Posts Tagged ‘Biofouling’

Biofouling Preventatives on Surface Mooring Instrumentation

During the first leg of Pioneer 21, the team recovered the three surface moorings deployed in the Mid-Atlantic Bight (MAB) region, including the associated Multi-Function Nodes (MFNs) and Near-Surface Instrument Frames (NSIFs). Upon recovery, the state of the instrumentation at these sites showcased the effectiveness of biofouling mitigation strategies employed during this past year long deployment in the MAB region.

Biofouling — the accumulation of marine organisms such as algae, barnacles, and tube worms — is a challenge for sustained ocean observations. Unchecked growth can obstruct sensor faces, degrade data quality, and damage equipment. While complete prevention is rarely possible over extended deployments, targeted mitigation techniques can significantly limit biological overgrowth on critical sensing surfaces.

The following examples illustrate both the extent of biofouling on non-critical surfaces and the relative success of antifouling methods used to protect sensor interfaces:

[caption id="attachment_36259" align="alignnone" width="640"] The seven white wavelength band sensing points of the Spectral Irradiance sensor (https://oceanobservatories.org/instrument-class/spkir/) in this image had been kept free from biofouling by a neighboring UV light that had been carefully positioned to illuminate the sensing region during throughout deployment. (c): Sawyer Newman, WHOI[/caption]

[caption id="attachment_36260" align="alignnone" width="640"]

The seven white wavelength band sensing points of the Spectral Irradiance sensor (https://oceanobservatories.org/instrument-class/spkir/) in this image had been kept free from biofouling by a neighboring UV light that had been carefully positioned to illuminate the sensing region during throughout deployment. (c): Sawyer Newman, WHOI[/caption]

[caption id="attachment_36260" align="alignnone" width="640"] This photo shows a Fluorometer (FLORT) (https://oceanobservatories.org/instrument-class/fluor/) mounted to the SOSM-1 MFN used for turbidity sensing. This sensor face was kept clear from fouling by a rotating wiper. In contrast, tube worm growth is visible on non-sensing portions of the FLORT and adjacent structural elements of the MFN. (c): Sawyer Newman, WHOI[/caption]

[caption id="attachment_36261" align="alignnone" width="360"]

This photo shows a Fluorometer (FLORT) (https://oceanobservatories.org/instrument-class/fluor/) mounted to the SOSM-1 MFN used for turbidity sensing. This sensor face was kept clear from fouling by a rotating wiper. In contrast, tube worm growth is visible on non-sensing portions of the FLORT and adjacent structural elements of the MFN. (c): Sawyer Newman, WHOI[/caption]

[caption id="attachment_36261" align="alignnone" width="360"] Zinc oxide cream (specifically, commercial diaper rash cream) was applied to the sensor faces of ZPLSCs (https://oceanobservatories.org/instrument-class/zpls/) prior to deployment. This image shows tube worm growth on the non-sensing parts of the ZPLSC, while the round sensing area, coated with zinc oxide, remained clear of biological growth. (c): Sawyer Newman, WHOI[/caption]

Zinc oxide cream (specifically, commercial diaper rash cream) was applied to the sensor faces of ZPLSCs (https://oceanobservatories.org/instrument-class/zpls/) prior to deployment. This image shows tube worm growth on the non-sensing parts of the ZPLSC, while the round sensing area, coated with zinc oxide, remained clear of biological growth. (c): Sawyer Newman, WHOI[/caption]

These observations underscore the importance of selecting and applying biofouling prevention strategies tailored to each sensor’s operational context and sensitivity. The recovery and evaluation of these assets offer critical feedback for ongoing sensor maintenance and instrument integration modifications.

