Posts Tagged ‘Katie Bigham’

A Post Doc Project with Ten Years of Ready-made Data

Katie Bigham has been around OOI for nearly a decade. Her involvement began in 2014 when she was an undergraduate at the University of Washington (UW) and took part in the marathon 83-day OOI Regional Cabled Array’s (RCA) final construction cruise that installed over 100 instruments, 9 moorings, 18 junction boxes and thousands of meters of extension cables. At the time, she was onboard as part of UW’s VISIONS program, an at-sea education program designed for students to experience all aspects of seagoing research and life aboard a global class oceanographic research vessel hosting a remotely operated vehicle (ROV). With a taste of Axial Seamount and hydrothermal vents on the ocean floor provided by her first sea-going experience, Katie landed on a direct career path to where she is today — a benthic ecologist post-doc at UW, using OOI data. It’s a repeat pattern for Katie. She first used RCA OOI data to write her senior thesis focused on life thriving at Southern Hydrate Ridge methane seeps before graduating with a degree in Oceanography from UW in 2017.

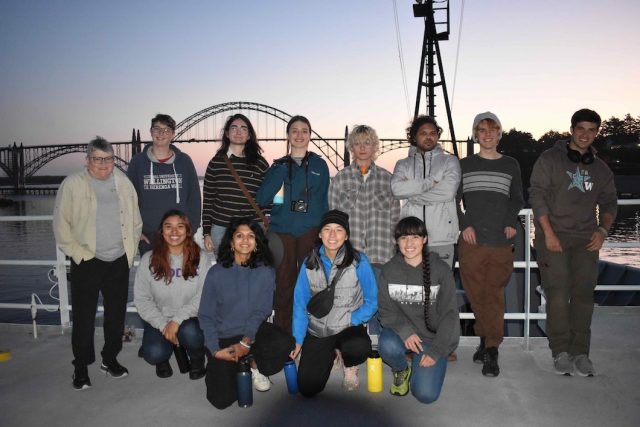

[media-caption path="https://oceanobservatories.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/2Katie_Studenst_sm-20230908_200403_startL4_ME-copy-scaled-1.jpg" link="#"]Chief Scientist Katie Bigham (back row, second from left) and VISIONS’23 students on the R/V Thompson during Leg 4 of the OOI-RCA operations and maintenance cruise. Credit: M.Elend, University of Washington. [/media-caption]After graduation, Katie took a couple of gap years, where she worked as a research associate for the OOI RCA and continued to go out on RCA’s annual recovery and deployment expeditions. She then decided to go for a PhD, relocating to Victoria University of Wellington in New Zealand during the height of COVID. While other colleagues’ research was stymied by the effects of the worldwide lockdown, Katie, luckily, had access to years of data on benthic communities in Kaikōura Canyon, a highly productive submarine canyon. As a benthic ecologist, she is interested in how and why biological communities change over time. Her dissertation focused on the impact of the magnitude 7.8 Kaikōura Earthquake in 2016 on the benthic community and it’s recovery. To assess this, she used co-registered detailed bathymetric and multicore data, as well as repeat photographic surveys from both before and after the disturbance.

“For a lot of these deep communities, we don’t really know what the baseline is for them. We don’t know what normal is,” Katie said. “I’m really interested in how to get the most out of multiscale, complex data sets to answer these important questions. Ship time is expensive. It’s hard to work in the deep sea and conditions there are really tough on instruments and equipment. That’s why projects like OOI are a great way to provide critical data over the long haul.”

During her PhD, Katie applied for and was awarded a National Science Foundation Postdoctoral Research Fellowship within the Ocean Sciences Division. “Funny, but my original thought was to try to Pandemic-proof my post-doc. I wanted to formulate a project that would advance our knowledge of benthic communities thriving in dynamic environments and be achievable in a 2-year time period. I was looking for something that would be cohesive and with readily available data that wouldn’t be at risk from COVID impacts, such as requiring laboratory studies. After considering available datasets, from my senior thesis work, I remembered the tens of thousands of images and terabytes of video collected at Southern Hydrate Ridge (SHR) since 2008 during the early days of the RCA and follow-on annual cruises, as well as the now nearly decade of data provided by the cabled instrumentation. Using these data, I was able to immediately start asking questions about long term temporal changes in biological communities associated with methane seeps. The wealth of high quality imagery collected at SHR, is nearly unparalleled for these environments.”

