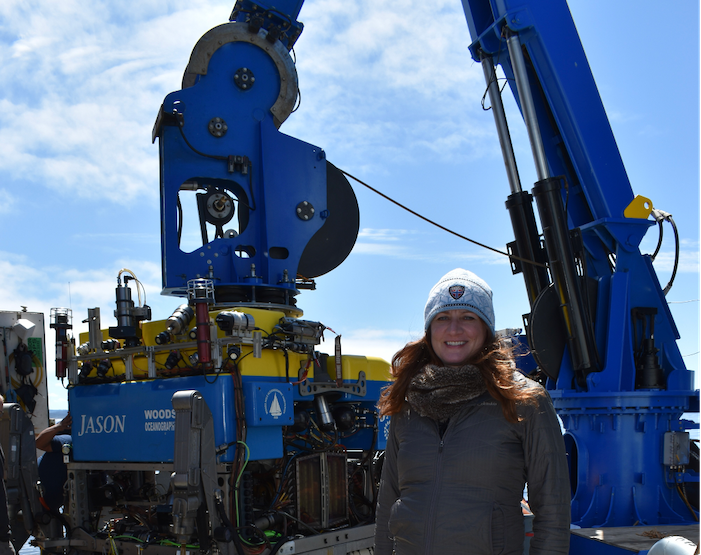

Trina Litchendorf: A Wealth of Sea-going and Engineering Experience

Trina Litchendorf is a highly experienced member of the Regional Cabled Array (RCA) team with a wealth of sea-going and engineering experience. She’s been with the Applied Physics Laboratory (APL) at the University of Washington (UW) since 2001. She started there as an intern through a NASA sponsorship, and stayed on while getting a degree in chemical oceanography at the UW. After graduation, she remained at APL, where she has been involved in keeping ocean observing instrumentation operational ever since. She has been working specifically on RCA instruments since 2013. She was onboard for the first deployment of cabled array instrumentation in 2014, and has served as a key part of every annual expedition since.

Trina’s duties at APL and for the RCA vary by the season. During the spring and early summer, she is actively engaged in testing and building RCA components so that they are ready for the annual Operations and Maintenance cruise. These cruises usually take place in August when undergraduate students join RCA team members at sea as part of the VISIONS at-sea experiential learning program to recover and deploy the infrastructure and instruments that the cable powers.

Each instrument undergoes three rounds of testing. The first is in the winter after the recovered instruments have been refurbished. Each is put through a rigorous round of testing, with a 12-page document of things to check. These procedures cover everything from checking for ground faults to prevent instruments from shorting out in saltwater, to placing them in a large salt water tank to simulate deployment conditions to ensure they work under such conditions. The instruments are also put through a pressure test to simulate seafloor conditions, followed by full functionality testing.

The second and third tests happen directly before the annual cruise and prior to deployment. “The second test is an integration test in the lab. We attach the instruments on the platforms on which they will be deployed to make sure that we can communicate with them and operate them through the platform. Once this test is complete, we are ready for the third, which happens onboard the ship during the annual expedition.” Onboard, she conducts a final test, connecting to the platform again to make sure all the instruments are working before anything goes into the water. She also is ready with spare and replacement parts should anything go awry during this final test.

During the expedition, Trina also directs remotely operated vehicle (ROV) dives, which serves as the eyes, ears, and hands of the underwater operation. She sits in the “hot seat” next to the ROV pilot where she directs activities on the seafloor and in the water column. The pilot manipulates the ROV to execute myriad complex operations she directs. Every platform is a little different so it is necessary to follow a prescribed dive plan to make sure every task is completed in the order in which it is supposed to happen. The complexity of these dives makes for some long days. “Typical dives run anywhere from 3-12 hours or more, and I usually end up pulling one or two 24-hour days while I’m at sea.”

“We have to get all of our gear on the seafloor plugged in and operational and last year’s gear up and off the seafloor,” Trina explained. “We have so much equipment that there’s not enough deck space for all of it, so we break the cruises up into multiple legs to load the next batch of equipment and offload the recovered gear. As a result, these cruises last anywhere from five to six or more weeks.” She’s currently getting ready to depart on VISIONS 22 in August, which because of its scope, is six weeks long and will be conducted in five legs.

Once recovered, another of her jobs is to photograph the platform and instruments’ condition, before helping with clean up, scraping of sea life that has colonized instruments and platforms, and removing a years-worth of additional biofouling.

In the fall, after the cruise is over, Trina’s responsibilities turn to refurbishment and readying the instruments their next deployment. This, too, is a big job. There are close to 150 instruments deployed on more than 30 different types of platforms. The platforms range from junction boxes on the seafloor that serve as power sources for many instruments to benthic experimental packages with their own suite of instruments to shallow and deep-water profilers that move instruments up and down through the water column to sample at various depths. Her task is to ensure that recovered instruments are cleaned, taken apart, and refurbished. Most of the instruments are sent off to vendors for refurbishment and recalibration. The ultimate objective is to ensure that all of the instruments are working and that high quality data are being streamed from the RCA for community use.

The winter, into spring is spent testing and putting the platforms and instruments back together again in preparation for the upcoming cruise as the cycle begins again.

Trina’s favorite part of her job is her time at sea, particularly the time she spends in the control van with the ROV team. There she also runs the science camera, which gives her an inside look into a world few others have the opportunity to see. “I’m seeing things that most people only get to see on the Discovery Channel or National Geographic. It really is a great privilege to be part of that.”

And, she sees the cabled array as a vision realized. “I remember Dr. John Delaney telling us (during one of her undergraduate oceanography classes) about this idea he had to put a large cable in the water to power multiple seafloor sensors to study the ocean and that the whole paradigm of how oceanographic research was conducted was going to change. He saw it as moving from the old model of going out to sea on research vessels for just a few weeks at a time to collect data, to having a 24/7 365–day presence on the seafloor and throughout the water column streaming data in real time to scientists all over the world. And here I am now, actually doing this work and helping this science happen. It’s amazing,” she concluded.