News

Mission Accomplished: Endurance 14 Cruise Meets All Objectives

After a 15-day expedition, the Endurance Array Team returned to port aboard the R/V Sikuliaq on 7 April having successfully completed the 14th turn of the Endurance Array. The team recovered and deployed seven surface moorings and completed sampling at all recovery/deployment sites. They also deployed and recovered gliders and surface profilers.

Because of the size and weight of the moorings and other equipment, the trip was conducted in two legs. The first leg was primarily off Washington and the second off Oregon. Between legs, the R/V Sikuliaq returned to Newport, Oregon to offload recovered equipment from the Washington Line and load new equipment for the Oregon Line.

The weather was rough when the R/V Sikuliaq first set off from Newport on 24 March. On the first night out, they saw 19-foot waves and 35-knot winds. The team worked around the weather on the first leg to deploy three moorings and recover four. They also recovered and deployed gliders.

The second leg of the journey brought with it much better weather, which eased the recoveries, deployments, sampling, and other activities. During this leg, the team worked mostly off Oregon. The team deployed four moorings and three profilers and recovered three moorings, three gliders, and a profiler.

Each OOI deployment brings some technical improvement. On this deployment, the Endurance moorings are outfitted with redesigned solar panels on the buoy decks. These panels will deliver more power and be more resilient to wear and tear caused by sea lions who often find the buoys an inviting place to lounge. The redesign was implemented by OOI’s Coastal and Global Scale Nodes team at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution.

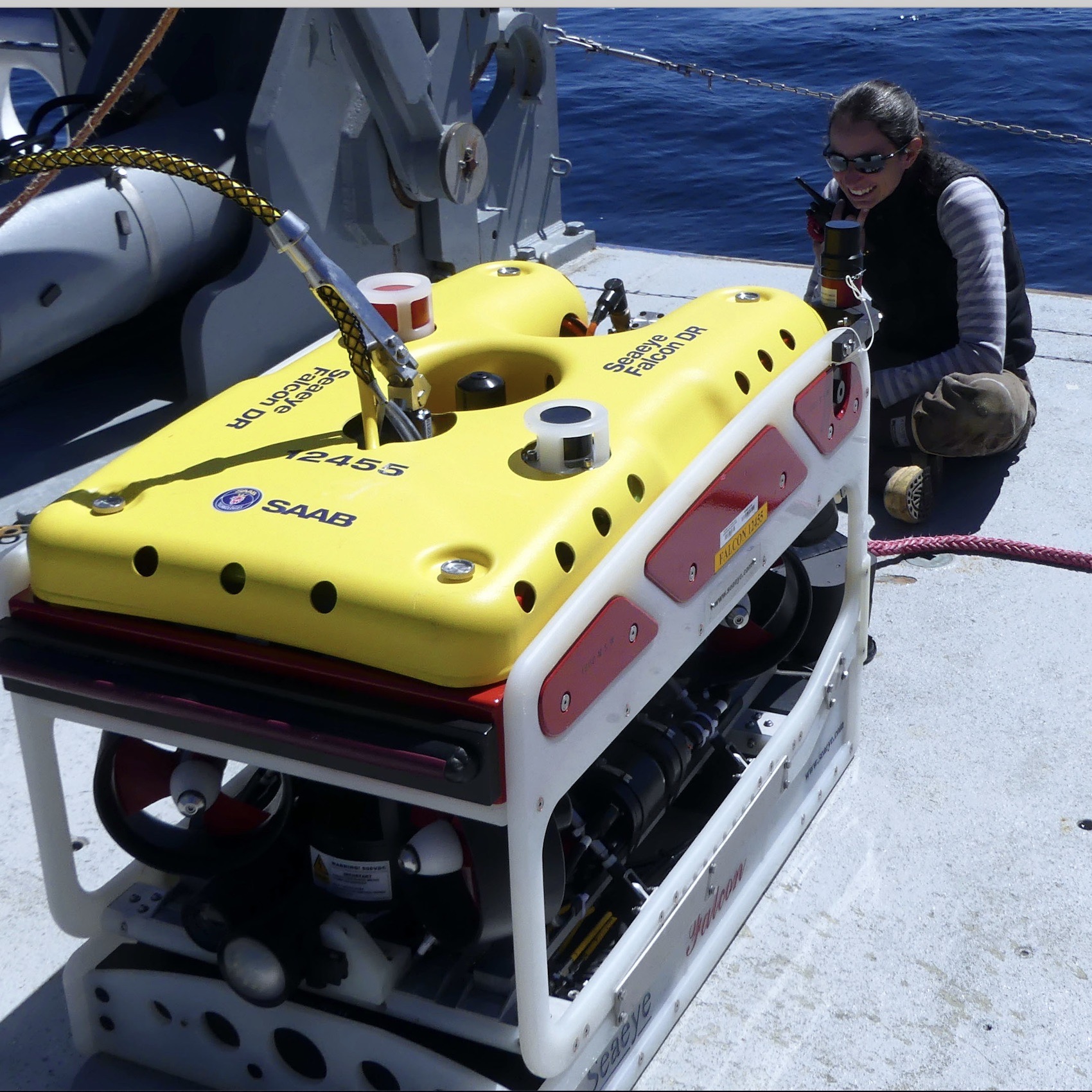

This trip also marked the Endurance Array’s team first use of a OOI’s ROV (remotely operated vehicle). The ROV was used at the Oregon shelf site to recover a coastal surface piercing profiler and its anchor. Throughout the process, the R/V Sikuliaq maneuvered skillfully to place the ship over the target. Mooring lead Alex Wick piloted the ROV through strong currents and limited visibility. It took four dives, but the profiler and its anchor were recovered. On the third dive, the ROV was used to cut the winch line so the team could recover the profiler, and the anchor was recovered on the fourth and final dive.

The Endurance team also collected CTD samples and biofouling samples to share with researchers at the Smithsonian Institute and Oklahoma State University. The R/V Sikuliaq returned to Newport on 7 April with the recovered equipment, which will undergo refurbishment for the next turn of the Endurance Array in September.

“Since 2017, we’ve sailed on the R/V Sikuliaq for six out of nine cruises,” said Ed Dever, the Chief Scientist of Endurance 14. “It’s a match that works well. From ship handling and on-deck assistance to mobilization of underway science sensors, lifting gear, engineering, accommodations, and food, we are deeply appreciative of the Sikuliaq’s captain, crew, and the ship herself.”

