Canadian and OOI Gliders Meet in Pacific

In an important collaborative undertaking, the Ocean Observatories Initiative (OOI) Glider 363 and a Fisheries and Oceans Canada (DFO) Glider crossed paths along Line P, a transect line in the northeast Pacific. This modern day “intersection” provides an opportunity for scientists to have co-located science profiles to match up with sensor data, but also an efficient way to extend data about ocean conditions along Line P throughout the year.

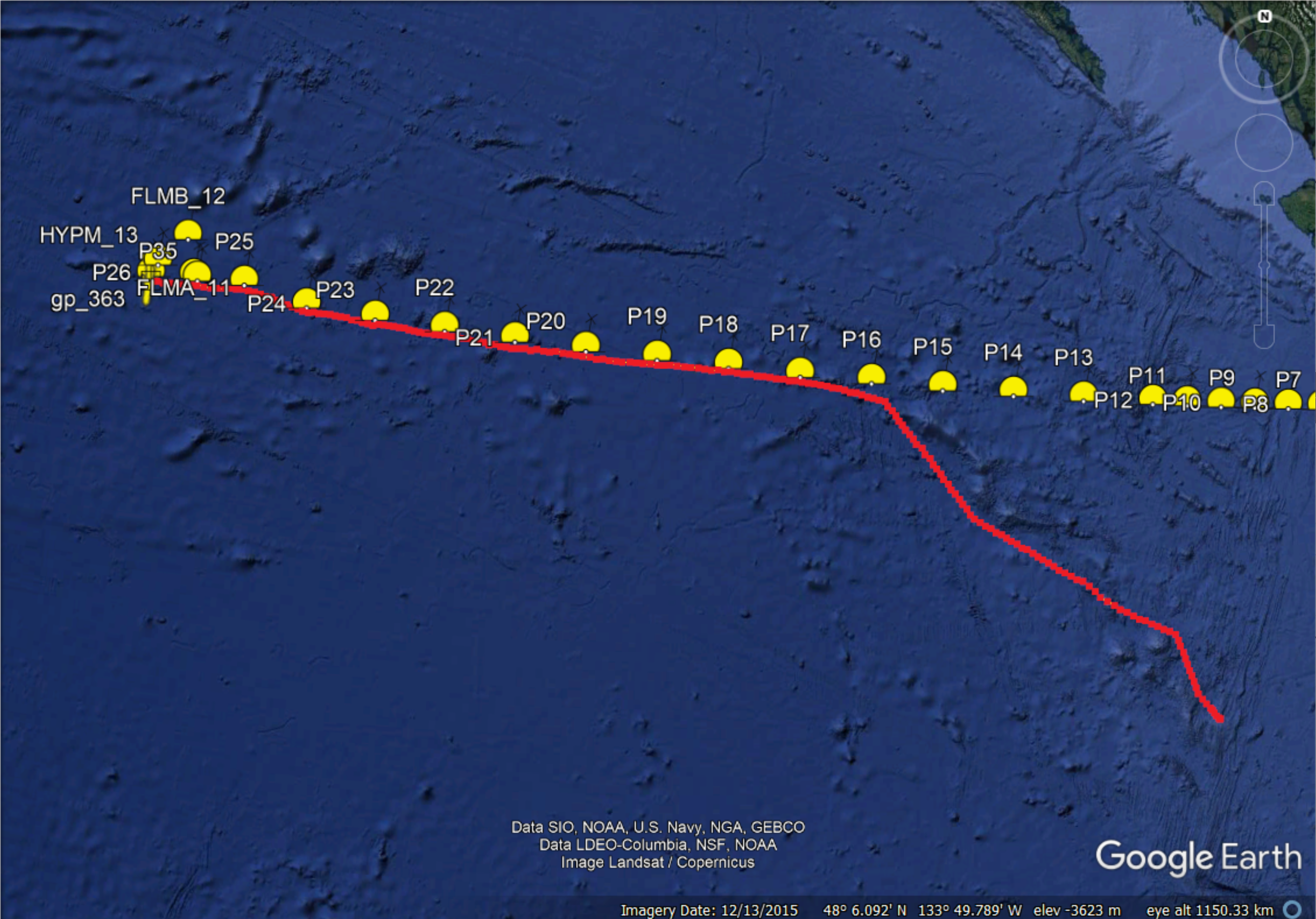

Line P consists of 27 stations extending from Vancouver Island to Ocean Weather Station Papa (OWSP), also known as “Station Papa.” OSWP (located at 50°N, 145°W) has one of the oldest oceanic time series records dating from 1949-1981. This 32-year-old record is supplemented by data collected by shipboard measurements along Line P conducted by DFO three times/year. The US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration also has a surface mooring at Station Papa, which contributes year-round data to this important record. Beginning in 2014, OOI also enhanced Station Papa with an array of subsurface moorings and glider measurements.

An important intersection

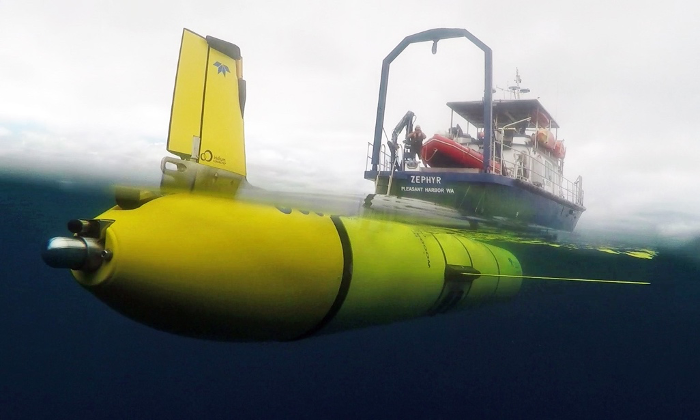

The DFO glider was deployed in late May returning from OWSP. The OOI glider left from Newport, OR aboard the RV Zephyr and was deployed on July 3 at 46 N 130W in open ocean over the Juan de Fuca Ridge. The glider transited along Line P to OOI’s Global Station Papa Array starting from station P16, which is in international waters just outside the Canadian EEZ. A DFO glider was traversing Line P at the same time, providing an opportunity for US and Canadian scientists to have co-located profiles to match up with sensor data.

At the point of the cross-over the OOI glider had been at sea for about 40 days. Both OOI’s and DFO’s glider have very similar sensors onboard that measure temperature, salinity, pressure, oxygen, optical backscatter, chlorophyll, and colored dissolved organic matter. These measurements when compared to historical data provide insight into existing and possibly changing conditions in the water column.

