Posts Tagged ‘Coastal Surface Piercing Profiler’

Exploring the Coastal Surface Piercing Profiler (CSPP): Capabilities, Challenges & Impact

The Coastal Surface Piercing Profiler (CSPP) is an important component of the Ocean Observatories Initiative (OOI), uniquely designed to collect high-resolution data from the ocean’s surface to the seafloor over the Oregon Shelf. Importantly, as the name implies, the CSPP does not stop at the ocean surface but some of its sensors actually pierces the interface into the near surface atmosphere. Operating in a highly dynamic environment, the CSPP provides valuable datasets that enhance our understanding of ocean-atmosphere interactions, nearshore processes, and biological activity in the upper water column.

In this interview, Jon Fram, co-PI and Program Manager for the Endurance Array (EA), explores the technical capabilities of the CSPP, the difficulties of operating in dynamic coastal conditions, and the significance of its unique datasets. With its ability to profile up through the air-sea interface and its collection of advanced sensors, the CSPP bridges critical gaps in ocean observation. Jon discusses the practical realities of deploying and maintaining the profiler, including a notable recovery effort that illustrates the complexity of coastal oceanographic work.

How does the CSPP operate in such a dynamic environment, and what are some of the challenges associated with deploying and maintaining it?

In between profiles, CSPPs park near the seafloor where currents from waves and tides are relatively calm. As CSPPs winch themselves up to the air-sea interface, they measure winchline tension and they alter their profiling speed to keep the tension constant. This behavior enables CSPPs to surface when waves are up to 3 meters high without the winchline over-wrapping or experiencing snap loads. We monitor conditions so CSPPs don’t profile when seas are too rough. Most of a CSPP’s battery energy goes to operating its winch, so CSPPs need to be recovered/redeployed every 2-3 months and they are limited to 2-4 profiler per day during each deployment (when conditions are sufficiently calm).

What types of sensors and instruments are on the profiler, and what specific data do they collect?