Read MoreShedding Light on Wave Energy Harvesting

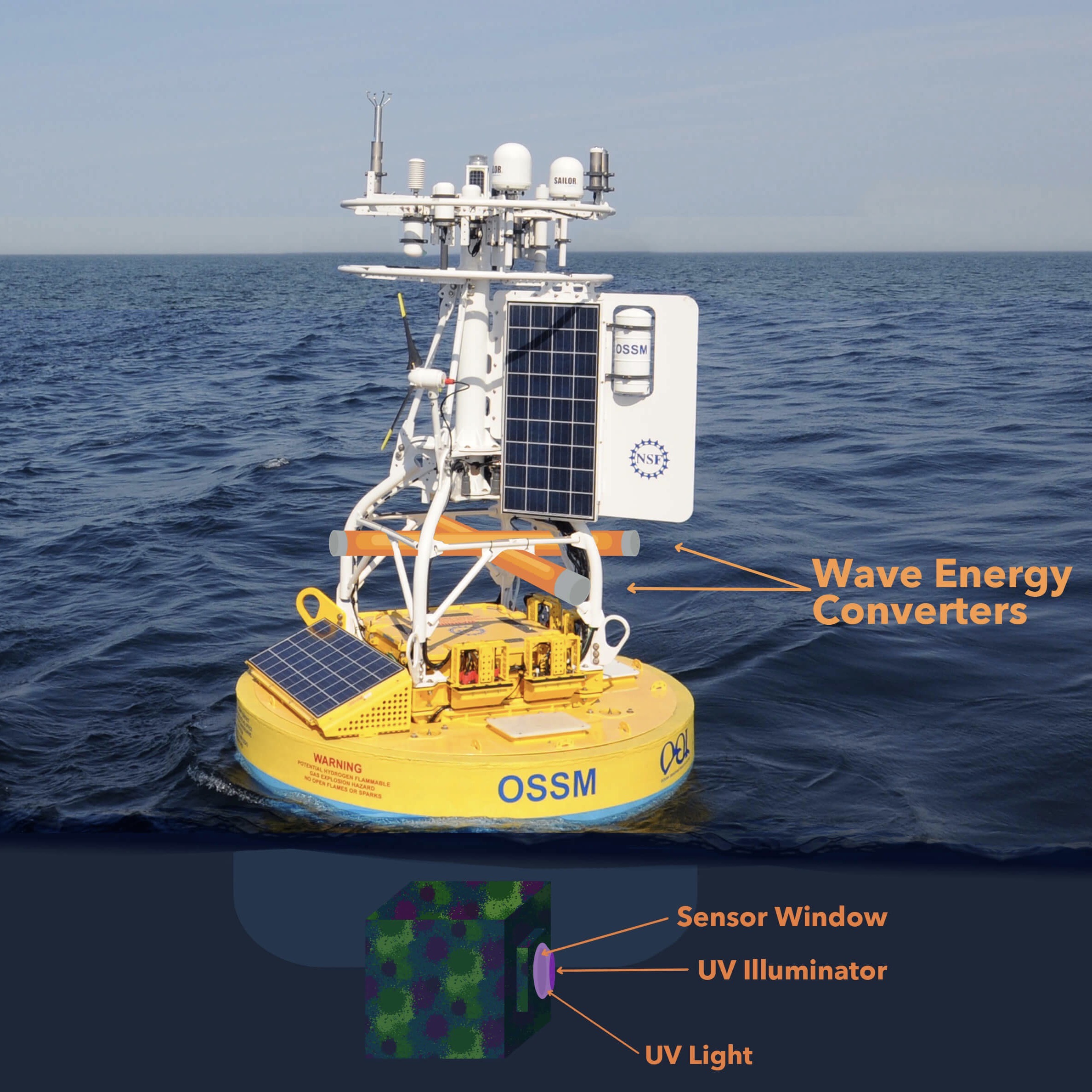

Two entrepreneurs and two engineers recently teamed up to develop a wave-based energy generator with the potential of powering the Pioneer Array, while also providing energy to a new, longer lasting, and potentially more effective way to keep the array’s sensors free and clear.

The Department of Energy thought the idea had such potential that it awarded the team a Small Business Technology Transfer (STTR) grant that will allow them to develop a proof of concept of this system by late March 2021.

The development team consists of grant Co-Investigator Matt Palanza, program engineer for the Ocean Observatories Initiative (OOI) at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI), Megan Carroll, a research engineer at WHOI and expert in the dynamics of moored systems, and Principle Investigator Julie Fouquet and Co-Investigator Milan Minsky, principals of 3newable, LLC, a firm dedicated to the development of small-scale wave energy converters. Fouquet started by developing and testing wave energy converter concepts on land, to choose an efficient, low-cost and flexible approach. Minsky brings to the team extensive experience in developing first-generation ultraviolet LEDs for medical and industrial applications that she will put to good use in designing a system to tackle serious biofouling conditions that plague all equipment put into the ocean for extended periods.

“The concept of harnessing wave energy at the Pioneer Array, then powering an ultraviolet LED anti-fouling light, which could possibly keep the array functioning much longer, would be a win-win. If this combination is proven here, it could have widespread application in oceanographic research and aquaculture applications, with tremendous potential for cost savings,” said Palanza.

Striving for Good Environmental Outcomes

Striving for Good Environmental Outcomes

Julie Fouquet founded 3newable LLC in 2015 with the goal of capturing electrical power from water waves as a source of renewable power. Previously, companies wanting to commercialize wave energy generation had failed while attempting to build utility scale systems, which were extremely costly. Years of experience in the semiconductor industry taught Fouquet that product development requires multiple design-build-test-redesign cycles. Companies developing utility-scale systems ran out of money before reaching a viable product. She chose to focus her efforts on developing an efficient and cost-effective small-scale wave energy converter that could fit into the back of an SUV and on a runabout boat.

Having worked together for decades, she and Minsky – now vice president of product at 3newable – teamed up to find out what sort of applications in the oceanographic community could use a small-scale wave energy converter.

After many meetings, they concluded that the Pioneer Array buoys would be a good testing ground. Palanza agreed and the team set out to write a proposal that would capitalize on their collective talents to provide a potential real-world application of wave energy and anti-biofouling technology.

The Pioneer Array buoys are already powered by wind and solar, but the wave energy converter offers a way to keep the sensors clear and recording for longer time periods using UV LED lights, possibly extending trip intervals needed to service the arrays.