Read MorePioneer Data Now on New Mariners’ Dashboard

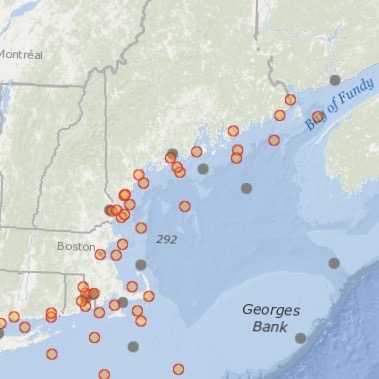

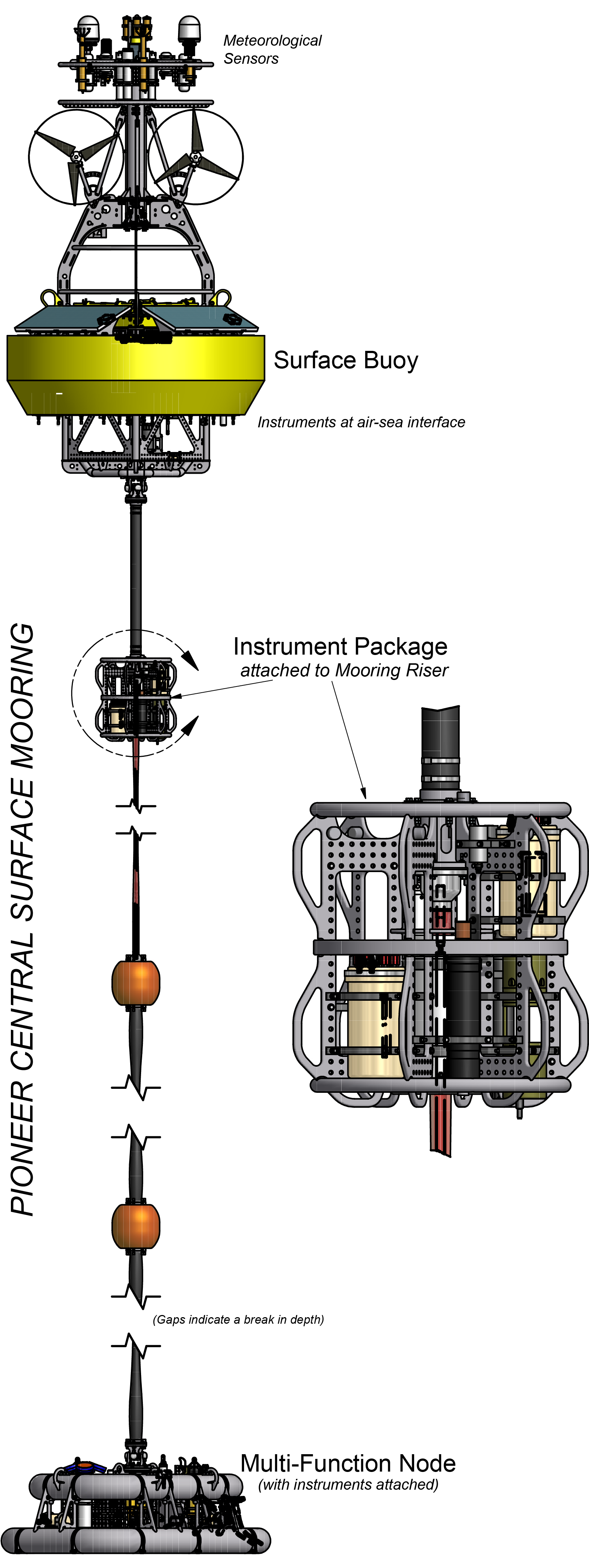

Data from three of the Ocean Observing Initiative’s (OOI) Pioneer Array buoys are now part of the Mariners’ Dashboard, a new ocean information interface launched by our partners at NERACOOS (Northeastern Regional Association of Coastal Ocean Observing Systems). Visitors can use the Dashboard to explore the latest conditions and forecasts from the Pioneer Inshore, Central, and Offshore mooring platforms, in addition to 30+ other observing platforms throughout the Northeast.

The Mariner Dashboard delivers high-quality, timely data from a growing network of buoys and sensors into the hands of mariners heading to sea. The data provided by the Pioneer moorings are particularly valuable because there are few other observing platforms in the highly traveled and productive shelf break region.

Observations provided range from air pressure and temperature, sea surface temperature, wave height, direction, velocity, and duration to salinity. Check out the Pioneer Array’s contributions to the wealth of information on the new Mariners’ Dashboard here:

[caption id="attachment_20963" align="alignleft" width="113"] Components used to collect and transmit ocean observations to shore.[/caption]

Components used to collect and transmit ocean observations to shore.[/caption]

Pioneer offshore https://mariners.neracoos.org/platform/44077

Pioneer central: https://mariners.neracoos.org/platform/44076

Pioneer inshore: https://mariners.neracoos.org/platform/44075

“We are pleased to see the Pioneer Array data being made more widely available through the Mariners’ Dashboard to help provide information about current ocean conditions,” said Al Plueddemann, head of the Ocean Observatories Initiative Coastal and Global Surface Nodes team, which includes the Pioneer Array. “This is just one example of how OOI data, which are freely available to anyone with an Internet connection, are being put to good use.”

Read More

Applications Open for Larry P. Atkinson Travel Fellowship

Do you need travel funds to attend and present your OOI research at a conference?

Larry P. Atkinson[/caption]

Larry P. Atkinson[/caption]

The Larry P. Atkinson Travel Fellowship for Students and Early Career Scientists online application is now open!

If you need funding to offset conference expenses (registration fees, travel costs, accommodations, etc.), we encourage you to apply. Conference participation can be in-person or virtual. Information on eligibility requirements, and how to apply, are available here.

Demo of Data Explorer 1.1 Video

Data Explorer continues to be refined in response to data users’ suggestions. Upcoming updates and refinements are previewed in this 55-minute video. The new, improved site will launch 5 May 2021. Look for it!

