Posts Tagged ‘Technology’

New Controller Latest in OOI Innovations

Having equipment in the water around the clock for six months at a time provides many challenges for the land-based OOI engineering team charged with keeping the equipment operational so there is a continual flow of data to shore. Maintaining consistent, reliable power for the ocean observing equipment is at the top of this list of challenges.

OOI’s data-collecting instruments attached to the moorings run on batteries charged by renewable wind and solar energy. OOI is in the process of replacing the current solar panels with new panels that are more efficient at generating energy, even when shaded. To supplement this upgrade, the OOI arrays are also being outfitted with a brand-new solar controller to manage the energy going into the batteries. Like with the new solar panels, OOI engineers looked for a controller that was available commercially for easier repair and replacement.

“What was important to us was finding a way to use these new solar panels in the best, most optimal way,” said Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI) engineer Marshall Swartz. “We looked for a company that would help us specify and build a customized algorithm for a controller that would optimize the functionality of the panels by taking into account battery temperatures.”

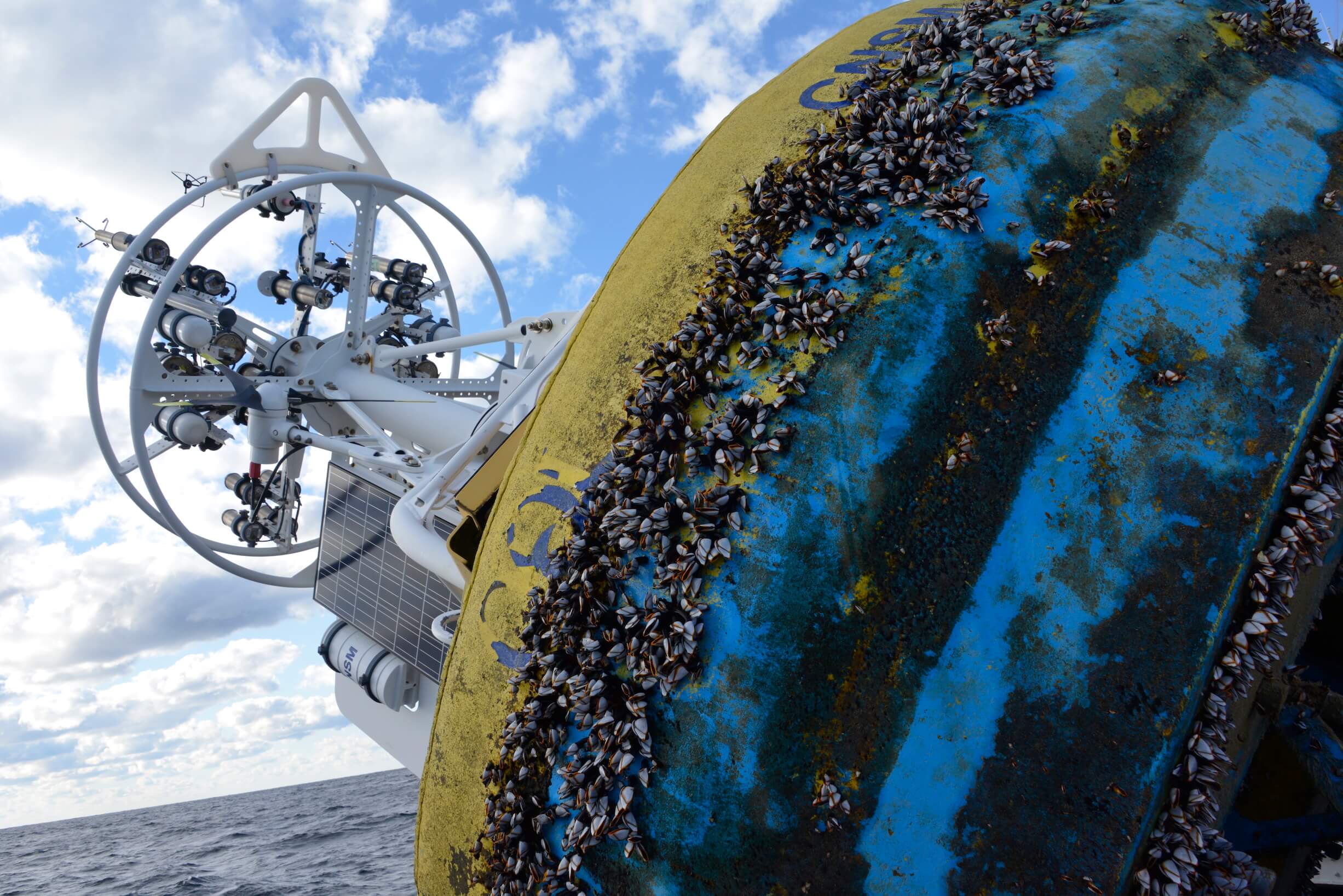

[media-caption path="/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/DSC0486-2.jpeg" link="#"]Buoys get quite the workout when they are in the water for six months and more. Powered by wind, solar, and batteries, OOI has recently improved the way energy from the solar panels is managed with new controllers. Credit: ©WHOI, Darlene Trew Crist. [/media-caption]

Some larger, older controllers can consume up to 3-5% of the energy coming into the device, but the new controller is smaller and more efficient, helping to optimize the amount of energy harvested.

