Posts Tagged ‘Hilary Palevsky’

New View of Biological Carbon Pump

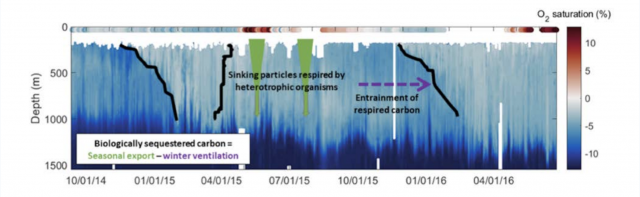

The ocean’s biological carbon pump plays an important role in the global carbon cycle. Using OOI data from the Global Irminger Sea Array, researchers discovered that much of the organic carbon exported from the surface is ventilated back to the atmosphere, rather than being sequestered long-term as had been previously thought.

Read MoreBGC Workshop Cooks Up a Recipe for Collaborative Research

Thirty-six researchers from 19 institutions from five countries converged on the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution for three days (June 16-18) to participate in a workshop designed to enhance the use of data from biogeochemical (BGC) sensors on Ocean Observatories Initiative arrays. A product of the workshop will be the “OOI Biogeochemical Sensor Best Practices and User Guide” designed to standardize the use of BGC sensor measurements and promote best practices in their research application.

In summer 2021 the NSF-funded OOI Biogeochemical Sensor Data Working Group was established to develop guidelines and best practices for using OOI biogeochemical sensor data to broaden users and applications of these data, and build community capacity to produce analysis-ready data products. The Working Group convened regular virtual meetings beginning with a three-day virtual workshop in July 2021. Members developed a draft best practices guide with explicit recommendations for end users working with data from four sensor sub-groups: dissolved oxygen, inorganic carbon parameters, bio-optics, and nitrate. The five chapters of the best practices guide cover background on the OOI arrays and the biogeochemical sensors deployed on them, data QA/QC and data access, and each of the four sensor sub-groups listed above.

Current and prospective OOI biogeochemical sensor data users gathered together with the Working Group members at the June workshop to review and discuss the best practices guide and to explore scientific questions that can be explored with these data. The discussions were lively and productive. Small breakout groups discussed scientific research ideas using OOI biogeochemical sensor data, with the hope that these discussions would kickstart research collaborations, and help inform a planned follow-on peer-reviewed publication (e.g. a Frontiers in Ocean Observing article) to present the exciting science that OOI biogeochemical data and the best practices guide will enable. The second goal of the workshop was to solicit the revisions and edits needed to finalize the best practices guide in advance of dissemination to the wider community through Ocean Best Practices.

The workshop was a huge success. Said participant Michael Vardaro from the University of Washington and a member of the OOI Regional Cabled Array Data Team, “It was a great workshop. I hope we and NSF can inspire other interested early career scientists to organize more workshops like this. They ask hard questions, which ultimately will make the program better!”

Over the past year Sophie Clayton, Old Dominion University, Hilary Palevsky, Boston College, and Heather Benway, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution have facilitated the Biogeochemical Working Sensor Data Group meetings and preparation of the best practices guide.

“We’ve spent the past year working with a great group of early career and experienced researchers on developing best practices for maximizing the use of biogeochemical data from OOI sensors, “ said Sophie Clayton.

“The workshop gave us all a great opportunity to meet in person and discuss a wide range of exciting research ideas that the OOI BGC data will enable. We were also so pleased to connect and see how much new progress we made in just three days thanks to being all in the same place together,” added Hilary Palevsky.

[media-caption path="/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/BGC-Workhshop.jpeg" link="#"]Participants at the end of a three-day Biogeochemical Sensor Workshop held at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution June 17-19, 2022. Photo: Mai Maheigan ©WHOI.[/media-caption]The working group members are: Annie Bourbonnais, (University of South Carolina), Susan Hartman (National Oceanography Centre), Hilde Oliver (WHOI), Kristen Fogaren (Boston College), Merrie Beth Neely, (Global Science and Technology – embedded contractor at NOAA), Filipa Carvalho (National Oceanography Centre), Andrew Reed (OOI – CGSN), Isabela Le Bras (WHOI), Alison Chase (University of Washington – Applied Physics Laboratory), Cara Manning (University of Connecticut), Rob Fatland (University of Washington), Ellen Briggs (University of Hawaii at Manoa), Christina Schallenberg (University of Tasmania), Ian Walsh (Freelance Researcher), Jennifer Batryn (WHOI), Christopher Wingard (Ocean Observatories Initiative Endurance Array), Jonathan Fram (Oregon State University (OOI)), Roman Battisti (University of Washington/NOAA PMEL), Dariia Aamanchuk (Dalhousie University), Jennie Rheuban (WHOI), Rachel Eveleth (Oberlin College) and Joseph Needoba (Oregon Health & Science University).