[embed]https://youtu.be/WhXgQ5qe78E[/embed] Read More

A Bountiful Sea of Data: Making Echosounder Data More Useful

[media-caption path="https://oceanobservatories.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/Screen-Shot-2021-03-30-at-5.51.41-PM.png" link="#"]Researchers used echosounder data from the Oregon Offshore site of the Coastal Endurance Array to develop a new methodology that makes it easier to extract dominant patterns and trends.[/media-caption]The ocean is like a underwater cocktail party. Imagine, as a researcher, trying to follow a story someone is telling while other loud conversations are in the background of a recording. This phenomenon, known as the “Cocktail Party Problem,” has been studied since the 1950s (Cherry, 1953; McDermott, 2009). Oceanographers face this challenge in sorting through ocean acoustics data, with its mixture of echoes from acoustic signals sent out to probe the ocean.

Oceanographer Wu-Jung Lee and data scientist Valentina Staneva, at the University of Washington, teamed up to tackle the challenge in a multidisciplinary approach to analyze the vast amounts of data generated by echosounders on Ocean Observatories Initiative (OOI) arrays. Their findings were published in The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, where they proposed a new methodology that uses machine learning to parse out noisy outliers from rich echosounder datasets and to summarize large volumes of data in a compact and efficient way.

This new methodology will help researchers use data from long time series and extract dominant patterns and trends in sonar echoes to allow for better interpretation of what is happening in the water column.

The ocean is highly dynamic and complex at the Oregon Offshore site of the OOI Coastal Endurance Array, where echosounder data from a cabled sonar were used in this paper. At this site, zooplankton migrate on a diurnal basis from a few hundred meters to the surface, wind-stress curl and offshore eddies interact with the coastal circulation, and a subsurface undercurrent moves poleward. The echosounder data offer opportunities to better understand the animals’ response to immediate environmental conditions and long-term trends. During the total eclipse of the Sun in August 2017, for example, echosounders captured the zooplankton’s reaction to the suddenly dimmed sunlight by moving upwards as if it was dusk time for them to swim toward the surface to feed (Barth et al, 2018).

Open access of echosounder datasets from the OOI arrays offers researchers the potential to study trends that occur over extended stretches of time or space. But commonly these rich datasets are underused because they require significant processing to parse out what is important from what is not.

Echosounders work by sending out pulses of sound waves that bounce off objects. Based on how long it takes for the reflected echo to come back to the sensor, researchers can determine the distance of the object. That data can be visualized as an echogram, an image similar to an ultrasound image of an unborn baby.

But unlike an ultrasound of a baby, when an undersea acoustic sensor records a signal, it may be a combination of signals from different sources. For example, the signal might be echoes bouncing off zooplankton or schools of fish.