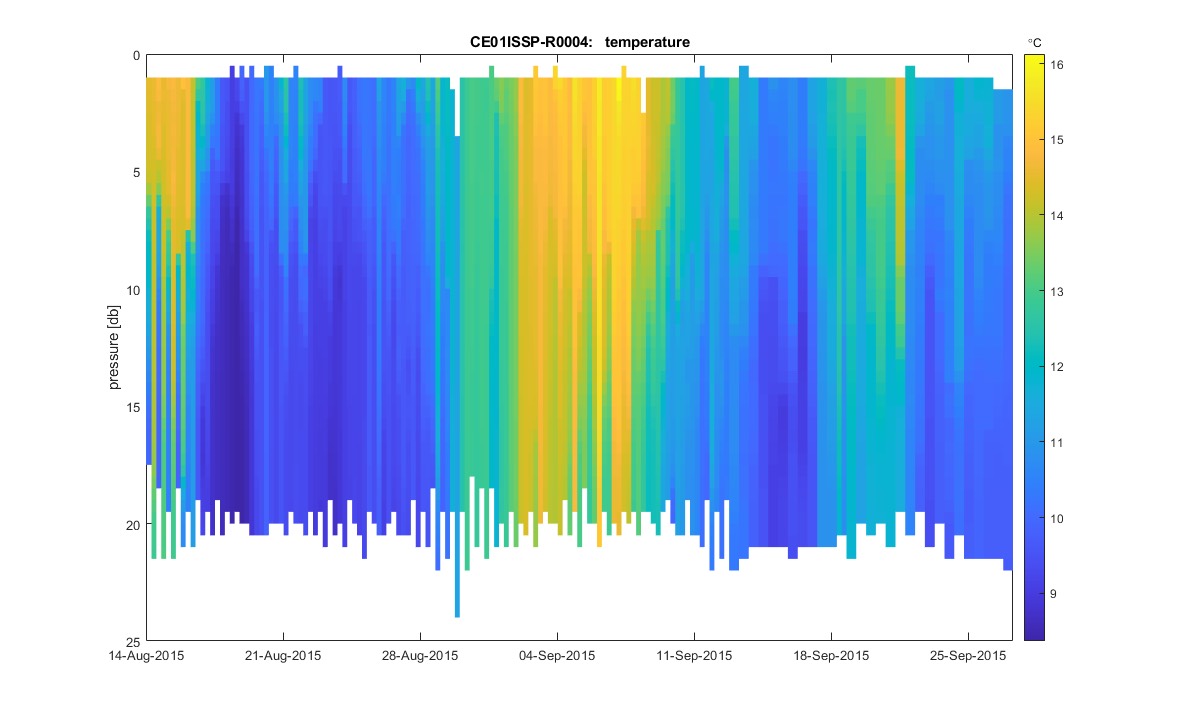

CSPPs average 25 cm/s as they profile upwards. Their CTDs sample at 16 Hz, which corresponds to a measurement every 1.5 cm. Their ~1 Hz instruments include dissolved oxygen (DOSTA), point velocity (VELPT), nitrate (NUTNR), spectral irradiance (SPKIR), photosynthetically active radiation (PARAD), and chlorophyll-a—optical backscatter—CDOM (FLORT). The CSPP is a particularly useful platform for the optical attenuation and absorption instrument (OPTAA), which can be used to characterize phytoplankton communities at the top of the water column.

What are the unique capabilities of the CSPP, and how do its datasets differ from those collected by other platforms within the OOI?

The CSPP is OOI’s only profiler that samples up to the air-sea interface.

How has the profiler contributed to understanding the relationship between atmospheric and oceanic processes in the area?

So far, OOI’s CSPPs have been used to fill in time gaps in mooring data and to fill in spatial gaps between mooring near-surface (NSIF) and benthic (MFN) data. Inshore and shelf CSPP data have been used together to calculate cross-shore exchange of nitrate, which is increased each spring due to coastal upwelling. CSPPs measure at the air-sea surface, so their measurements could be used to validate satellite data.

How could the near-time data transmission from the profiler benefit research efforts or inform stakeholders such as fisheries, conservation groups, or local communities?

Datasets are available within a week after each deployment. They can telemeter all data when they are on the surface at the top of each profile, however, we transfer only data needed for operational decisions to reduce the chance of winchline fouling.

Can you share an anecdote about a particularly challenging or rewarding moment during the deployment, maintenance, or operation of the profiler?

One challenging moment occurred 06 April 2019. During a storm, rough seas (~7m significant wave height, >1 m/s currents) dislodged our 25m depth Oregon Inshore CSPP and deposited it 75 nm north on a pocket beach in Ecola State Park. We climbed down to it, pulled it above the high tide line, disassembled it, and packed it out piece-by-piece up a steep trail in pouring rain. The Endurance Array inshore CSPP and adjacent surface mooring measure the northward fresh/turbid surface current that hugs the Pacific Northwest coast during winter, and which strengthens during storms. This is one example of how the CSPP data can be used to improve our wind, wave and current forecast models.

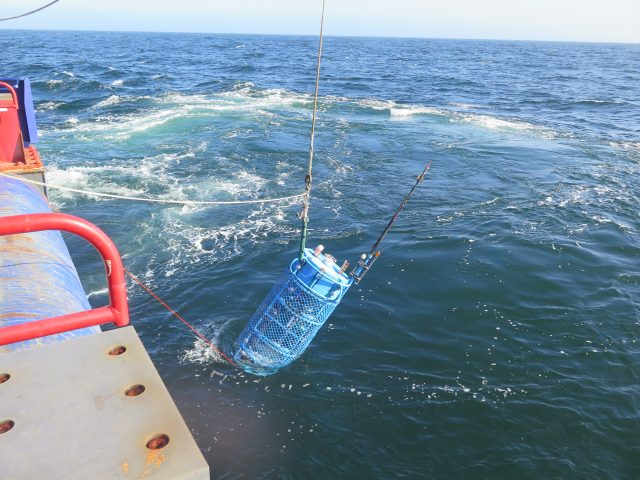

[caption id="attachment_35671" align="alignnone" width="640"] Deployment of CSPP. (c) Jon Fram[/caption]

[caption id="attachment_35670" align="alignnone" width="640"]

