Posts Tagged ‘Global Irminger Sea Array’

Mission Accomplished Despite High Seas, Strong Winds

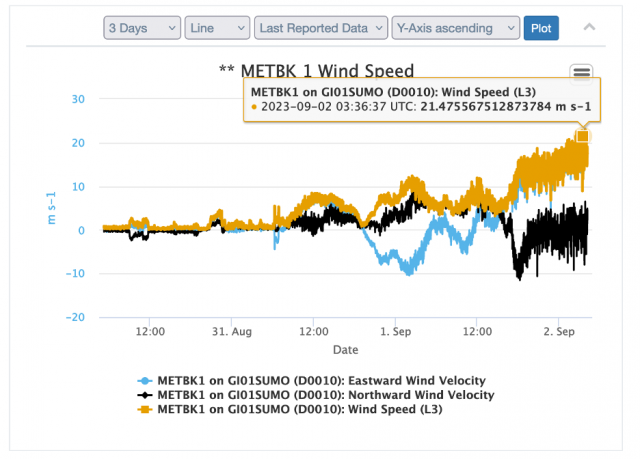

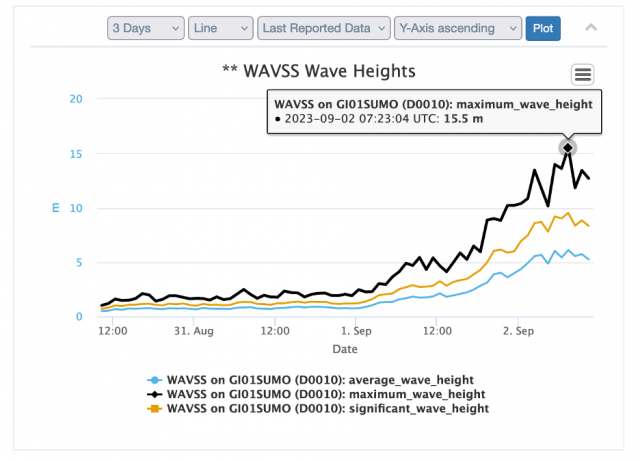

The Irminger 10 Recovery and Deployment Expedition had to keep a close eye on weather conditions. After arriving at the Irminger Sea Array site aboard the R/V Neil Armstrong, the ship was forced to take shelter in Prince Christian Sound off Greenland for two days to avoid 21.5 m/s (42 knot) winds and waves measuring more than 15.5 meters high (50 feet) as measured by the OOI Surface buoy (SUMO-10) meteorological systems.

[media-caption path="https://oceanobservatories.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/Screenshot-2023-09-07-at-10.18.07-AM.png" link="#"]On September 1, the R/V Neil Armstrong took refuge in Prince Christian Sound to avoid high winds and heavy seas that prevented safe deployment and recovery of the OOI moorings. The weather forecast called for 70 knot wind gusts and 30-foot waves at the work site![/media-caption]The team returned to the site once conditions settled down enough to work safely. The team monitored the weather carefully planning operations that fit the varying conditions and were able to squeeze out enough safe, workable days to accomplish the cruise’s primary objectives, and then some.