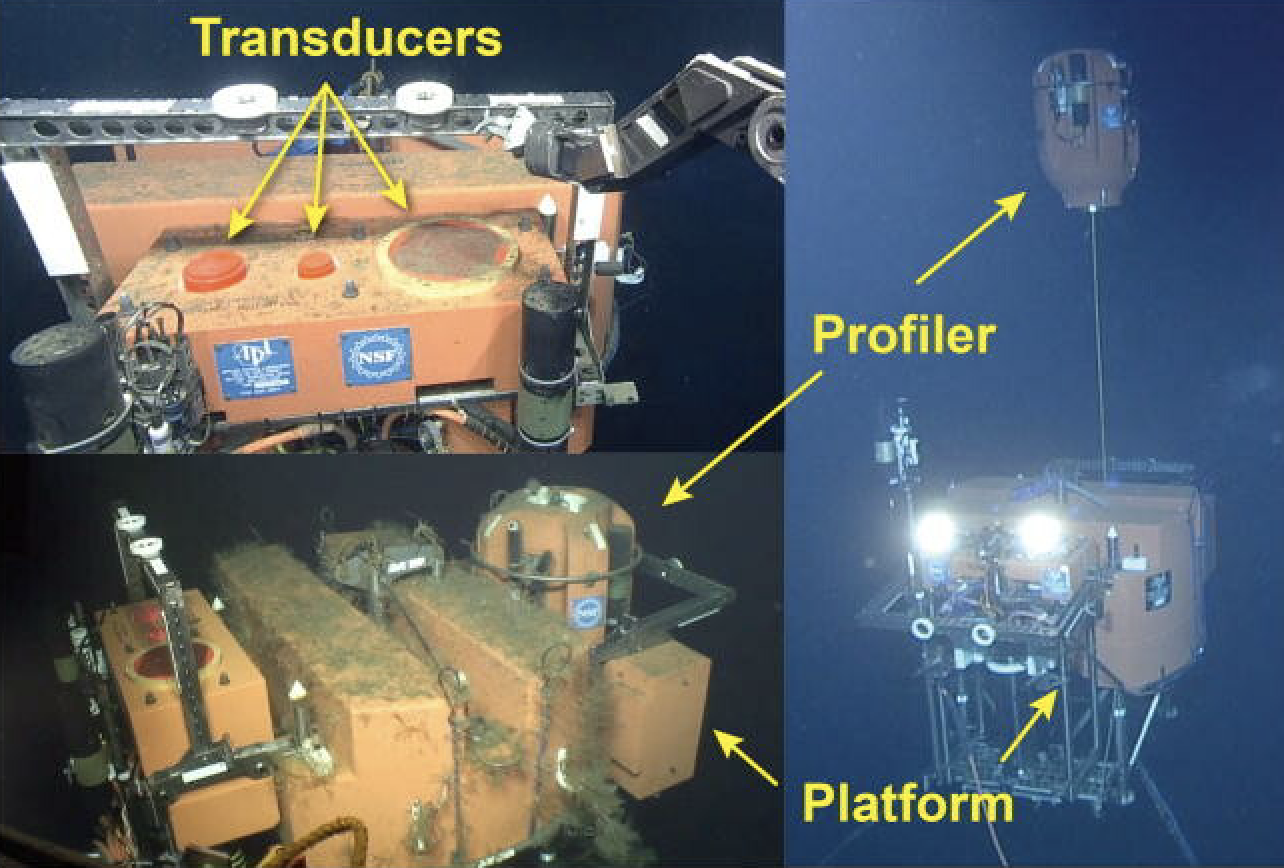

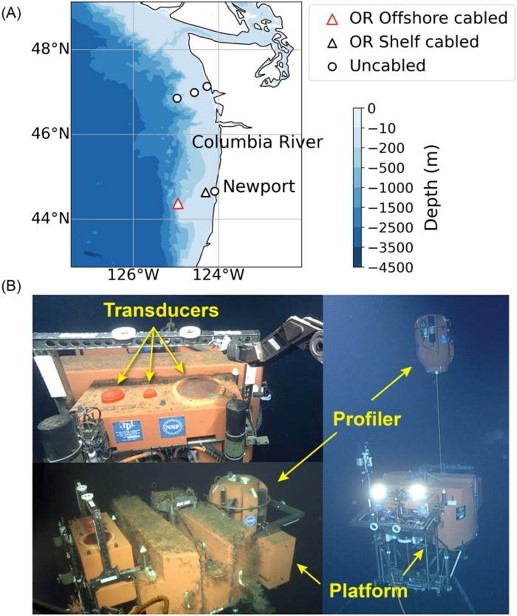

[caption id="attachment_20566" align="alignleft" width="350"] (A) Data used in this work were collected by a three-frequency echosounder installed on a Regional Cabled Array Shallow Profiler mooring hosting an underwater platform (200 m water depth) and profiler science pod located at the Oregon Offshore site of the OOI Coastal Endurance Array (red triangle). The symbols indicate the locations of all OOI echosounders installed along the coast of Oregon and Washington. (B) The transducers are integrated into the mooring platform (from left to right: 120, 200, and 38 kHz). The platform also hosts an instrumented profiler that traverses the water column above the echosounder from ~ 200 m to ~ 5m beneath the ocean’s surface. (Image credit: UW/NSF-OOI/WHOI-V15).[/caption]

(A) Data used in this work were collected by a three-frequency echosounder installed on a Regional Cabled Array Shallow Profiler mooring hosting an underwater platform (200 m water depth) and profiler science pod located at the Oregon Offshore site of the OOI Coastal Endurance Array (red triangle). The symbols indicate the locations of all OOI echosounders installed along the coast of Oregon and Washington. (B) The transducers are integrated into the mooring platform (from left to right: 120, 200, and 38 kHz). The platform also hosts an instrumented profiler that traverses the water column above the echosounder from ~ 200 m to ~ 5m beneath the ocean’s surface. (Image credit: UW/NSF-OOI/WHOI-V15).[/caption]

“When the scatterers are of different size, they will reflect the sound at different frequencies with different strengths,” said Lee. “So, by looking at how strong an echo is at different frequencies, you will get an idea of the range of sizes that you are seeing in your echogram.”

Current echogram analysis commonly requires human judgement and physics-based models to separate the sources and obtain useful summary statistics. But for large volumes of data that span months or even years, that analysis can be too much for a person or small group of researchers to handle. Lee and Staneva’s new methodology utilizes machine learning algorithms to do this inspection automatically.

“Instead of having millions of pixels that you don’t know how to interpret, machine learning reduces the dataset to a few patterns that are easier to analyze,” said Staneva.

Machine learning ensures that the analysis will be data-driven and standardized, thus reducing the human bias and replicability challenges inherently present in manual approaches.

“That’s the really powerful part of this type of methodology,” said Lee. “To be able to go from the data-driven direction and say, what can we learn from this dataset if we do not know what may have happened in a particular location or time period.”

Lee and Staneva hope that by making the echosounder data and analytical methods open access, it will improve the democratization of data and make it more usable for everybody, even those who do not live by the ocean.

In the future, they plan to continue working together and use their new methodology to analyze the over 1000 days of echosounder data from the OOI Endurance Coastal and Regional Cabled Array region.

References

Lee, W-J and Staneva, V (2021).Compact representation of temporal processes in echosounder time series via matrix decomposition. Special Issue on Machine Learning in Acoustics. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America.

Barth JA, Fram JP, et al. (2018). Warm Blobs, Low-Oxygen Events, and an Eclipse: The Ocean Observatories Initiative Endurance Array Captures Them All.Oceanography, Vol 31.

McDermott, J (2009). The Cocktail Party Problem.Current Biology, Vol 19, Issue 22.

Cherry EC (1953). Some Experiments on the Recognition of Speech, with One and Two Ears.The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. Vol. 25, No.5.

Read More

Spring Expeditions: Keeping OOI Arrays Fully Operational

OOI teams were in the water on opposite coasts in late March to service the Pioneer and Endurance Arrays. The teams will “turn” the moorings (recover old and deploy new) to keep the arrays continually collecting and reporting data back to shore. This is the 14th turn of the Endurance Array; the 16th for the Pioneer Array.

The Endurance 14 Team set sail from Newport Oregon aboard the R/V Sikuliaq on 24 March for a 15-day expedition. The Pioneer 16 Team departed from Woods Hole, MA, a few days later on 29 March aboard the R/V Armstrong for a 21-day mission. Both expeditions will require two legs because of the need to transport a huge amount of equipment. The equipment for the Pioneer Array weighs more than 129 tons. The Endurance equipment tops the scale at 95 tons.

Departures for both teams occurred after arranging for reduced occupancy on site and social distancing during preparation, followed by 14 days of quarantine to meet COVID-19 restrictions. And while onboard, COVID has necessitated other changes ranging from smaller science parties to scheduled meal times to allow for social distancing.

“It is very impressive that the OOI team has been able to continue to service these arrays in spite of the challenges presented by COVID,” said Al Plueddemann, Chief Scientist of the Pioneer 16 Expedition. “The ocean is a tough environment in which to keep equipment operational, even in normal times. This year, in particular, has required both our shore-based staff and those onboard to be adaptable, flexible, and innovative to get the job done.”

[media-caption path="https://oceanobservatories.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/burnin_Travis.jpg" link="#"]The full cycle of preparation for an OOI mooring service cruise takes many months. The “burn-in” period for Pioneer-16, during which equipment is assembled and tested, began in January 2021 with snow on the ground outside of the LOSOS building on the WHOI campus. Credit:Rebecca Travis © WHOI.[/media-caption]In addition to the mooring and deployment recoveries, both teams are deploying and recovering gliders that collect additional data within the water column and the area between the moorings. They also are conducting CTD casts and water sampling at the mooring sites, and doing meteorological comparisons between ship and buoys. The Pioneer Team will be operating autonomous underwater vehicles (AUVs), while the Endurance Team will have its inaugural use of OOI’s own remotely operated vehicle (ROV) to recover anchors at the Oregon shelf site.