Katie is using imagery from the SHR digital still camera and ROV imagery for her research project. The cabled camera located at the Einsteins’ Grotto methane seep turns on its lights every half hour, takes three pictures, and then turns off. “It’s a highly dynamic environment where we’ve seen significant changes since the camera and the other equipment was first put in place there. This site hosts ‘vagrants’ or non-endemic megafauna, along with chemosynthetic bacteria that form extensive mats and clams with symbiotic bacteria. But, we also see rockfish, flounders, hagfish, eelpouts, and other visitors that come into the area, as well as soft corals and Neptunea nurseries because we think the seep is acting as a kind of an oasis for these organisms.”

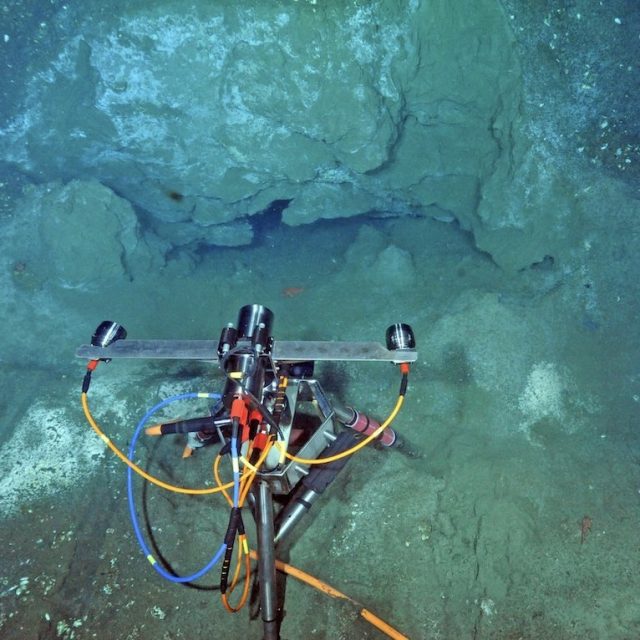

[media-caption path="https://oceanobservatories.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/For-Katies-piece-good.camdsr1767_02826.sm_-scaled-2.jpg" link="#"]The SHR digital camera located at the Einsteins Grotto methane seep provides Katies with imagery for her research. Credit: OOI/UW/CSSF; Dive R1767; V14. [/media-caption]The visual imagery available is helping Katie better understand cold seeps and how and why they are attracting other species. “Better understanding of methane seeps is important because of the potential interest in mining them, and because places like SHR are deemed “essential fish habitats.” Hence, we need to understand their relevance to fish stocks, including that perhaps they may be serving as nursery areas. Over 1,000 sites along the Cascade Margin are known to venting methane, but less than ~five have been studied in any detail.”

The imagery allows researchers like Katie to begin to look at the temporal dynamics of these communities and determine whether they respond to particular cycles, such as tides, changes in the chemosynthetic concentrations, or pulses of macroalgae from the surface, as well as the long term impacts of ocean warming. “The images are helping us understand the colonization of specific organism types and how benthic communities are using these sites over time. Because the datasets are so high-resolution with data every half hour, we can look at larger annual cycles and changes from season to season and year to year,” Katie added. Other SHR co-located cabled instrumentation also allows for investigation of changing conditions due to seismic events, for example.

The Challenges of Big Data

Katie’s task over the next two years is not an easy one. The digital still camera alone produces over 50,000 images a year. These data, coupled with terabytes of 4K and HD imagery, as well as thousands of images taken during ROV dives in the area, creates a huge amount of imagery to process. She’s tackling this effort in two stages: The first is to bring in machine learning and computer vision techniques to aggregate the datasets. Once that is accomplished, there’s the bigger task of looking at the imagery and classification output to determine what can be learned about the inhabitants of the seep area.

The first task to incorporate AI into helping sort the imagery is to label various features. “Obviously, the holy grail would be, the computer just does it for you. But because this still camera is looking at generally the same scene all the time, it’s ripe for putting an event detector or machine assisted annotation, where the computer can help differentiate today’s picture from yesterday’s picture,” she added. With such computerized assistance, researchers like Katie can then spend their time looking at the animals and observing their behavior rather than having to annotate each image. She gave an example: sometimes a crab will find a home on the camera and hang out there, blocking images of the area. A computer “trained to identify when this happens,” could allow researchers to avoid this occurrence when they can’t see behind the crab.