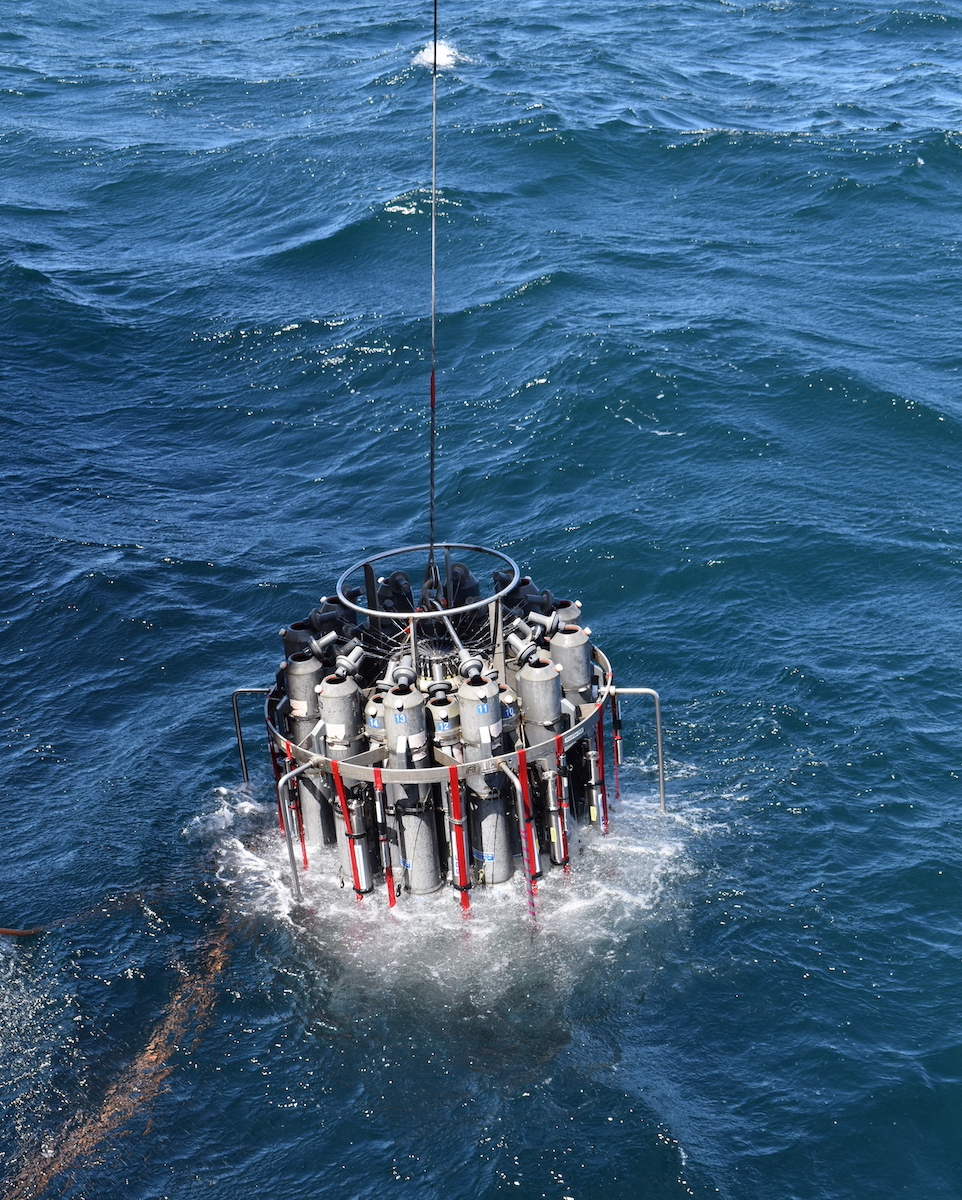

[media-caption path="https://oceanobservatories.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/global-surface-mooring.jpg" link="#"]The recovered global surface mooring was successfully brought onboard, secured, and ready for the long trip home. Credit: John Lund © WHOI.[/media-caption]The ship departed the Irminger Array on September 12th and headed for the last CTD (Conductivity, Temperature, and Depth) measurement at OSNAP Station M4 on the way home to Woods Hole, MA, which completed the cruise objectives. Despite the obstacles posed by conditions in this windy and wild part of the norther Atlantic, four moorings were deployed and recovered. Two open ocean gliders and one global profiling glider were deployed. CTD casts for instrument cross calibration were made during each deployment/recovery. Meteorological surveys were conducted and ancillary CTD casts to support the OSNAP program were made. In addition, a significant number of marine mammal sightings were recorded.

Conditions didn’t cooperate as the team headed home. The Captain of the Armstrong had to carefully pick a transit to avoid Hurricanes Lee and Margot turning up the Atlantic.

Said Chief Scientist John Lund, “The success of this cruise is a result of the tremendous teamwork from the Armstrong crew, shoreside support, and the OOI and CRL engineers and technicians who prepared and deployed the Irminger-10 assets. Their hard work has made possible the data that will be sent home for the next year.”

The ship and its hard-working team are expected to arrive back at the Woods Hole dock on September 21. More details about the expedition and images and video are available here.

Read More

Tenth Refresh of the Irminger Sea Array

On August 27th, a team of 13 scientists and engineers boarded the R/V Neil Armstrong in Reykjavik, Iceland to head to the Irminger Sea Array. Most of the array’s infrastructure and instrumentation was shipped from Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI) in mid-July to Iceland, where it arrived in mid-August. Part of the scientific party traveled to Reykjavik in mid-August to reassemble the moorings and conduct a “burn-in,” a test period for the power, data, telemetry, and instrument systems to ensure everything is operational prior to loading the vessel.

The Irminger Sea Array is in a region with high wind and large surface waves in the North Atlantic and is one of the few places on Earth with deep-water formation that feeds the large-scale thermohaline circulation. Data collected by the Irminger Sea Array are providing critical insights into circulation patterns, ocean processes, and possible climate-induced changes occurring in this important oceanic area.

After an ~ two-day transit (550 nautical miles) to the array site off the tip of Greenland, the team will recover and deploy four moorings and three gliders over the next two and a half weeks. They will conduct CTD (conductivity, temperature, and depth) casts at the deployment/recovery sites and carry out shipboard sampling for field validation of the platforms and sensors that will remain in the water for the next year.

In addition to the recovery and deployment operations, the team will be conducting some CTD calibration casts in support of OSNAP-GDWBC (Overturning in the Subpolar North Atlantic Program-Greenland Deep Western Boundary Current). A participant from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration will also be on board using “Big Eye” binoculars mounted on a forward deck to make observations of marine mammals during the transit and in the Irminger Sea.

[media-caption path="https://oceanobservatories.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/Big-eyes.jpg" link="#"]Large, deck-mounted binoculars known as “big eyes” are used for marine mammal observations. NOAA Research Wildlife Biologist Peter Duley will be aboard the R/V Neil Armstrong watching for marine life in the Irminger Sea. Credit: Al Plueddemann ©WHOI.[/media-caption]The Irminger Team will also be testing out some equipment modifications on this deployment. One change is an updated satellite telemetry system. This system would provide higher bandwidth allowing better and quicker data transmission from the global surface mooring potentially saving power, and better remote command and control of the mooring systems. Another change is a revised mounting scheme for the glider optode, which measures dissolved oxygen concentrations in the water column. The new mount may provide better in-air measurements during glider surfacing. The in-air measurements allow scientists to characterize the changing accuracy of the instrument over time.

“It’s always a challenge to get ready for this month-long expedition to this remote, but critical region, but we are ready and eager to get there,” said John Lund, Chief Scientist for Irminger 10. “We are pleased to play a part in collecting data that scientists are using to better understand changes occurring in this region, with implications for both weather and climate.”

The team will reporting regular updates from the field. Bookmark this page so you can follow along on their progress.