“In normal times, we would invite external students and scientists along to conduct ancillary experiments on the cruise,” said Edward Dever, Chief Scientist for Endurance 14. “But given the limited science party allowed onboard due to COVID-19, the OOI team will be conducting some of this additional work to ensure the continuity of these experiments.”

For Endurance 14, this work includes collection of organisms that grow on panels attached to Endurance buoys for invasive species research, collection of settling organisms on devices attached to Multi-Function Nodes, which power near bottom data instruments, and test deployments of tagged fish acoustic monitors on near surface instrument frames on three moorings.

Likewise, the Pioneer 16 Team is helping ensure ongoing science investigations installing and operating unattended underway sampling for the Northeast U.S. Shelf Long-Term Ecological Research (LTER) project and conducting CTD casts at LTER sites during the cruise. They will also conduct communication tests at the Offshore mooring site in support of the Keck-funded 3-D Acoustic Telescope project.

Science teams of 9-10 people on each cruise are sharing the multitude of tasks needed for the moored array service.

[media-caption path="https://oceanobservatories.org/wp-content/uploads//2021/03/Screen-Shot-2021-04-01-at-9.19.20-AM.png" link="#"]OOI’s remotely operated vehicle will be used for the first-time during Endurance 14. Credit: Seaview Systems.[/media-caption]

Read More

Opportunity to Preview Data Explorer 1.1

OOI’s new data access and visualization tool, Data Explorer, has been operational for about six months now. During that time, OOI’s Development Team has been revising it to incorporate input from community users.

We’d like to give the OOI Community an opportunity to preview this next iteration and give us your thoughts. Please join OOI Data Lead Jeff Glatstein and members of the Data Explorer Development Team on 9 April 2021 at 2 pm Eastern. Register here. We will briefly show participants the revised tool and receive any feedback you may have. Our goal is to continually improve this tool to better meet your needs.

Look forward to seeing you in early April.

Read MoreWomen Who Make OOI Happen

[gallery columns="5" ids="28710,28711,28712,28713,28714"]

Keeping OOI operational and providing data around the clock requires a whole team of people working behind the scenes. Because March is Women’s History Month, we have taken the opportunity to ask a few women to share their stories about coming to and working for OOI. By featuring women who contribute to OOI’s success, we honor those women, past and present, who have made OOI possible.

Diana Wickman

Senior Engineering Assistant II

Diana’s job involves the operation, maintenance and piloting of OOI’s fleet of Slocum Gliders and two REMUS 600 AUVs. She is based at Wood Hole Oceanographic Institution.

How did you end up at OOI? When people ask me this question I often say “by accident.” I interviewed with OOI 11 years ago in early 2009 when the program was just kicking off. I had a degree in Marine Science from the University of Connecticut and was wrapping up a four-year stint in the US Air Force as a Satellite Communications Technician – an odd combo to say the least. I applied to be an electrical engineering technician but was instead offered the job of Configuration Manager. I had spent about three years doing configuration management when the program acquired its first Slocum Gliders. I remember walking past the gliders in the hallway one day, so shiny and yellow, and I was immediately hooked. I wanted to know all about these giant “tub toys.” The rest is history.

What is the most challenging part of your job? The most matter-of-fact answer to this question is: keeping the ocean OUT of the inside of the robot, but that is only half of the challenge. The ocean, especially the areas OOI operates in, is really good at breaking things. The OOI Gliders are designed to be deployed with no hands-on human interaction for up to one year at a time. When I’m in the lab working on the gliders I cannot stop at “it is working today,” I need to constantly be thinking “will this remain working for up to a year?” It has been very challenging and also rewarding to learn a system well enough to be able to predict future failures and prevent them before they arise.

What do you enjoy most about your job? I’m only part joking when I tell people the robots are like my kids. They seem to have their own unique “personalities”; some are difficult and some are easy, some seem to love to be deployed and others seem to want to sit in the lab, some are warriors and others wave the white flag at the first sign of trouble. For me, the most rewarding part of the job is seeing the gliders succeed at their missions and come home after their long deployments. Finally getting them on the bench in the lab after a year apart is kind of surreal. I love the story each glider tells of its deployment through the engineering data it gathered at sea. In laying my hands on the vehicle again I become a detective of sorts: did the Glider have a run in with a shark, a near miss with a leak, a collision with an ice berg?

Anything else you’d like to add? Having gone from the Air Force where my particular job was 96% male dominated, to ocean engineering which is also heavily male dominated (although there are many, many brilliant female engineers and engineering technicians at WHOI to look up to), I have no idea what it’s like to work in a non-male dominated career field. Being a woman in a very heavily male dominated career field has its challenges. There have been times I have been the only woman in a meeting, or on a vessel during a cruise (and often in those cases have been the one in charge). I have experienced people make assumptions about my role on the team, or my ability to do my job due to my gender. Luckily for me I’m loud, largely oblivious, and occasionally overconfident, which has helped me break through some of those gender assumptions that may have held other women back. For these traits I both thank and blame my paternal Grandmother.

Trina Litchendorf

Oceanographer IV

Trina is part of the OOI instrument team at the University of Washington’s Applied Physics Laboratory, where they test, maintain and deploy all the commercially-produced instrumentation on the Regional Cabled Array.

What does your job entail?