Like most things in spring 2020, COVID caused delays in the launch of this project. DOE announced the award in May, but the actual award was delayed until early August, which potentially squeezes the March deadline for producing the feasibility study. From there, the team hopes to move forward to Phase 2, which would involve construction of both the wave energy conversion and UV anti-fouling prototypes and testing in the field.

“We are already working in a distributed way with processes in place so COVID hasn’t impacted our progress in analyzing data and developing lab tests,“ said Minsky. “But the interesting thing about the pandemic is that it has really propelled the UV LED field along as people explore its potential medical uses. Prices are dropping and quality is going up so we will be able to take advantage of these advances as we go about commercializing this module.”

During Phase 1, the team will be striving to answer the following questions:

· How much power is needed to run UV anti-biofouling equipment at the array?

· Can enough power be generated to meet the demand?

· How big of a wave energy converter unit will be needed?

· What are the unit size limitations if attached to the array?

“We all are excited to get this project launched. There’s a real need for improved anti-biofouling technology, and with the emergence of UV LEDs powered by waves onsite, it’s a sound solution with a potentially positive environmental impact, “added Palanza.

Read More

UV Anti-fouling Light Keeps Oxygen Sensors Clean

Biofouling is a real challenge to keeping equipment deployed in the ocean free functioning properly to deliver data to shore. The addition of UV light is helping to keep the oxygen optode sensors clear and recording data. Photo: Jon Fram, Oregon State University.[/caption]

Biofouling is a real challenge to keeping equipment deployed in the ocean free functioning properly to deliver data to shore. The addition of UV light is helping to keep the oxygen optode sensors clear and recording data. Photo: Jon Fram, Oregon State University.[/caption]

Biofouling is a hazard of keeping equipment in the ocean for long periods of time, particularly when it is near the surface where photosynthesis occurs. For OOI’s arrays that remain in the water for six months or longer, this is a pressing issue because of the need to ensure sensors can continue to collect and transmit data back to shore. The OOI scientists and engineers are always investigating ways to keep biofouling at bay. They recently worked with Aanderaa, which provides OOI’s oxygen optode sensors, to implement a solution to keep oxygen sensors free of biofouling by installing ultra-violet (UV) lights that periodically shine on the instruments’ sensing foil.

As early as 2016, a team of OOI engineers and technicians from Oregon State University, the University of Washington, and Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution began to tackle some of problems with the instruments selected by OOI and to improve the quality of instrument measurements. In October of 2016 AML Oceanographic showed OOI’s instrument group data from Ocean Networks Canada of a UV light used to mitigate biofouling on Aanderaa’s oxygen optodes. The following October, OOI deployed a side-by-side test of two oxygen optodes (one with a UV light pointed at it) at seven meters depth on the Oregon Shelf Surface Mooring. Data from the two sensors tracked each other for six weeks, and then the unprotected sensor fouled. Within weeks, there were daily afternoon spikes of up to twice the oxygen level of the protected sensor, with slightly lower measurements than the unprotected sensor at night due to respiration of the biofilm. The team found that the biofouling signal wasn’t always as dramatic, nor did it always develop in the same period of time after deployment. Physics has a hand in this, too. Sometimes the fouling signal disappeared after a storm cleaned off the sensor.

In summer 2018, OOI started deploying UV-protected oxygen optodes mounted shallower than 70 meters on Surface Moorings. By mid-209, once some initial hardware and deployment issues were resolved, OOI expanded deployment of UV-antifouling from moored dissolved oxygen sensors, to the dissolved oxygen sensors on the Coastal Surface Piercing Profilers, and then to uncabled digital still cameras moored at less than 70 meters depth.

Following the success of the UV-light test on dissolved oxygen sensors, UV antifouling was tested on a moored Pioneer Array spectral irradiance (SPKIR) sensor in 2018. Here too, the testing conducted with Sea Bird Scientific, the SPKIR vendor, confirmed that the UV light did not damage the instrument’s optics. As a result, in 2019, all subsurface OOI spectral irradiance sensors on Surface Moorings were outfitted with UV-antifouling mitigation, as well as the Coastal Surface Piercing Profilers and uncabled digital still cameras moored at less than 70 meters. The team has adjusted the cycle of the UV lights so that they prevent biofouling without damaging the sensors, interfering with measurements, or utilizing too much power.

“While the solution appears simple, it was a long journey to find the right mix of equipment and duration of use to resolve the issue of biofouling for each sensor at each location, “explained Jonathan Fram, project manager for the Coastal Endurance Array at Oregon State University. “An ongoing challenge is the intermittency of biofouling and the many forms it can take, which can make it difficult to properly diagnose the problem. Usually biofouling is a slimy film, but sometimes it can be a barnacle or another large creature.”

“The use of UV-lights for biofouling mitigation, although well-known, cannot often be used due to the power required,“ added Sheri White, senior engineer at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, who was instrumental in moving this solution forward on the Pioneer Array. “We have the advantage of generating our own power, so that we are able to implement it on a number of optical instruments on our Surface Moorings.”

OOI continues to measure the impact of the UV light on biofouling. While the results are clear that the UV lights increase measurement reliability and accuracy, the team is still trying to gauge the extent of the improvements. Data are annotated to indicate when UV-antifouling was used for each instrument deployment.

Read More