Read MoreDrivers of Ocean Overturning Circulation Revealed

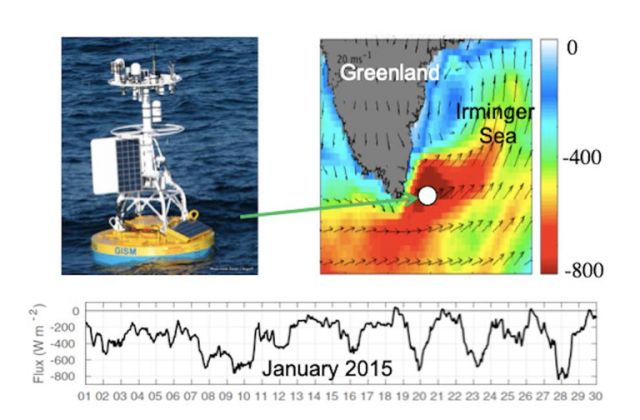

rminger Surface Mooring data were used to identify a new mechanism by which the atmosphere controls ocean heat loss leading to dense water formation. The results are particularly important as the connection between air-sea exchanges and the ocean circulation is still poorly understood, hindering attempts to understand the climate change induced slowdown of the Atlantic circulation.

Read MoreCadet Reports on First Voyage on a Research Vessel

Massachusetts Maritime Academy First-Class Cadet, Ella Strano, recently returned from two months aboard the R/V Neil Armstrong. Ella participated as a working crew member for the recovery and deployment of OOI’s Global Irminger Sea Array in July, followed by deployment of moorings and sampling equipment for the Overturning in Subpolar Arctic Project (OSNAP). She had a few days in shore in Reykjavik, Iceland, as the science parties and equipment were swapped out and onboard.

In a word, Ella described her experience as “Awesome!” and one that was a very different experience than that of her peers’ summer internships shipboard experiences. The majority of cadets at the Massachusetts Maritime Academy shipped out on cargo vessels and bulk carrier tugs for their first experiences of life at sea.

Being one of a few stationed on research vessels presented both opportunities and challenges.

“I definitely had to go with the flow,” she explained. “But l had the opportunity to learn not only from the crew, but from the scientists on board.” Ella’s minor is marine biology so she enjoyed the science aspects of the expedition, even though her responsibilities were primarily with helping to keep the ship operational so the science could be conducted.

Part of MA Maritime’s mission is to provide their students with hands-on at-sea experience so they understand the language and culture of shipboard life. In meeting the spirit of the experience, Ella did almost everything aboard the ship while she was a mate on the Armstrong. During the Irminger expedition, her duties were mostly on deck. She worked with the mooring team and observed how deployment and recovery operations could be conducted safely and successfully. Ella joked that she also did her fair share of cleaning the ship during her first month at sea.

[media-caption path="/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/Working-Aframe-2-scaled.jpg" link="#"]Ella Strano operating the Aframe used to recover and deploy OOI moorings. [/media-caption]During her second stint for the OSNAP expedition, her duties turned more inward and included work in the engine room, on the bridge, and even helped maneuver the ship to stay on station—a critical task for any science operation at sea. She had her hand in everything on the ship, except for the galley, which was left to the professionals.

Ella also experienced a fair share of weather during her initial trip to the North Atlantic, but was pleased that in spite of some low-pressure and high wind days, the ship never had to abandon its mission to find shelter from the weather.

After two months at sea, Ella said it affirmed what she’s interested in doing after graduating next year. After disembarking from the Armstrong, she said, “I love this. It’s so cool that people get to go out to sea and be involved with science, but not necessarily specialize in one area of science.” She sees life aboard a research vessel as offering her the opportunity to be involved with many different science initiatives, learn what’s going on, and never get bored.

Ella said there seems to be an uptick of interest in working aboard science research vessels as she was one of seven of her classmates who sought such a placement, and only three succeeded. If this holds true that would be good news for research ships, which often have to compete for staff who have the potential to earn more working aboard commercial vessels.

Ella’s experience offered something of greater value to her. “There was a really good camaraderie between the science group and the officers,” she explained. “We were all working together and share experiences during mealtimes and cheese-30 every day”. (A spread of cheese and meats is provided every day at three o’clock aboard the Armstrong as a break and snack). “The crew really tried to make life pleasant aboard the ship, which was great because we were at sea for a long time.”

[media-caption path="/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/ella-on-bridge.png" link="#"]Ella Strano on the bridge of the R/V Neil Armstrong. [/media-caption]If all goes as planned, Ella will graduate next year with a Bachelor of Science Degree in Marine Transportation from MA Maritime and with an enlisted unlimited tonnage, third officer certificate from the U.S. Coast Guard. She hopes to find a place aboard the Armstrong or other science-related position, inspired by a full female bridge team, and science party comprised of 50 percent women, and led by a female chief scientist, all of whom showed her what is possible.

Read More

Despite Weather, Irminger 9 Met Objectives

The R/V Neil Armstrong departed Woods Hole, Mass., on June 20. Under the direction of Chief Scientist Sheri N. White of Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI), the 14-member science party headed to OOI’s Global Irminger Sea Array for the ninth time to recover and deploy moorings and gliders and carry out scientific sampling. Nearly a month later, the ship and science party pulled into the port of Reykjavik, Iceland, on July 16th, having accomplished all of its objectives.

“The Irminger Sea can be a challenging environment to work in. Storms with high winds and seas regularly move through the area, and these conditions can limit our mooring recovery and deployment operations,” said Chief Scientist Sheri N. White. “We were lucky to have relatively good weather conditions during our cruise, and adjusted our schedule when needed when storms passed through. Thanks to an excellent team – the ship’s crew and shipboard science technicians, the mooring operations team, and OOI and OSNAP teams – we able to accomplish all of our goals. My huge thanks to everyone on the ship and all of our shore-side support for all of their efforts.”