“At a very basic level these deep-ocean rendezvous provide us with an opportunity to compare the sensor data mid-deployment, instead of just at the start or end of their respective deployments. This can help us look for any trends or offsets that might indicate sensor issues – such as aging, fouling, and other issues that may impede performance. This information helps people understand and be able to use data from these gliders,” explained Peter J. Brickley, OOI’s Glider Lead. “The other outcome is that our joint glider data can contribute extra sampling along Line P. While there are several cruises along this line every year, those efforts are spaced far apart in time (sometimes several months). Autonomous gliders can fill some of the gaps, are relatively inexpensive to operate, and can help better delineate conditions, including changing anomalies as they occur.”

Another contributing factor to making this initial glider cross-over a useful test case is that a scheduled DFO Line P cruise on the Canadian Coast Guard Ship John P. Tully was happening concurrently along Line P. The team aboard the Tully started sampling in early August and are scheduled to complete sampling by the month’s end. The ship collected some data in the vicinity of both gliders, offering another opportunity to compare and contrast data.

While the glider cross-over is an important first, it is emblematic of the ongoing cooperative effort between the Canadian DFO, NOAA, and OOI teams sampling in this important region. Communications occur regularly between OOI team members and the Chief Scientist conducting DFO shipboard sampling, as well as between OOI and NOAA personnel.

Added Brickley, “This recent excursion along Line P was planned, but also a serendipitous opportunity that could be leveraged quickly. Once we all have the chance to assess the data provided, we’ll be in a better position to explore making this a more regular occurrence. If it turns out that our sampling schemes are easily aligned, that could be another step to help advance understanding of ocean processes from coastal, eutrophic waters into the heart of the high nitrate, low chlorophyll area of the NE Pacific.”