Pioneer Data Complements Fisher-Collected Data to Explain Ocean Processes and Fish Distributions

Since 2014, fishers in southern Rhode Island and scientists from Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI) have been working collaboratively to share data and learn from one another. For the past seven years, fishers have been collecting oceanographic data through the Commercial Fisheries Research Foundation’s (CFRF) Shelf Research Fleet and WHOI has shared data collected by the Pioneer Array.

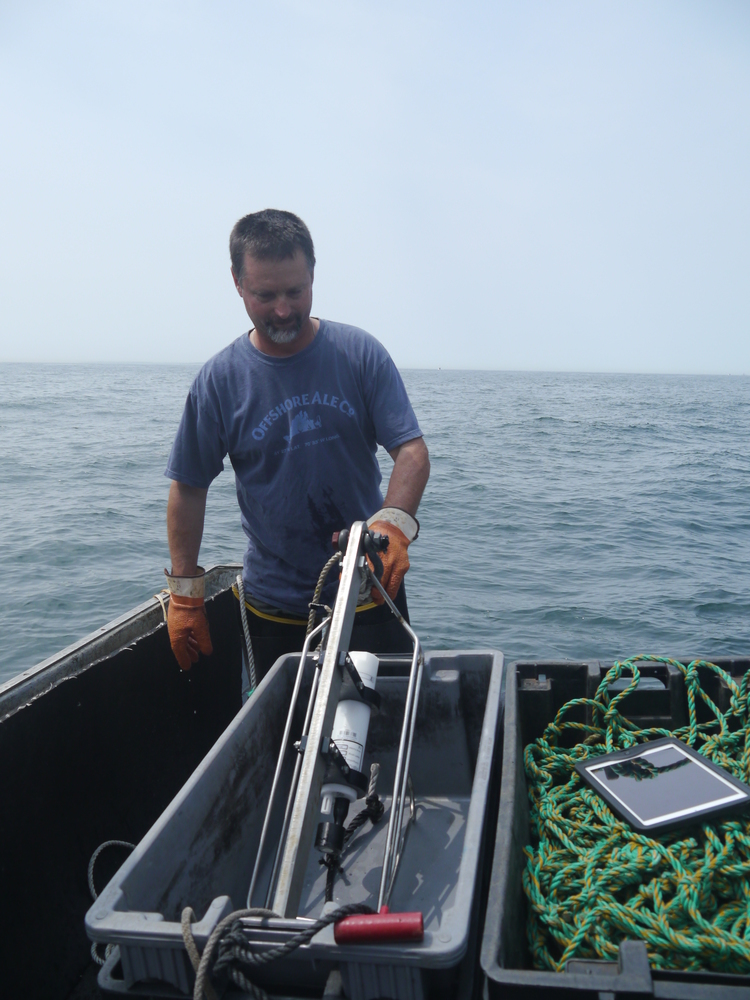

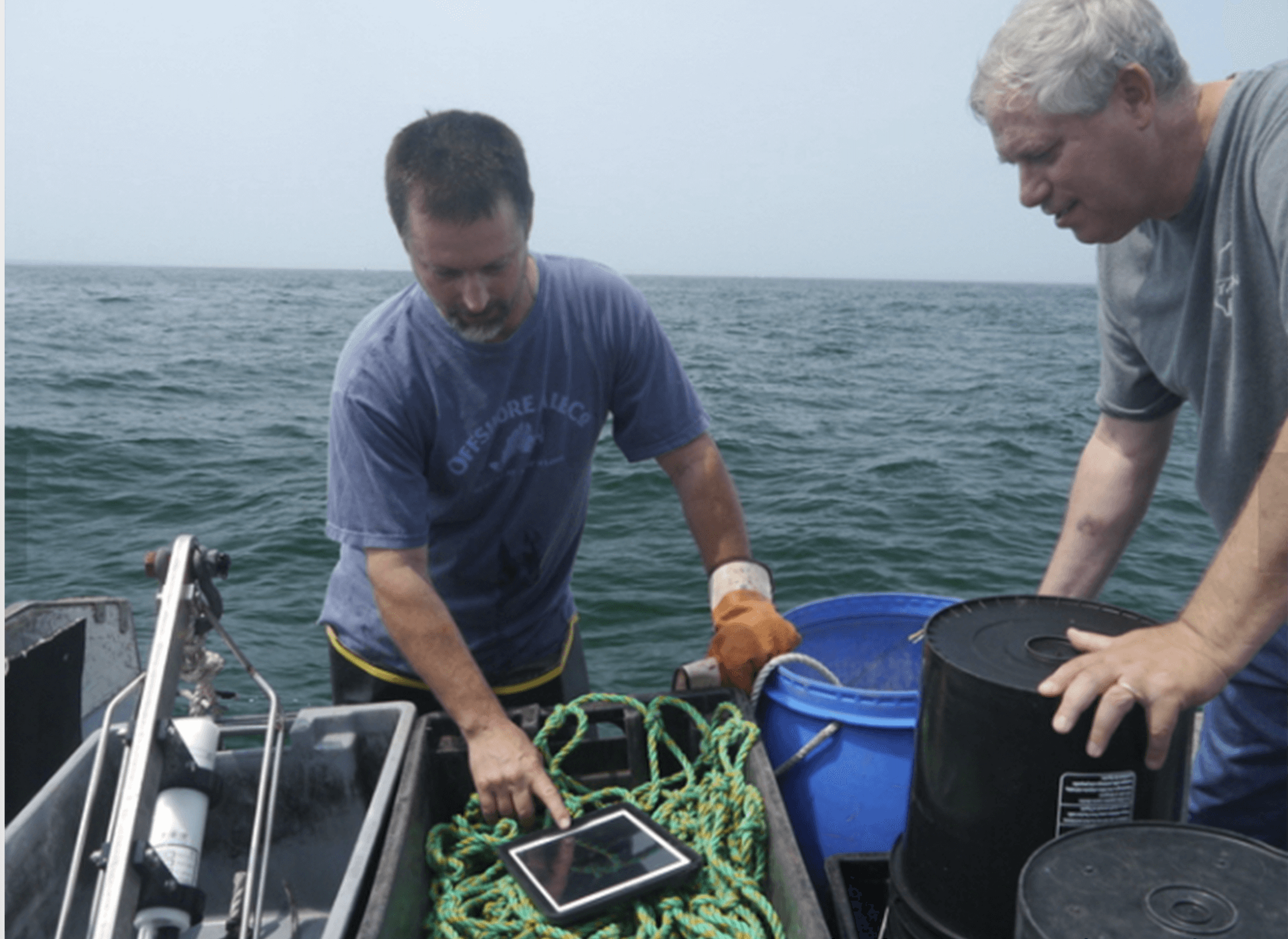

Through this partnership, fishers have come to value data from the Shelf Research Fleet and the Pioneer Array, as well as the insights of researchers who have spent years studying some of the most productive fisheries in U.S. waters. WHOI provides Pioneer data to fishers, and fishers provide oceanographic data collected during their normal fishing operations using CTDs which measure conductivity, temperature and depth information through the CFRF/WHOI Shelf Research Fleet. When the CTDs are brought onboard they wirelessly communicate the temperature data to an iPad where fishermen can view oceanographic conditions and ultimately upload the data to scientists. These CTD measurements provide the physical properties of sea water, which help determine the location and composition of the catch.

Fisher Michael Marchetti (left) and WHOI scientist Glen Gawarkiewicz discuss data collected by a portable CTD. Credit: Commercial Fisheries Research Foundation.

“This arrangement is a good example of how if people are willing to listen and really learn to value issues that are going on for another group, remarkable things can occur,” said Glen Gawarkiewicz, a WHOI researcher who leads the CFRF -WHOI Shelf Research Fleet.

In December, Gawarkiewicz visited the sea surface temperature website maintained by Rutgers University. There he noticed a sea surface temperature image that seemed to suggest a patch of warm, salty water known as a warm core ring forming directly adjacent to the continental shelf in the vicinity of the Pioneer Array. Warm core rings form when the Gulf Stream becomes unstable. These meanders can break off forming a swirling mass of water dozens of miles across, with warm water at the center that can be transported away from the Gulf Stream and into normally cold coastal waters of New England. Once there, such eddies can disrupt ecosystems and affect weather patterns for weeks.

Newport Rhode Island lobsterman James Violet (foreground) reviews oceanographic data collected via CTDs on WHOI provided iPads. Credit: Commercial Fisheries Research Foundation.