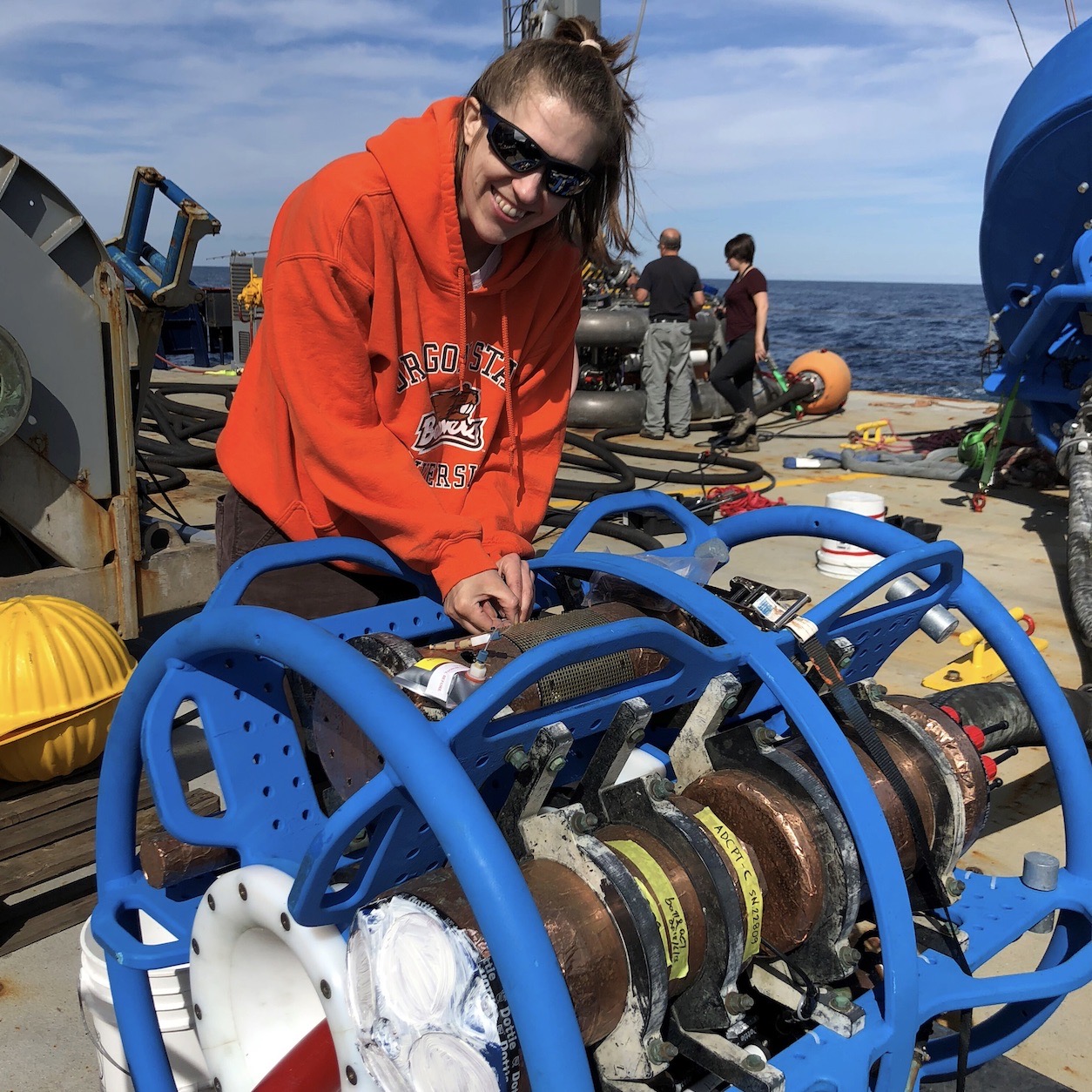

There are over two dozen different types of oceanographic instruments deployed on the Regional Cabled Array – from A to Z – ADCPs (acoustic Doppler current profilers) to zooplankton sonars, and everything in between: CO2 and pH sensors, CTDs, digital still cameras, fluorometers, hydrophones, oxygen optodes, seismometers, and velocity sensors, to name a few. Every summer I go to sea off the Oregon and Washington Coast with the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution’s Jason remotely operated vehicle (ROV) team. The ROV team recovers all of the instrument platforms that were deployed the previous year and then deploys and connects new instrument platforms. After the cruise, in the fall, we send all of the instruments recovered during the cruise, about 135 of them, to their manufacturers so the instruments can be refurbished and calibrated. The instruments start coming back from servicing in the late fall and throughout the winter. During that time, I thoroughly test the instruments to ensure they are working perfectly before they are mounted on their deployment platforms in the spring. Then they go through a round of integration testing on the platforms before the cruise. All of this careful testing ensures high-quality data and a low failure rate once the instruments are deployed. Come summer, I am back out at sea, ready to repeat the yearly maintenance cycle.

How did you end up in this job? I started working at the Applied Physics Lab as a full-time employee in 2001. The projects I have worked on since then have involved everything from lasers, gas chromatographs, and infra-red imagers to underwater vehicles, such as Seagliders and REMUS AUVs (autonomous underwater vehicles). I also have been to sea numerous times for those projects. My familiarity with various oceanographic equipment and my sea-going experience made for a natural fit for the RCA Instrument Team, which I joined in 2015.

What is the most challenging part of your position? The cruises are the most challenging. They average about 40 days, give or take, and the work is non- stop. ROV operations happen around the clock and there is always a lot to do to get the instrument platforms ready to be deployed for the next dive. Every instrument must be powered on for one final check, the platforms must be rigged properly for the ROV, and every instrument on the platform must be photographed before we send it over the side. I also run some of the dives, sitting to the left of the ROV pilot in the control van and telling him or her the order of operations and which cables to plug in. These dives can sometimes last 12 hours or more and I usually pull a few all-nighters. During cruises, we have to come into port several times to offload all the recovered gear and load the next set of equipment, which we try to accomplish in a day or two. The cruises are like marathons and require a lot of stamina. It is also hard to be away from friends and family for so long, especially during the summer when Seattle has its best weather and I’m wearing a down jacket and wool cap because it’s so overcast and cold offshore.

What do you enjoy most about your job? The cruises. As challenging as they are, the cruises also offer the greatest rewards. I enjoy working with the undergraduate students who go to sea with us for their first oceanographic cruises; their enthusiasm reminds me of my first time at sea. There are beautiful sunrises and sunsets to see, the full moon shining on the ocean is stunning, and on moonless nights, the Milky Way is visible and the stars are spectacular. Whales and dolphins occasionally swim by, and there are incredible things to see on the seafloor with the ROV’s HD (high-definition) cameras. My favorite part of the cruise every year is when we do photo-surveys of the hydrothermal vent fields and the lava flows at Axial Caldera. Seeing the interesting biology that lives at these depths and the unique lava and vent formations never gets old!

