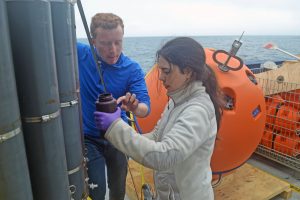

Since Soule arrived at QC he has put eight students on board NSF funded cruises. Four sailed with the OOI on two Visions cruises (2017 & 2018) with Dr. Deb Kelley as part of the Cabled Array annual maintenance cruises. Another four went on a cruise with Dr. William Wilcock also to the Northeast Pacific. In the next few years Soule has plans to send eight more students down to Antarctica on a polar seismic expedition in the Bransfield Strait.

The OOI is also playing a large role is Soule’s research. “I had limited time, no funds, and no data when I joined Queens,” says Soule. “OOI represented a huge opportunity in that I didn’t have to raise any money, all I needed to do was log in and start learning how to use the terabytes of data streaming to my computer. You can ask world changing questions with this network.”

Currently, Soule and his colleagues are exploring two hydrothermal vent fields instrumented by the OOI to try to understand what makes them tick. For example, how is magma stored and delivered to the caldera of Axial Volcano? And how might we better predict when eruptions might occur?

These are tough questions, but the OOI Cabled Array has instruments measuring everything from the chemistry of underwater hot springs, to inflation and deflation of the roof of the volcano, to thousands of seafloor earthquakes. There are photographs and high definition video of some of the most novel organisms on Earth, measurements of tides and waves and pressure fluctuations. “It’s all pieces of a giant puzzle bringing scientists closer than ever to answering the questions that have long seemed unanswerable,” says Soule. “This is one of the first times anyone has been able to aim all systems into one space and ask this type of interdisciplinary question, and it’s free!”

The diverse array of real-time, coregistered data that Soule is working on is a first in the worlds’ oceans. Developing the analytical tools to understand how the processes are related in these novel datasets will pay huge dividends as time goes by and the time series develop. “From a scientific standpoint what interests me is being able to leverage these concurrent instruments to understand these interdisciplinary processes,” says Soule. “We are going to see relationships that we didn’t expect.”

What does the OOI mean to Soule? It means a career. “The OOI is going to be around for 25 years,” quips Soule. “That’s about how long I want to work.” In all seriousness, he sees the OOI as a way to diversify his research portfolio and provide opportunities for his students. With the OOI, he can still work on projects with big ship-going proposal budgets planned several years out, but he can balance those with the free, immediate research he is able to conduct using the OOI. “Being an early career scientist, there is a cyclical-ness to funding and a reality of money,” says Soule. “It takes time for proposals to take shape. And while that is happening the most transformative dataset in the whole world is freely streaming data into your office in real-time.”

“The OOI is like a fire hose with data pouring out,” says Soule. “It’s just there, regardless of whether anyone is using it. If you are brave enough to lean in and just take a sip, just grab a tiny fraction of that data, well that’s enough for a research project right there.”

Soule was recently promoted from lecturer to assistant professor and continues to pave his path, where imagination is the limit and potential is unleashed, both in his students and himself.