Gawarkiewicz then went to the Ocean Observatories Initiative data portal and made plots that confirmed the existence of high-salinity surface water near one of Pioneer’s offshore moorings and near the seafloor of one of the array’s inshore moorings. The conditions, he said, were very much like an event in January 2017 in which fish normally associated with warm Gulf Stream waters were caught near Block Island. The event in January 2017 was initially identified in Shelf Research Fleet data and then confirmed in Pioneer Array glider data analyzed by Robert Todd of WHOI.

Acting on the solid relationship built between WHOI and the CFRF, Gawarkiewicz emailed CFRF staff to warn them that conditions were changing and that they should be on alert for changes in the fishery. Shortly after, he received a phone call from Shelf Fleet collaborator, Aubrey Ellertson, who had reported that fishers were noticing an increase in water temperature on the bottom of the seafloor, and an impact on their catch. For some fishers, the Jonah crab fishing declined, and for others they were not seeing traditional fish species caught in their gillnets.

This exchange highlights the strong partnership between WHOI and the Rhode Island fishing fleet. The collaboration has helped participating fleet members recognize oceanographic processes and relate their fishing catch to processes discussed with WHOI scientists like Gawarkiewicz, and his colleagues Magdalena Andres, Ke Chen, and Massachusetts Institute of Technology/WHOI Joint Program graduate Jacob Forsyth. At the same time, Gawarkiewicz and his team have learned from the fishing community about the impacts of warm core rings on species distribution, their catch and, more broadly, on the shelf ecosystem.

“I knew to pass along this alert because members of the Shelf Research Fleet have taught me about what fishing outcomes are likely from some changing ocean conditions,” said Gawarkiewicz. “It is truly remarkable how much we have been able to learn from each other.”

Gawarkiewicz believes that this event demonstrates both the practical and intellectual value of the Pioneer Array data in improving understanding of sub-surface exchange processes. “Without Pioneer, we would not know the bottom salinity nor been able to give the fishers a heads-up as to what to expect. This shows how Pioneer is having a direct impact on how, when, and where people are fishing.”

To hear an audio piece with interviews with Gawarkiewicz, Aubrey Ellertson and others, listen here.