In addition to ten OOI personnel, the team was rounded out by three members from OSNAP (Overturning in the Subpolar North Atlantic Program) and a marine mammal observer from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

For OOI, the team successfully recovered and deployed a Surface Mooring, Hybrid Profiler Mooring, and two Flanking Moorings, and deployed two new Irminger Sea gliders. For OSNAP, the team recovered and deployed four new moorings, replacing those originally deployed in the Summer 2020. The team also conducted CTD casts with salinity, oxygen, carbon, nutrient and chlorophyll water sampling. These sampling measurements are used for instrument validation and to further characterize the region of the moored array.

Why the Irminger Sea?

The Global Irminger Sea Array is off the southeast tip of Greenland, close to 39°W, 60°N. Data from this location are improving understanding of the impact of natural and climate variability in the region. The location experiences strong air-sea interaction and wintertime water mass formation that supports the global thermohaline (a.k.a. meridional overturning circulation – MOC). In recent years, a freshening of the water column has been observed.

The combination of the moored array and the gliders in the Irminger Sea enables investigation into the role of ocean processes at mesoscale and sub-mesoscale horizontal length scales through observations that sample the full water column, from the sea floor to the sea surface. The Surface Mooring provides a unique time-history of observations of surface meteorology and air-sea fluxes.

A Look at Life at Sea

The following and in the sidebar to the right is an assortment of activities onboard the Armstrong during the month of July. Other images and stories can be found here.

[media-caption path="/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/Pete_bow.jpeg" link="#"]Whale sightings: Marine mammal observer Peter Duley spent many hours on deck looking for marine mammals. He observed Humpback, Beaked, Sei, and Fin whales, as well as orcas, harbor porpoise and common dolphins. Credit: Sheri N. White © WHOI.[/media-caption] [media-caption path="/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/pilot-whales_sm-2048x1365-1.jpeg" link="#"]Pod came to visit: A pod of pilot whales on a foggy day in the Irminger Sea. Credit: Peter Duley, NOAA.[/media-caption] [media-caption path="/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/Glider_DSC_0381.jpeg" link="#"]Glider missions: Gliders have two missions at the Irminger Sea Array. They travel around the triangular array to collect data (temperature, salinity, fluorescence and dissolved oxygen) in between the moorings. And, they pass the data from the subsurface mooring to shore. When they come to the surface, they send their data and the subsurface mooring data back to shore via satellite. Credit: Sawyer Newman©WHOI.[/media-caption] Read MoreMeasurements Below the Surface

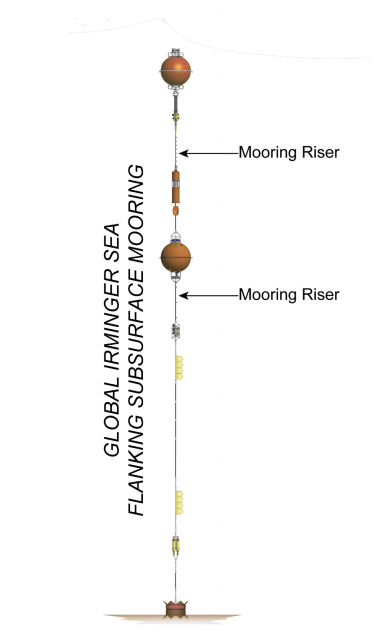

Strong winds and large waves in remote ocean locations don’t deter the Ocean Observatories Initiative (OOI) from collecting measurements in spite of such extreme conditions. By moving the moorings below the surface, the OOI is able to secure critically important observations at sites such as the Global Station Papa Array in the Gulf of Alaska, and the Global Irminger Sea Array, south of Greenland. These subsurface moorings avoid the wind and survive the waves, making it possible to collect data from remote ocean regions year-round, providing insights into these important hard-to-reach regions.

Instrumentation on the surface mooring in the Irminger Sea, however, has nowhere to hide and the measurements they provide are also often crucial for investigations, such as net heat flux estimates. Providing continuous information about wind and waves remains one of the most challenging aspects of OOI’s buoy deployments in the Irminger Sea. Fortunately, with each deployment, OOI is improving the survivability of the surface mooring so they continue to add to the valuable data collected in the region by their subsurface counterparts.

[media-caption path="/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/FLMB-9_DSC_0934.jpg" link="#"]The top sphere of a Flanking Mooring being deployed through the R/V Neil Armstrong’s A-Frame. Credit: Sawyer Newman©WHOI.[/media-caption]Below the surface in the Irminger Sea

A team of 15 OOI scientists and engineers spent the month of July in the Irminger Sea aboard the R/V Neil Armstrong, recovering and deploying three subsurface moorings there, along with other array components. The Irminger Sea is one of the windiest places in the global ocean and one of few places on Earth with deep-water formation that feeds the large-scale thermohaline circulation. Taking measurements in this area is critical to better understanding changes occurring in the ocean.

OOI’s Irminger Sea Array also provides data to an international sampling effort called OSNAP (Overturning in the Subpolar North Atlantic) that runs across the Labrador Sea (south of Greenland), to the Irminger and Iceland Basins, to the Rockall Trough, west of Wales. The OOI subsurface Flanking Moorings form a part of the OSNAP cross-basin mooring line with additional instruments in the lower water column. During this current expedition, the Irminger Team will be recovering and deploying OSNAP instruments that are included as part of the OOI Flanking moorings, in addition to turning several OSNAP moorings as well.

