Accounting for Ocean Waves and Current Shear in Wind Stress Parameterization

Ortiz-Suslow et al. (2025) use measurements of direct covariance wind stress, directional wave spectra, and current profiles from the OOI Coastal Endurance Array (Ocean Observatories Initiative) offshore of Newport, Oregon (2017–2023) to test a proposed new general framework for the bulk air-sea momentum flux that directly accounts for vertical current shear and surface waves in quantifying the stress at the interface. Their approach partitions the stress at the interface into viscous skin and (wave) form drag components, each applied to their relevant surface advections, which are quantified using the inertial motions within the sub-surface log layer and the modulation of waves by currents predicted by linear theory, respectively.

Their framework does not alter the overall dependence of momentum flux on mean wind forcing, and they found the largest impacts at relatively low wind speeds. Below 3 m s−1, accounting for sub-surface shear reduced form drag variation by 40–50% as compared to a current-agnostic approach. As compared to a shear-free current, i.e., slab ocean, a 35% reduction in form drag variation was found. At low wind forcing, neglecting the currents led to systematically overestimating the form stress by 20 to 50% — an effect that could not be captured by using the slab ocean approach. Their framework builds on the existing understanding of wind-wave-current interaction, yielding a novel formulation that explicitly accounts for the role of current shear and surface waves in air-sea momentum flux. Ortiz-Suslow et al. find their work holds significant implications for air-sea coupled modeling in general conditions.

In using the Oregon Shelf (CE02SHSM) data, Ortiz-Suslow et al. note, “There are several distinct advantages to using these data for this analysis: (1) the range of the dataset goes back seven years with good temporal coverage, (2) there are co-located wind, wave, and current measurements at hourly intervals for in-depth analysis, and (3) the site is exposed to a wide range of wind, wave, and current conditions. Furthermore, by using this dataset, we take advantage of internal quality data control and processing steps that are standardized across the OOI array network.”

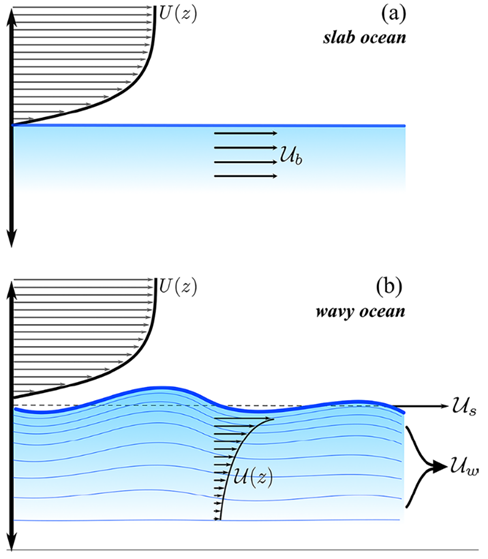

Conceptual diagram highlighting the distinction between defining the relative wind velocity over the (a) slab ocean versus the (b) wavy interface. In the presence of near-surface shear, the relative contributions of viscous skin (Us) and wave form (Uw) must be directly accounted when calculating the relative wind at the base of the sheared wind profile (Figure 30, Ortiz-Suslow et al., 2025).

___________________

Reference:

Ortiz-Suslow, D.G., N. Laxague, J-V. Björkqvist, M. Curcic, (2025). Accounting for Ocean Waves and Current Shear in Wind Stress Parameterization. Boundary-Layer Meteorology, 191(38), https://doi.org/10.1007/s10546-025-00926-9