“I’m super stoked about this project. It’s been an exciting thing to be working on and it’s been really cool to bring together my scientific background and access to RCA-OOI data,” Katie said. “I’m developing automated digital analyses techniques that when I worked on my undergraduate thesis thought it’d be so cool to do and I’m doing it now.”

With a powerful computer and multiple monitors in hand, in two years when her post doc ends (December 2025), Katie will have moved the world of AI forward to analyze an unprecedented amount of data within this marine ecosystem, resulting in one or more scientific papers about the temporal dynamics of benthic communities and how and why they change over time–in her words “a nice, cohesive, achievable effort!”

Read More

RCA’s Ninth Expedition: Best Laid Plans

Written by Deborah Kelley, PI of the Regional Cabled Array, September 17, 2023

The Regional Cabled Array, spanning the Cascadia Margin and Juan de Fuca tectonic plate and water depths of ~260 ft to 9500 ft, is an engineering marvel. It is the most advanced underwater observatory in the oceans comprised of >900 km of high power- and -bandwidth submarine fiber optic cables, a highly diverse suite of >150 instruments, and state-of-the-art moorings with instrumented profilers, which since 2014 have traversed >50 million meters of ocean water! The underwater substations and instruments are installed in some of the most extreme environments on Earth, including the most active submarine volcano off the Oregon-Washington coast ‘Axial Seamount’. Here, extension cables traverse glass covered lava flows and instruments are inserted into underwater, acidic hot springs, hot enough to rapidly dissolve aluminum and melt lead. Profiling science pods on moorings that traverse ocean depths from ~650 ft to 16 ft nine times a day, must be ‘smart’ enough to keep “their heads down” when storms, common in the waters of the NE Pacific Ocean, create waves reaching 30 feet in height or more. Yet, it is within these environments that the cabled observatory has thrived, largely due to its design, rigorous testing, and the hard work of the RCA Team, and Jason and Thompson crews during the annual operations and maintenance expeditions, such as the one nearing its end now: VISIONS’23.

[media-caption path="https://oceanobservatories.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/Katie_Studenst_sm-20230908_200403_startL4_ME-copy-scaled-1.jpg" link="#"]First time RCA Chief Scientist Katie Bigham (top row, second from left) with Co-Chief Scientist J. Nelson (far left), RCA technician Andrew Paley (top row, far right) and Leg 4 VISIONS students. Katie was a VISIONS’14 student. Credit: M. Elend, University Washington, V23.[/media-caption]Planning for the RCA 2023 cruise began over a year ago as there is a high demand for NSF’s global class ships that operate throughout the worlds’ oceans. Scheduling is a complex process with lots of moving parts involving minimization of transit lengths, awareness of optimum weather windows, and researchers’ schedules. As soon as lasts year’s cruise ended, RCA instruments recovered in the Fall of 2022, were sent back to vendors for calibration and refurbishment, parts and cables were ordered, and the RCA teams’ eyes were already looking to this year. By late Spring, most of the refurbishment and integration testing of platforms and instruments was complete, the four Legs were planned out in detail, and the nearly 144 berthing assignments were finished. The careful layout of equipment on the aft deck of the Thompson was of critical importance, with nearly 200,000 lbs of gear on the fantail and the need for deck space free of gear to allow for mooring cables to be recovered and redeployed.

So that brings us to now, nearing the end of Leg 4, which will end on September 18 when the Thompson arrives back to Newport, Oregon. Working at sea is just tough, no way around it, and best laid plans are often adjusted before even leaving port (such as happened at the start of Legs 1 and 3) as the weather gods do not care about our schedule. The prior three Legs experienced numerous perturbations due to the loss of a week of operational days when the ROV Jason could not dive due to bad weather and additional loss of time due to ROV issues. Plans were adjusted on the ‘fly’ over and over again to best accomplish all of our goals, including the recovery and re-installation of >100 instruments. Because of this, some work was pushed out into Leg 4, an already complicated Leg because it was especially dependent on having good sea state conditions due to the planned installation and recovery of two deep profiler moorings, the largest of which rises >8000 ft above the seafloor at the base of Axial Seamount.