[media-caption path="/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/FLMB-9_DSC_0941.jpg" link="#"]The Flanking Mooring top float in the water during deployment. The sensors mounted in the sphere will measure conductivity, temperature, fluorescence, dissolved oxygen and pH at 30 m depth. Credit: Sawyer Newman©WHOI.[/media-caption]The triangular array of moorings in the Irminger Sea provide data that resolve horizontal variability, how much the physical aspects of the water (temperature, density, currents) and its chemical properties (salinity, pH, oxygen content) change over the distance between moorings. The individual moorings resolve vertical variability – the change in properties with depth. Three of these moorings are entirely underwater, with no buoy on the surface. They do have, however, multiple components that are buoyant to keep the moorings upright in the water column.

[media-caption path="/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/FLMB-9_DSC_0984.jpg" link="#"]The mid-water sphere holds an ADCP instrument which will measure a profile of water currents from 500 m depth to the sea surface. Photo Credit: Sawyer Newman©WHOI.[/media-caption]Each subsurface mooring has a top sphere at 30 m depth, a mid-water sphere at 500 m depth, and back-up buoyancy at the bottom to ensure that the mooring can be recovered if any of the other buoyant components fail. Instruments are mounted to the mooring wire to make measurements throughout the water column.

[media-caption path="/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/FLMB-9_IMG_5328.jpg" link="#"]Glass balls in protective “hard hats” provide extra flotation at the bottom of the mooring. Their tennis ball yellow color looks almost fluorescent in the brief (and much enjoyed) sunshine. Photo Credit: Sheri N. White©WHOI.[/media-caption] Read MoreMonth-long Expedition to Refresh Irminger Sea Array

In late June, a team of 15 scientists and engineers headed to the Irminger Sea, a region with high wind and large surface waves in the North Atlantic. This remote ocean region is one of the few places on Earth with deep-water formation that feeds the large-scale thermohaline circulation.

[media-caption path="/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/IMG_5251.jpg" link="#"]The R/V Neil Armstrong is loaded with Irminger Sea gear, ready to depart fo a month-long expedition to recover and deploy OOI’s Global Irminger Sea Array. Photo: Sheri N. White©WHOI.[/media-caption]

The Irminger Sea 9 expedition is taking place on the R/V Neil Armstrong, operated by the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI). After an eight-day transit to the mooring array site off the tip of Greenland, the team will recover and deploy four moorings and three gliders over the next two and a half weeks. They will conduct CTD (conductivity, temperature, and depth) casts at the deployment/recovery sites and carry out shipboard sampling for field validation of the platforms and sensors that will remain in the water for the next year.

In addition to the Ocean Observatories Initiative’s (OOI) operations, a team from OSNAP (Overturning in the Subpolar North Atlantic Program) also will be onboard to recover and deploy four moorings, conduct CTD casts and water sampling at the mooring sites, and conduct additional instrument field validation tests to ensure the quality of the data collected. A participant from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration will also be on board using Big Eyes binoculars mounted on a forward deck to make observations of marine mammals during the transit and in the Irminger Sea.

[media-caption path="/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/big_eyes.jpg" link="#"]Large, deck-mounted binoculars known as “big eyes” are used for marine mammal observations. NOAA Research Wildlife Biologist Peter Duley will be onboard the R/V Neil Armstrong watching for marine life in the Irminger Sea. Photo: Al Plueddemann ©WHOI.[/media-caption]

“Measurements in this remote ocean region are critical to increasing understanding of changes occurring in the ocean,” said Al Plueddemann, head of the OOI Coastal and Global Scale Nodes, which operates the OOI Global Irminger Sea Array. “It’s great to have a collaborative effort with OSNAP in this important area and an opportunity to learn more about marine life during this month-long expedition.”

Read MoreRemotely Fixing and Preventing Mooring Issues

Alex Franks’s job is a big one. He is charged with fixing various issues that occur on OOI moorings, while they are hundreds and sometimes even thousands of miles away in the ocean. As an Engineer II at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI), Franks is intimately familiar with the mooring system controller software, which allows him to troubleshoot and fix instrumentation problems on OOI moorings, regardless of their location.

Franks has been working with electronics for over a decade and solving OOI mooring-related challenges since 2015. Many examples exist of his innovative solutions. In 2020, for example, the satellite Internet service that was being used to send data from OOI moorings to WHOI servers was no longer a viable solution. The WHOI team faced the task of either finding a replacement system, or working with the then-current system. One easily implementable solution was to move to transmitting data through OOI’s Iridium radio antennas full time. There were downsides to this solution, however. It would allow no margin of error, would consume more power, and still not be able to send data from all the instruments.

Franks figured out a better solution that would both keep costs manageable and continue to meet timely data transmission goals by modifying the Iridium file transfer portion of the mooring software to accommodate a new data transfer scheme. The new scheme used a feature of the computer program rsync, a fast and versatile file copying tool, called “diff”. Instead of using rsync to communicate with shore servers and determine the “delta” or change between the new instrument data on the mooring and the instrument data files on the WHOI server, he used one of the mooring’s onboard computers as an intermediary server to generate “diff” files against (delineating old from new data). These files were then generated and stored, and sent over the Iridium connection. Using this new configuration, Franks succeeded in sending the entire dataset of all instruments on the mooring, except one that was sent at a reduced sample rate. While transmission times can vary with weather conditions, this newly configured system sends data to the server every 20 minutes every other hour, reducing transmission times from 1440 minutes per/day to about 240 minutes per day.