Temperature conditions play a big role in how effectively the energy is managed. Changing battery temperatures require the controller to adjust its charge settings to maintain battery life and capacity. The controllers used on OOI moorings sense battery temperature and automatically adjust to assure best conditions to assure reliable operation.

“It’s really essential for us to maintain the proper charge levels for existing temperature conditions,” said Swartz. The OOI buoys encounter a wide range of temperatures: from subfreezing temperatures up to 40°C (over 100°F) when a buoy is sitting in the parking lot before it is deployed. When the buoys are deployed, water temperatures can vary widely from -1 to 33°C (~30 to 91°F), depending on seasonal conditions.

The new controller automatically regulates the amount of electricity going into the battery under such varying temperature conditions. If the wind turbines are generating more energy than the battery needs, for example, the controllers direct excess power into an external load that dissipates heat and adds resistance to the spinning of the wind turbines, preventing the turbines from spinning too fast, possibly damaging their bearings.

“As parts of the OOI infrastructure need replacing or to be upgraded, this offers us the opportunity to find more efficient, and often times, off-the-shelf, less-expensive replacements that will help us keep the arrays functioning and data flowing,” Swartz said. “It’s a winning combination for all parts of the operation.”

Read More

Shedding Light on Wave Energy Harvesting

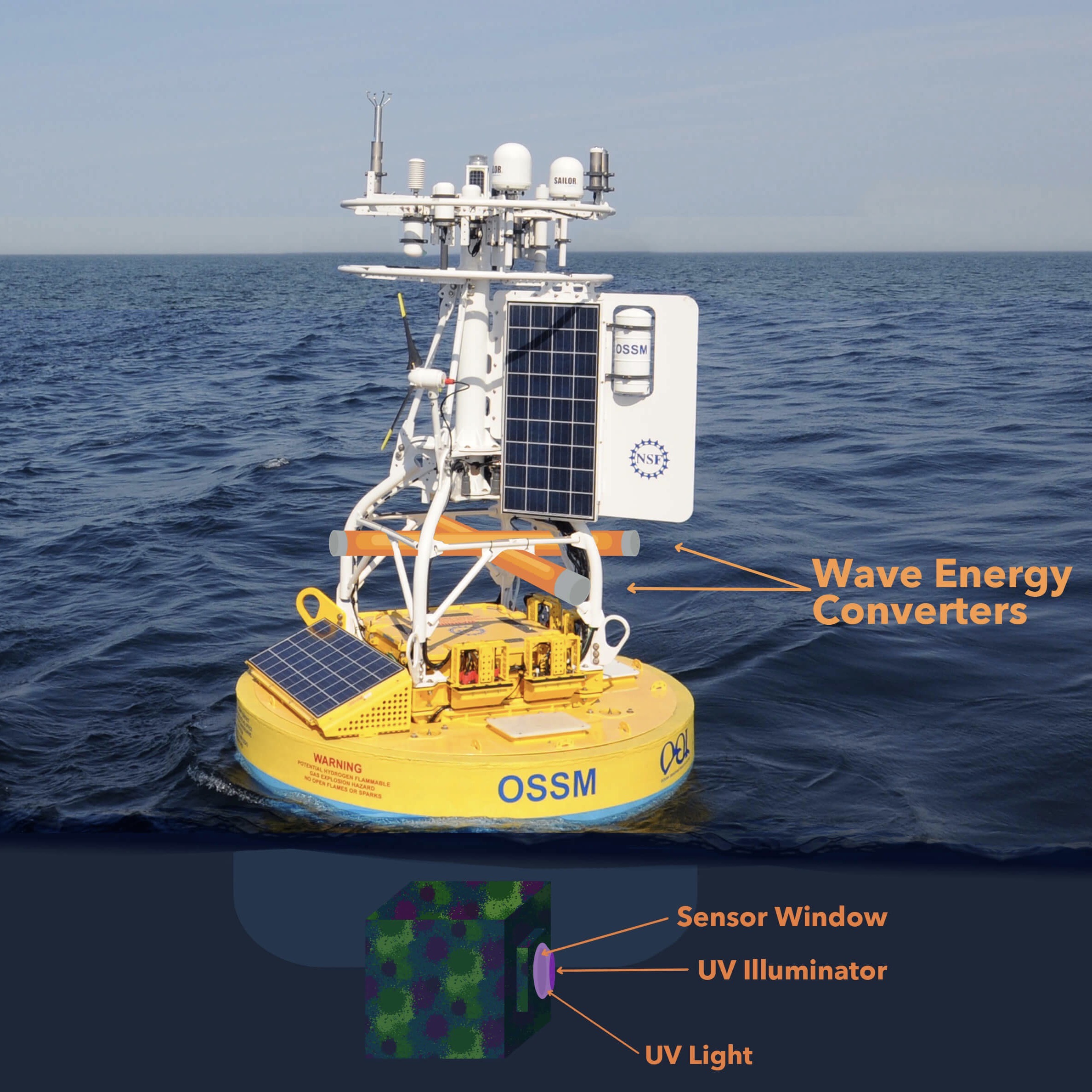

Two entrepreneurs and two engineers recently teamed up to develop a wave-based energy generator with the potential of powering the Pioneer Array, while also providing energy to a new, longer lasting, and potentially more effective way to keep the array’s sensors free and clear.

The Department of Energy thought the idea had such potential that it awarded the team a Small Business Technology Transfer (STTR) grant that will allow them to develop a proof of concept of this system by late March 2021.

The development team consists of grant Co-Investigator Matt Palanza, program engineer for the Ocean Observatories Initiative (OOI) at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI), Megan Carroll, a research engineer at WHOI and expert in the dynamics of moored systems, and Principle Investigator Julie Fouquet and Co-Investigator Milan Minsky, principals of 3newable, LLC, a firm dedicated to the development of small-scale wave energy converters. Fouquet started by developing and testing wave energy converter concepts on land, to choose an efficient, low-cost and flexible approach. Minsky brings to the team extensive experience in developing first-generation ultraviolet LEDs for medical and industrial applications that she will put to good use in designing a system to tackle serious biofouling conditions that plague all equipment put into the ocean for extended periods.

“The concept of harnessing wave energy at the Pioneer Array, then powering an ultraviolet LED anti-fouling light, which could possibly keep the array functioning much longer, would be a win-win. If this combination is proven here, it could have widespread application in oceanographic research and aquaculture applications, with tremendous potential for cost savings,” said Palanza.