Anything else you’d like to add? In the early 2000’s, when I was an oceanography undergrad at the University of Washington, my Geological Oceanography course was taught by Drs. Deb Kelly and John Delaney. One day, Dr. Delaney gave a presentation to our class and described a revolutionary way the oceans would be studied in the future: with regional scale ocean observatories that could send data, in real time, over the Internet to scientists around the world. This was years before the Canadian NEPTUNE array, the world’s first such underwater observatory, had been deployed. I remember thinking what a fascinating idea that was. It’s amazing now to be a part of it all, going to sea alongside Dr. Kelly, and deploying the instruments that I tested on the array. I look forward to the future and a day when Dr. Delaney’s other vision is a reality: resident AUVs stationed year-round on the Regional Cabled Array, ready to be deployed immediately after an event such as an eruption at Axial Seamount.

Meghan Donohue

Senior Engineering Assistant I Meghan’s job is ever-evolving. She recently changed from being a mooring tech at Wood Hole Oceanographic Institution, who served as the deck lead on multiple OOI cruises, to being a full-time OOI tech, who preps and builds the moorings for the cruises. Her new position allows her to play more with the computer side of things rather than focusing solely on mechanical issues.

How did you end up at OOI? I was a hyper-focused child who knew from a very young age that I wanted to be an oceanographer. Everything I did, from going on my first real research cruise in high school on the R/V Connecticut to studying Marine Science Physics at the University of San Diego to getting my mariners license at the Maine Maritime Academy, eventually landed me here. I worked for Scripps Institution of Oceanography as a shipboard tech, running the deck. I planned all the cruises, operated all of the oceanographic equipment and managed the computer systems on their smaller vessels. At Scripps, I met John Kemp, head of the WHOI mooring group, which eventually led to a job offer. The majority of the work I did for the WHOI mooring group was with OOI.

What is the most challenging part of your job? Balancing family and work has been my greatest challenge. Trying to rebalance that is part of the reason why I chose to change positions.

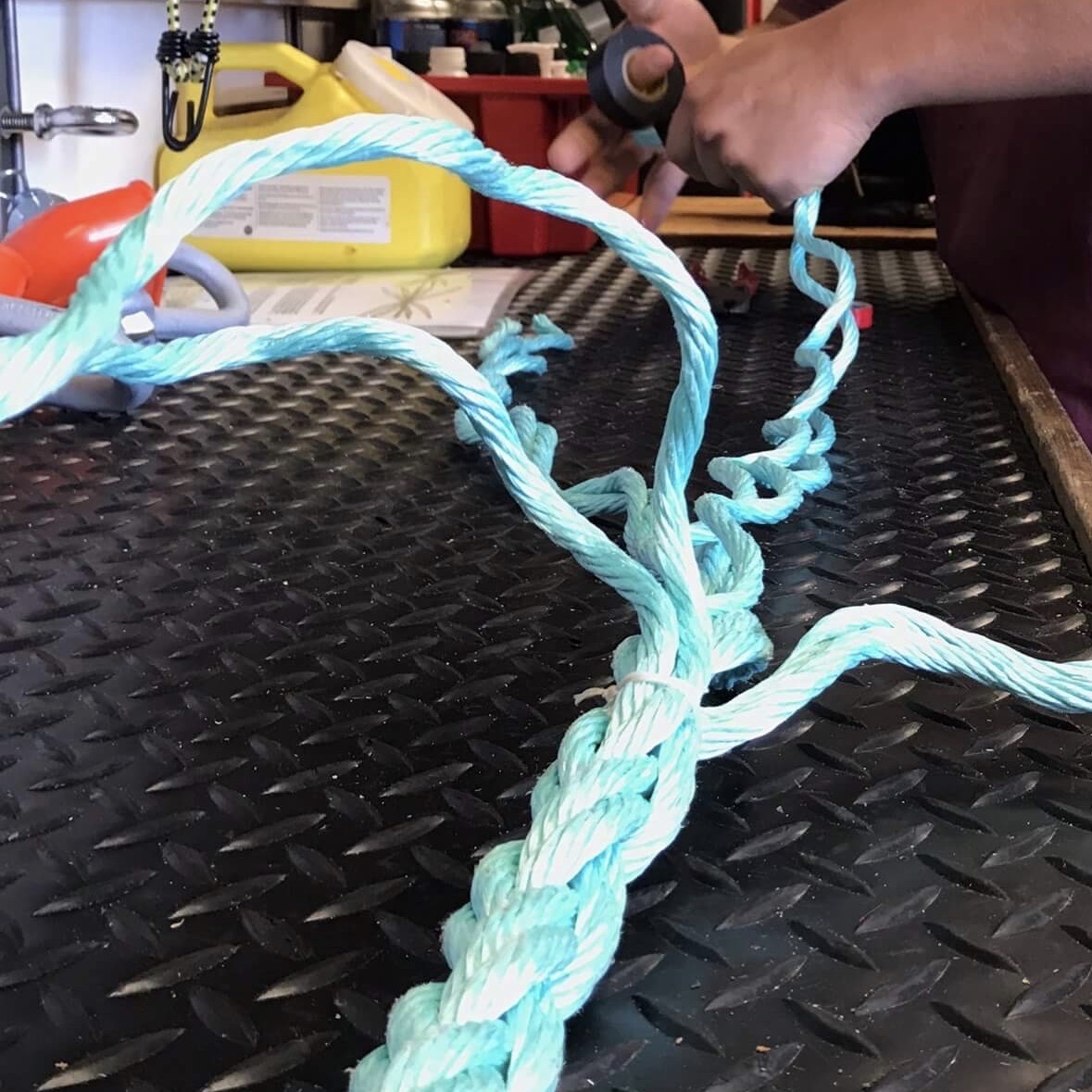

What do you enjoy most about your job? I like being able to teach the new techs and crew how to do the moorings. And I enjoy splicing—the act of weaving a piece of line together. It’s just relaxing. In addition to splicing line on the global moorings, I also splice the lines used for the Pioneer ARMS and profiler linepacks. I have made all of the ARMS linepacks with various helpers for the Pioneer cruises since the fall of 2014.

Kristin Politano

Faculty Research Assistant Kristin works with a team at Oregon State University on instrument quality control, refurbishment, and data monitoring. She also manages mooring integration for the Endurance Array, which involves building and integrating the electrical components of the moorings with the instrumentation.

How did you end up at OOI? In 2016, I joined the Oregon State University branch of PISCO (Partnership for the Interdisciplinary Studies of Coastal Oceans) as their lead mooring technician. That position allowed me to gain valuable experience with the process of building, integrating, deploying, and maintaining mooring systems. I participated in several OOI cruises while I was at PISCO and was able to meet the team of people who build and maintain the Endurance Array. When they eventually had an opening for a new position, I jumped at the chance to work with them full time.