[media-caption path="/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/DSC_0639-copy.jpg" link="#"]Waves in the North Atlantic can get pretty large, which makes it hard to conduct research at sea, especially in winter. The waves and wind in the Irminger Sea also create challenges for ocean observing equipment in the water there year-round. Credit: ©WHOI.[/media-caption]

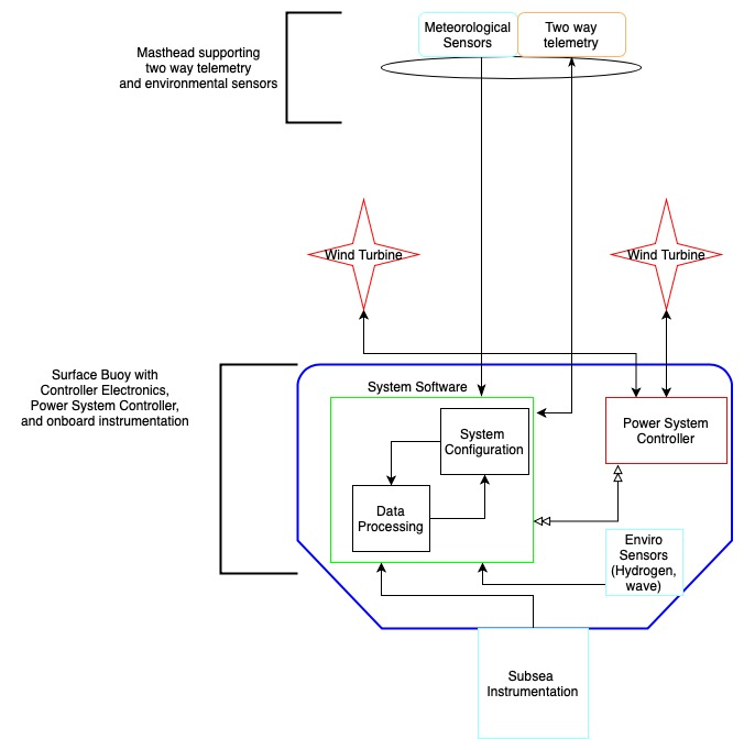

Franks also found ways to remotely manage mooring issues caused by weather and sea state by modifying software that controls wind turbines. Wind turbines play a critical role on OOI moorings, providing power to recharge the main system batteries. At the Irminger Sea Array, where the sun is absent for months at a time (the moorings also utilize solar panels), these wind turbines are critical. Prior to Franks’ software fix, human input was required to disable the turbines to prevent them from spinning while wave heights were too great. Franks modified the software used to control the spinning of the turbines to read environmental data from the buoy itself and make automated decisions in real-time that previously had to be done manually. The system now changes its configuration based on a variety of sensor inputs, which make for more immediate decisions to ensure the continued safe operations of the turbines. The software modifications not only help mitigate heavy sea damage to the turbines but saves power, as well. The software detects when the air temperature is above freezing and turns off the precipitation sensor heaters, conserving energy when possible. The software also has fail-safes in place for high or low voltage and to determine hydrogen concentration levels inside the electronics. An illustration of this software configuration is provided below.

[media-caption path="/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/Mooring-system-software-upgrade.png" link="#"] This new software configuration detects when the air temperature is above freezing and turns off the precipitation sensor heaters, and has fail-safes in place for high or low voltage and for hydrogen concentration levels inside the electronics .Credit: ©WHOI.[/media-caption]

Franks has also developed software improvements to the power system controller inside the OOI surface moorings. His work ran the gamut from disabling operational bugs in the system to reducing power consumption to fixing software errors to increase reliability. During a year-long deployment in the Irminger Sea, part of the power system controller board failed. Franks installed a software patch remotely that was able to limit the level of charge coming from wind turbines and wrote a fail-safe feature for the system to disconnect all charging sources if the voltage approached dangerous levels.

The challenges are what keeps Franks enthusiastic about his job, “I just love trying to figure out a solution and it’s particularly rewarding to be able to remotely resolve issues with equipment deployed in the open ocean.”

Read More

Atlantic Water Influence on Glacier Retreat

Adapted and condensed by OOI from Snow et al., 2021, doi:/10.1029/2020JC016509

The warming of Atlantic Water along Greenland’s southeast coast has been considered a potential driver of glacier retreat in recent decades. In particular, changes in Atlantic Water circulation may be related to periods of more rapid glacier retreat. Further investigation requires an understanding of the regional circulation. The nearshore East Greenland Coastal Current and the Irminger Current over the continental slope are relatively well studied, but their interactions with circulation further offshore are not clear, in part due to relatively sparse observations prior to establishing the OOI Irminger Sea Array and the Overturning in the Subpolar North Atlantic Program (OSNAP).

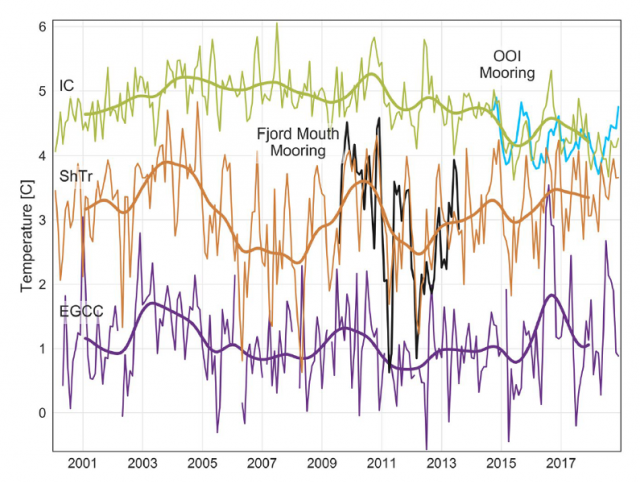

[media-caption path="/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/Pioneer-highlight.png" link="#"]Satellite-derived sea surface temperature after adjustment for the Irminger Current (IC; green), Shelf Trough (ShTr; orange), and East Greenland Coastal Current (EGCC; purple). Monthly values (thin lines) are shown for 2000-2018 with 24-month low-passed records overlain. In situ observations from the fjord mouth (290 m: Black) and OOI flanking mooring FLMA (180 m; blue) are shown for comparison.[/media-caption]