Striving for Good Environmental Outcomes

Striving for Good Environmental Outcomes

Julie Fouquet founded 3newable LLC in 2015 with the goal of capturing electrical power from water waves as a source of renewable power. Previously, companies wanting to commercialize wave energy generation had failed while attempting to build utility scale systems, which were extremely costly. Years of experience in the semiconductor industry taught Fouquet that product development requires multiple design-build-test-redesign cycles. Companies developing utility-scale systems ran out of money before reaching a viable product. She chose to focus her efforts on developing an efficient and cost-effective small-scale wave energy converter that could fit into the back of an SUV and on a runabout boat.

Having worked together for decades, she and Minsky – now vice president of product at 3newable – teamed up to find out what sort of applications in the oceanographic community could use a small-scale wave energy converter.

After many meetings, they concluded that the Pioneer Array buoys would be a good testing ground. Palanza agreed and the team set out to write a proposal that would capitalize on their collective talents to provide a potential real-world application of wave energy and anti-biofouling technology.

The Pioneer Array buoys are already powered by wind and solar, but the wave energy converter offers a way to keep the sensors clear and recording for longer time periods using UV LED lights, possibly extending trip intervals needed to service the arrays.

Like most things in spring 2020, COVID caused delays in the launch of this project. DOE announced the award in May, but the actual award was delayed until early August, which potentially squeezes the March deadline for producing the feasibility study. From there, the team hopes to move forward to Phase 2, which would involve construction of both the wave energy conversion and UV anti-fouling prototypes and testing in the field.

“We are already working in a distributed way with processes in place so COVID hasn’t impacted our progress in analyzing data and developing lab tests,“ said Minsky. “But the interesting thing about the pandemic is that it has really propelled the UV LED field along as people explore its potential medical uses. Prices are dropping and quality is going up so we will be able to take advantage of these advances as we go about commercializing this module.”

During Phase 1, the team will be striving to answer the following questions:

· How much power is needed to run UV anti-biofouling equipment at the array?

· Can enough power be generated to meet the demand?

· How big of a wave energy converter unit will be needed?

· What are the unit size limitations if attached to the array?

“We all are excited to get this project launched. There’s a real need for improved anti-biofouling technology, and with the emergence of UV LEDs powered by waves onsite, it’s a sound solution with a potentially positive environmental impact, “added Palanza.

Read More