The additional participants who reviewed the draft Best Practices and User Guide and attended the workshop are: Kohen Bauer (Ocean Networks Canada – University of Victoria), Baoshan Chen (Stony Brook University), Jose Cuevas (Boston College), Susana Flecha (Spanish National Research Council), Micah Horwith (Washington State Department of Ecology), Melissa Melendez (University of Hawaii at Manoa), Tyler Menz (Stony Brook University), Al Plueddemann (WHOI/OOI), Sara Rivero-Calle (University of Georgia), Nick Roden (Norwegian Institute for Water Research), Pablo Nicolás Trucco-Pignata (University of Southampton – National Oceanography Centre), Michael Vardaro (University of Washington, OOI), and Meg Yoder Boston College.

Read MoreHilary Palevsky: From landlocked to ocean expert, teacher, mentor

Hilary Palevsky, Assistant Professor, Boston College[/caption]

Hilary Palevsky, Assistant Professor, Boston College[/caption]

Having grown up landlocked in Western Pennsylvania, Hilary Palevsky had never thought much about the ocean nor ever imagined studying oceanography. That all changed in her junior year of college when she participated in the Williams-Mystic Maritime Study Program. At the very beginning of the semester, she went to sea for 10 days aboard the Sea Education Association’s SSV Corwith Cramer. This experience turned out to be the perfect confluence of events for her future career path.

“I just fell in love with everything about the ocean – not only the science of it, but sea shanties, and maritime history and literature, “ explains Hilary. “I really wanted to do something about climate change. Realizing that the ocean plays this totally dominant role in the Earth’s climate system on human-relevant time scales, I knew that’s what I wanted to do.”

After graduating from Amherst College, she wasn’t sure what direction she would pursue but whatever it was, it would be ocean-related. Hilary took on a fellowship to study interactions between policy, science, and stakeholders through the lens of North Atlantic cod fisheries. She traveled all over the north Atlantic coast talking her way on to fisheries research vessels and small fishing boats. (As a 20-year-old woman, the former was easier than the latter). She also gave K-12 marine science education on traditionally-rigged schooners a try before she stepped on the path to getting a PhD in oceanography and a graduate certificate in climate science at the University of Washington.

Hilary is now an assistant professor at Boston College. Her research focuses on how the ocean takes up carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and the chemical, physical, and biological processes involved. A through line for her research are places that have strong seasonal cycles, which is how she came to work with OOI data. She was interested in getting measurements of how much carbon the ocean was taking up throughout the seasonal cycle in the subpolar North Atlantic. “There is a really interesting and exciting interplay between biological processes – a huge spring bloom in the North Atlantic—and physical processes, where there’s really deep winter mixing.” To understand how these two interact requires having measurements throughout the year. OOI makes this possible by continuously collecting this data, including times when it’s too cold and stormy to be out there on a boat.

Mentoring makes a difference

A major part of Hilary’s professional life now revolves around teaching. She is one of those exceptional teachers who makes science accessible and interesting. Hilary is also one heck of a mentor.

“My understanding of mentorship and role modeling have changed over time. I didn’t feel like the gender identity of my mentors mattered to me [as an undergraduate] because I had awesome women mentors. I had a great undergraduate senior research advisor, for example, who modeled other things [than just research] for me. She was married to another woman, I met and got to know her wife. From her, I learned how to figure out how to be a person doing science rather than a scientist trying to be a person.” Hilary actually met her spouse for the first time in her advisor’s office!

Having such mentoring and role model representation early on in her career were particularly important to Hilary as a woman and a queer person. She didn’t experience the barriers that often exist because she had role models who demonstrated how she could survive and thrive in the scientific academic community.

“It was only later on in my career, when all of my advisors were straight men, that I recognized that there was really something important about my early mentors. But today I also recognize that all of my mentors have provided important things along the way. I have had male mentors who have been great role models for me as a woman. I’ve had straight mentors who have supported me as a queer woman with a spouse who is transgender.”

Hilary’s experiences have made her adamant about the importance of being a good mentor, particularly for people who don’t share the same identities. “I think about myself as a white woman who now mentors undergraduate and graduate students in a field that is overwhelmingly white. I constantly ask myself what do I have to do to be an effective mentor to students of color and coming from backgrounds and identities that are different from mine?”

Until a truly inclusive and diverse science community exists, Hilary believes it is imperative that leaders in academia find ways to be effective mentors for people who don’t either look like them or share some or all of their identities. “While the Geosciences has made some progress in gender parity, the representation of people of color has not made the same gains. The fact that I as a white woman have a faculty position shows there’s been progress, but we have to start making this happen for Black women, Indigenous women, trans women, all of whom haven’t been making these same gains as white women.”

Profiles of Other Exceptional OOI Women

[caption id="attachment_20422" align="alignnone" width="300"] Sophie Clayton, Assistant Professor, Old Dominion University[/caption]

[caption id="attachment_20424" align="alignleft" width="300"]

Sophie Clayton, Assistant Professor, Old Dominion University[/caption]

[caption id="attachment_20424" align="alignleft" width="300"] Hilde Oliver, Postdoctoral Scholar, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution[/caption]

Hilde Oliver, Postdoctoral Scholar, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution[/caption]

Read More