In a recent study (Snow et al., 2021) use in-situ mooring data to validate satellite SST records and then use the 19-year satellite record to investigate relationships between glacier melt and Atlantic Water variability. In order to use the satellite records for this purpose, several adjustments must be made, including accounting for cloud and sea ice contamination, eliminating seasonally-varying diurnal biases, and removing the influence of air temperature. This adjusted satellite SST can be compared to in-situ mooring data during a portion of the record. A coastal mooring near the Sermilik Fjord mouth and the OOI Irminger Sea Array provide useful records during 2009-2013 and 2014-2018, respectively (Figure 24). An interesting aspect is that the temperature record from OOI Flanking Mooring A (FLMA) is useful for this purpose even though the measurements are at 180 m depth. This is because the upper ocean is relatively homogeneous in this region, and the mixed layer is deeper than 180 m during much of the year. The authors find that the adjusted satellite SST is consistent with the in-situ records on monthly to interannual time scales (Figure above). This provided the motivation to investigate relationships between the 19 year satellite record and glacier discharge rates.

The study concludes that warmer upper ocean temperatures as far offshore as the OOI Irminger Sea Array were concurrent with increased glacier retreat in the early 2000s, in support of the idea that Atlantic Water circulation plays a role. However, they also note that this influence is not direct, because of substantial variation in how Atlantic Water is diluted as it flows across the shelf towards Sermilik Fjord. The idea that time-varying dilution of Atlantic Water governs the temperature of water reaching the glacier was not previously understood, and resolving such small-scale, time-varying processes is a challenge for models. The authors conclude that with appropriate adjustments, “[satellite] SSTs show promise in application to a wide range of polar oceanography and glaciology questions” and that the method can be generalized to other glacier outflow systems in southeast Greenland to complement relatively sparse in-situ records.

Snow, T., Straneo, F., Holte, J., Grigsby, S., Abdalati, W., & Scambos, T. (2021). More than skin deep: Sea surface temperature as a means of inferring Atlantic Water variability on the southeast Greenland continental shelf near Helheim Glacier. J. Geophys. Res: Oceans, 126, e2020JC016509. https://doi.org/10.1029/2020JC016509.

Read MoreImproving Remote System Response in Increasingly Hostile Oceans

Wind and Waves and Hydrogen, Oh My!

Improving remote system response in increasingly hostile oceans

This article is a continuation of a series about OOI Surface Moorings. In this article, OOI Integration Engineer Alexander Franks discusses the mooring software and details some of the challenges the buoy system controller code has been written to overcome.