Deployment of CSPP. (c) Jon Fram[/caption]

[caption id="attachment_35670" align="alignnone" width="640"] Beach recovery effort. Pictured: Ian Black, OSU. (c): Jon Fram[/caption]

Read More

Beach recovery effort. Pictured: Ian Black, OSU. (c): Jon Fram[/caption]

Read More Tackling Sea Surface Sampling Issues

The sea surface is the hardest place to work, according to Jonathan Fram, Project Manager of the Coastal Endurance Array. That’s because at the surface, waves are constantly sloshing around. At any time, a large wave can tug on mooring winch lines, creating sudden tension, which can wear down cables and even cause them to break.

Scuba divers know that surface waters are rough, but below a certain depth—about one wave orbital below the surface—the waters calm significantly. Unfortunately, a lot of great science takes place at the surface, so it’s important for sampling instruments like the Coastal Surface Piercing Profiler (CSPP) to be able to withstand the waves at and near the surface. Fortunately, OOI engineers have found ways to meet the many challenges of working in this rough environment.

“The Coastal Endurance Array Team has made changes to the CSPP to make it more robust, so that we can get the kind of continuous time series that are so valuable to scientists,” said Fram.

A CSPP spends most of its time near the sea floor, but either two or four times a day, the profiler winches itself up to the surface, taking samples as it ascends. Once it reaches the surface, the profiler sends its data back to shore and then quickly returns to the safety of the seafloor. Profilers are important ocean observatory tools because they can help capture what is happening at certain depths where stationary instruments aren’t present. “We’ve had times where you get a persistent chlorophyll bloom at a certain depth where there is zero mooring data,” explained Fram. “So the CSPP sampling is needed to make sense of what’s happening. It’s impossible to have all the instruments at all depths. The CSPP fills in this gap.”

Last year, the Coastal Endurance Array team reviewed their activities looking for ways to reduce lost time at sea. One thing they discovered was that the anchor systems of the CSPPs were unreliable. To deal with this problem, the team created a new kind of anchor. The old profiler anchors had a chain between the profiler and anchor that helped dampen the waves so that the device was not tugged on when resting in between profiles. The chain, however, made it difficult to deploy the anchor in an upright position. Anchors need to be deployed upright so their recovery floats can be acoustically released. The team redesigned the anchors so they now behave like a weeble wobble toy that is weighted so it always rights itself. This new design makes it hard to deploy an anchor upside down, making the anchors more reliable.

The team also made updates to the modems that send data to shore. When the CSPP is at the surface, the winch must stay on because it keeps the antenna vertical. This time-on takes up about a quarter of the battery power. To reduce the power demand, the team switched out some of the iridium modems for cellular modems, which has allowed the CSPPs to send data more quickly. A faster modem means that the profiler spends less time at the surface, not only saving power, but reducing the risk of being damaged by a large wave. The team is currently working on upgrading to faster cellular modems that can connect further from shore.

“At the same time we are making these updates on the Oregon Shelf Mooring, we’re also implementing them on the Washington Shelf Mooring,” said Fram. “So an improvement on one platform is also leading to an improvement on another platform.”

A third innovation involves improvements to the batteries.

“When waves tug on the winch, it goes from being a power sink to a power source. That sometimes creates power spikes that can fry the connectors. So we’ve rewired the batteries to make them more robust,” explained Fram. The rewiring is expected to reduce the number of power failures and keep the CSPPs running continuously. “Since April when we first started using the rewiring scheme, we’ve had four profilers in the water with no problems for six weeks,” said Fram.

The team also is in the process of replacing batteries that power the profiler with their own design of rechargeable batteries. While OOI engineers prefer to use commercially available parts for easier repair and replacement, when parts on the market don’t fit their needs, they design their own. The new batteries will be more reliable than those they are replacing. The newly designed batteries will also be deployed on the wire-following profilers on the Coastal Pioneer Array.

“My focus is on making all of the Coastal Endurance instrumentation work,” said Fram. “When we’re able to get a full three months’ deployment through the winter, through super rough seas, that makes my day. Making improvements is what I look forward to the most.”

Read More