What is the most challenging part of your job? Every new deployment brings its own set of challenges, but most of the big ones are time-related. We work closely with vendors and suppliers to stick to a timeline during builds, but it’s inevitable that delays in servicing or deliveries occur. When that happens, you have to be ready to move quickly when the parts eventually show up. Another big challenge is the lack of time to make significant improvements to the moorings. There are moments when we’re building the systems that we think “wouldn’t it be smarter it if we did it like this…” or “we could really make this more reliable if we changed that…” and often times the schedule doesn’t allow us the flexibility to make those changes.

What do you enjoy most about your job? I really enjoy problem solving, and in a lot of ways, the moorings are just like big puzzles. All the parts and pieces have to fit together perfectly for the system to function properly. Building the moorings in our shop and running them through integration and burn-in testing allows us to chase down and solve any issues that could mean the difference between a successful deployment, and a mooring that’s at sea for months with failed components. I like being able isolate and solve issues when they arise.

Jennifer Batryn

Engineer II

Jennifer works with (almost) all of the more than 1200 instruments that pass through the OOI program at WHOI. She is involved in the whole life cycle of the instruments, including testing, configuring, troubleshooting, deploying, data monitoring, and refurbishment.

How did you end up at OOI? I received my degree in mechanical engineering, thinking that I would end up in some sort of aeronautics or robotics field. I had never really considered a career centered around the ocean until taking part in a research program through my university. Through that program, we traveled to Malta for a month and collaborated with local archeologists, using small ROVs (remotely operated vehicles) and an AUV (autonomous underwater vehicle) to map out wells, cisterns, an underwater cave, and other features of interest around the island. Being able to work with interesting technology, travel and do field work, and collaborate with a multidisciplinary group really appealed to me, and I was sold on ocean research after that. I got involved with any ocean-based work I could afterwards, including internships at UC San Diego, National Geographic, and a summer fellowship at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. After college, I was thrilled to find my way back to WHOI, where I joined the OOI team.

What is the most challenging part of your position? Schedules and lack of time are the most challenging parts. Depending on how our cruise schedule line up for a particular year, it can be a surprisingly tight turnaround between recovering a set of moorings and when we need to make everything ready to deploy again. Inevitably, we have sensors and other components that come back from sea damaged. We then run into schedule conflicts with vendors and suppliers, and later discover instrument communication or sampling issues during our burn-in/testing period that need troubleshooting. The ship is going to sail regardless, which leaves very limited flexibility with timing, and sometimes there’s a real crunch period leading up to a deployment. It can also be very challenging to ensure we get good data for the entire duration of any particular deployment. The ocean is a tough environment for electronics and sensors, especially when in the water for prolonged periods. We run into problems with biofouling, physical damage from severe storms, icing, waves, or vibrations, and limitations of battery life, reagent, and other consumables.

What do you enjoy most about your job? Going to sea to support deployments and recoveries of our moorings is a nice change of pace from working in the lab and is very rewarding (if not exhausting). It’s great to see all of the work building up and burning-in of the mooring to that final end product of deployment in the ocean for six months to a year. It’s also great seeing all the data successfully come through back to shore. Long, tiring days at sea are offset by seeing all the wildlife and other natural sights in the open ocean (starry nights with no light pollution, Northern lights, stormy seas, icebergs, etc.), and traveling to different ports and experiencing different parts of the world. My dog (Teddy) was actually a Chilean street dog that I met while down in Punta Arenas preparing a mooring before a cruise. I ended up falling in love and bringing him back home with me after the cruise. Hard to beat that! It also has been really rewarding to see more people actually using OOI data, knowing that the work we are putting in is going towards the creation of a really unique, long-term data set.

Anything else you’d like to add? Going to school in such a male dominated field, it has been neat to find a core group of really smart and talented women within OOI. Everyone comes from such diverse backgrounds, and yet we all found our way to this project. Naturally the whole team is great though. It is equal parts entertaining and inspiring to work alongside everyone on our team, whether in the lab, on deck deploying a mooring, or scraping barnacles after a recovery.

Photo Credits from top

Diana Wickman headshot and glider Photo: Diana Wickman©WHOI for both

Trina Litchendorf securing oceanographic instruments on the Science Pod platform prior to a cruise. Photo: Dana Manalang

Meghan Donohue Photo: ©WHOI

Kristin Politano Photo: OSU

Jennifer Batryn in the freezer of the R/V Armstrong working on instrument calibrations at a controlled (cold) temp during the Pioneer 16 operation and maintenance cruise. Photo: Rebecca Travis©WHOI

Read MoreOOI Welcomes Data Discussions for NSF OED Synthesis Center Solicitation

The National Science Foundation recently issued a solicitation to create a Center for Advancement & Synthesis of Open Environmental Data & Sciences (NSF 21-549). The Center will be fueled by open and freely available environmental data, such as that provided by the Ocean Observatories Initiative (OOI), National Ecological Observatory Network (NEON), the Long-Term Ecological Research Network (LTER) network, and others.

The vision is that large, publicly accessible datasets will catalyze novel scientific questions in environmental biology and speed discovery through collaborations with scientists in other related disciplines. It is also hoped that the Center will help democratize science and diversify the STEM workforce by catalyzing the use of the open data by everyone, from collaborative teams to individual students, researchers, educators, fishers, and policy makers.

OOI is pleased to have been listed as a data source for the Center and looks forward to helping to generate answers to important environmental questions. For those considering submitting a proposal, OOI stands ready to help you learn more about OOI data. If you are interested in having such a discussion, please reach out directly to John Trowbridge.

Read MoreCelebrating OOI Women for International Women’s Day

March 8 is International Women’s Day. To celebrate the contribution of the many wonderful women in the OOI community, we share the stories of scientists Sophie Clayton, Hilary Palevsky, and Hilde Oliver. While their paths are different, their research interests varied, separately and together these three women are inspirational, as are the many other women who make up the OOI community.

Because it takes a village, we asked each of these women to share information about mentors who have helped them on their paths. These stories and the role of mentorship are intertwined in the profiles below in recognition of the women – and men – who have opened doorways for the next generation of scientists.

Read More