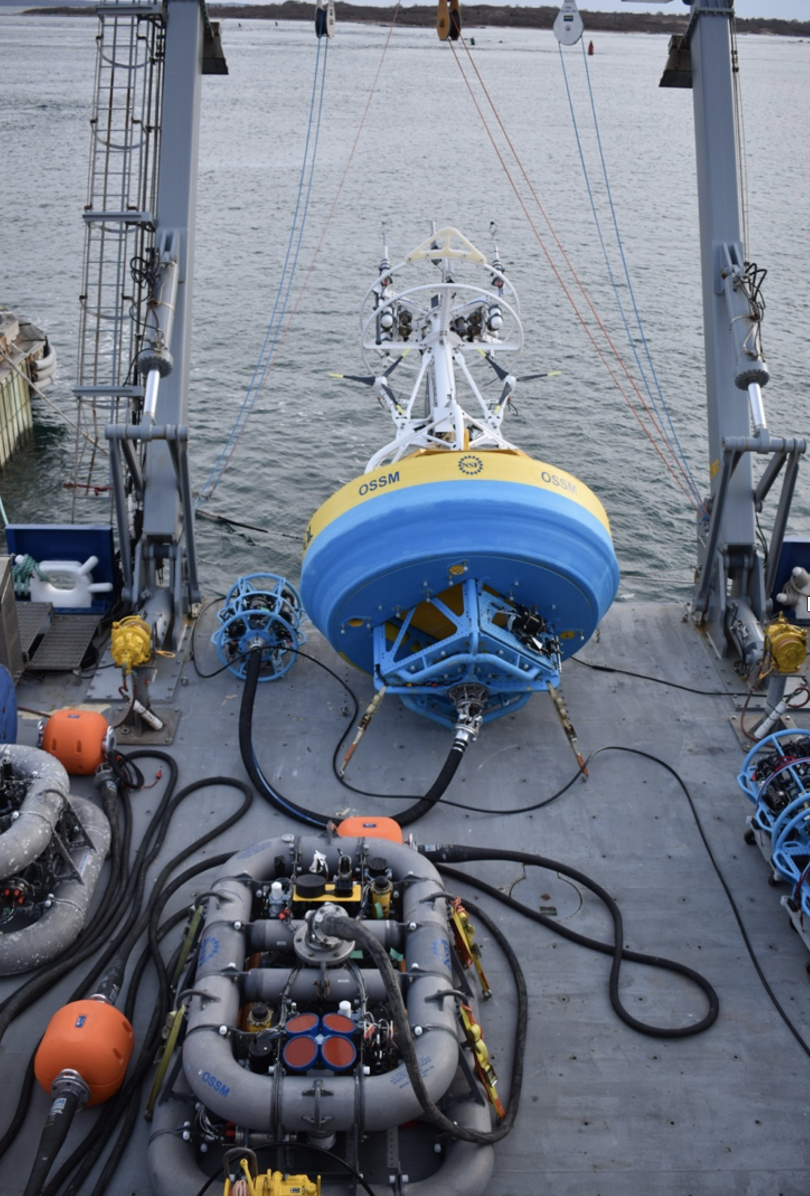

Components of the OOI buoys working in concert make up a system that is designed for deployment in some of the most challenging areas of our world’s oceans. These systems collect valuable scientific data and send it back to Wood Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI) servers in near real time. Mechanical riser pieces (wire rope, and/or stretch hoses) moor the buoy to the bottom of the ocean. Foam flotation keeps the buoy above water in even the worst 100-year storm, while its masthead supports instrumentation and satellite radios that make possible the continuous relaying of data. The software controlling the system is just as important as the physical aspects that keep the system operating.

The system software has a variety of responsibilities, including setting instrument configurations and logging data, executing power schedules for instruments and parts of the mooring electronics, controlling the telemetry system, interfacing with lower-level systems including the power system controller, and distributing GPS and timing. The telemetry system is a two-way communication path, so the software controls data delivery from the buoy, but also provides operators with the ability to perform remote command and control.

[caption id="attachment_22938" align="alignnone" width="745"] Software flow diagram created by OOI Integration Engineer Alex Franks[/caption]

Software flow diagram created by OOI Integration Engineer Alex Franks[/caption]

The unforgiving environment and long duration deployments of OOI moorings lead to occasional system issues that require intervention. Huge storms, for example, can build waves so high that they threaten wind turbines on the moorings. At the Irminger Sea Array, ice can accumulate so much as to drastically increase the weight of the masthead, and with subsequent buoy motion, risk dunking the masthead and instruments. Other mooring functions require constant attention. The charging system must be monitored to ensure system voltages stay at safe levels and hydrogen generation within the buoy itself is kept within safe limits. Two-way satellite communication allows operators to handle decision making from shore using the most up-to-date information from the buoy.

“Since starting in 2015 and following multiple mooring builds and deployments, I’ve realized that issues can rapidly arise at any time of the day or night. I started thinking about what the buoys can do for themselves, using the data being collected onboard,” Franks said.

One of the game-changing upgrades implemented by Franks was to read environmental data and make automated buoy safety decisions in real-time that were previously performed by the team manually. For example, previously, the team would need to monitor weather forecasts and decide preemptively whether changes to buoy operations were advisable. With recent software changes, the system can now change its configuration based on a variety of sensor inputs. These variables include system voltage, ambient temperature, hydrogen levels inside the buoy well, wind speed, and buoy motion (for sea state approximation). In addition to the software updates, the engineering team redesigned the power system controller. They added charge control circuits and the ability to stop the wind turbines from spinning. The software and electrical upgrades now provide redundant automated safeguards against overcharging situations, hydrogen generation, and turbine damage, maximizing buoy operability in harsh environments.

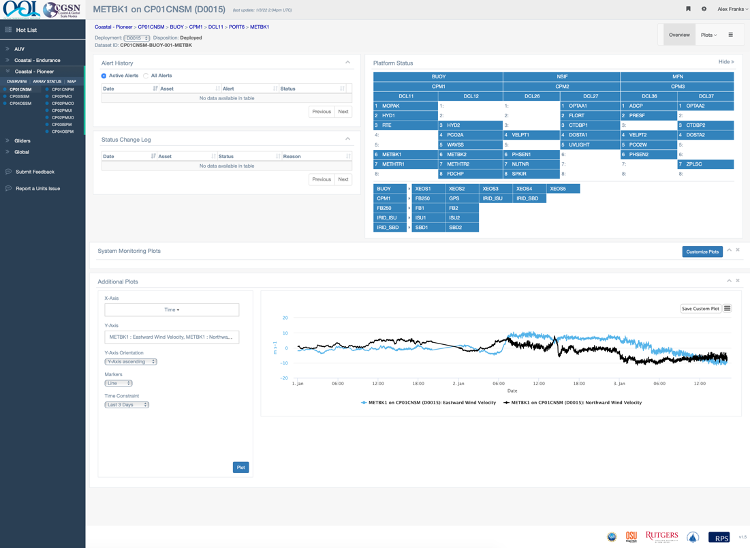

[caption id="attachment_22946" align="alignleft" width="650"] Onshore engineers are able to keep track of Irminger Sea buoys and instrumentation on this new new dashboard.[/caption]

Onshore engineers are able to keep track of Irminger Sea buoys and instrumentation on this new new dashboard.[/caption]

With a largely independent system, operators also needed a way to easily monitor status of the buoys and instrumentation. The software team created a new shoreside dashboard that allows operators to set up custom alerts and alarms based on variables being collected and telemetered by the buoy. While the buoy systems can now operate autonomously, alerts and alarms maintain a human-in-the-loop component to ensure quality control.

As operations and management of the moorings have progressed, the operations team has found opportunities to fine tune how operators and the system handle edge cases of how the system responds to hardware failures and extreme weather. In the past, sometimes conditions changed faster than the data being transmitted back to shore. This new sophisticated software automates some of the buoy’s responses to changing conditions in real time, which helps to ensure their continued operation even under challenging conditions. The decreased response time to environmental and system events using an automated system, coupled with the ability to monitor and interact remotely, has increased the reliability and survivability of OOI moorings.

Read More