[media-caption path="https://oceanobservatories.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/Float.jpg" link="#"]The float for the Deep Profiler mooring at the Oregon Offshore site being brought onboard the Thompson. Credit: M. Elend, University of Washington; V23.[/media-caption]Almost immediately, Leg 4 plans were adjusted following the first operation – the recovery and reinstallation of the Deep Profiler Mooring at the Oregon Offshore site. The communications and power ‘dock’ at the base of the mooring would not respond after plugging in the seafloor extension cable that connects it to a small substation (junction box) on the seafloor. While the engineers tested various aspects of the cable, and puzzled over the cause, the RCA team continued their work at the Slope Base site. There, the Deep Profiler mooring cable was cleaned, and the instrumented profiling vehicle deployed in 2022 was replaced. Following this operation, the Thompson transited ~ 18 hrs to the base of Axial Seamount, where, instead of turning the mooring, it was decided to just swap out the vehicle, similar to Slope Base.

[media-caption path="https://oceanobservatories.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/getting-ready-to-bring-in-the-cable.sm_.PD01B_20230909_132549_recovery_ME-copy-scaled-1.jpg" link="#"]RCA engineers and ship crew getting ready to spool cable onboard from the Offshore Deep Profiler Mooring. Credit: M. Elend, University of Washington, V23.[/media-caption]With this work complete, a series of dives was planned to support researchers’ projects funded by the National Science Foundation outside of the Ocean Observatories Initiative. These dives were to include sampling of hydrothermal vent fluids to investigate viruses and microbes in these extreme environments, the recovery and installation of cabled CTD instruments to test the hypothesis that highly saline fluids are flushed from beneath the seafloor shortly following an eruption, and the recovery of a cabled multibeam sonar (COVIS) focused on making unique fluid flux measurements in the ASHES hydrothermal field. Time allowing, equipment on the Thompson would be used to “talk” to an acoustic array (FETCH) installed in the volcanoes’ caldera for investigation of deformation within this highly active volcano.

There was, however, a small window to complete this work. After investigation of the Deep Profiler Mooring at the Oregon Offshore site, it was determined that the Thompson would need to transit nearly 300 miles back to this area, to install a new extension cable, and/or recover and redeploy the mooring with the one just recovered at the beginning of Leg 4 – an exercise that could take 2-3 days. Indeed, Jason had other ideas because while working at the summit of Axial, there was an issue with the specialized hydrothermal vent sampler on the vehicle, followed by a failure of the power system, preventing more dives. The Jason team worked very hard overnight to fix the power supply, but with ever decreasing time to get the Deep Profiler work done back on the margin, it was decided to abandon remaining work at Axial (a very tough decision as this would impact researchers work over the entire next year) and head to the Offshore site. This also allowed optimal use of the transit time to thoroughly test the repaired power system for Jason. It also provided time for the APL engineers to ready a new extension cable for the Deep Profiler mooring, hoping that this simple fix would solve the problem, and to catch up on much needed sleep. With huge relief, the replacement of the extension cable did the trick on the first dive at the Offshore site. The docking station powered up and the vehicle completed its test profiling run — opening up a three-day window for additional work.

[media-caption path="https://oceanobservatories.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/ratail-sulis_20230916210321_rattail_probe_closeup.jpeg" link="#"]A rattail fish came to investigate the UFO fluid sampler as it obtained fluids for Dr. Rika Anderson at Marker 113, a diffuse flow site in Axial Caldera. Credit: UW/NSF-OOI/WHOI, Dive J2-1559, V23.[/media-caption]With a sigh of relief and desperately wanting to support the external researchers work, Chief Scientist, Katie Bigham, asked Captain Eric to turn the ship around and head back out to Axial Seamount. So away they went, following the same track line they had completed less than 24 hrs before. During the next 34 hrs, Jason pounded out the dives and completed all but the FETCH work, before it was time to once again head back to Slope Base to complete two final tasks.

The above description is only part of what goes on during the various legs of these RCA expeditions. It is hard to convey what it is like to be a Chief Scientist on an RCA cruise. As with this cruise, decisions must be made rapidly, but also strategically, with an eye towards the end of a leg and cruise – “Will this decision prevent other work from happening? What is the weather going to be like in 2-3 days? What is the status of equipment? How are the students doing and how are their projects going? Do they need help? Is the team getting enough sleep? Should we transit to another site to help with this? On and on it goes…Awareness of these questions and outcomes are always in a Chief Scientists’ thoughts and are combined with the everyday tasks of writing plans for the next day and operational reports.

This was Katie’s first time being a Chief Scientist. She has done an exceptional job making adjustments to our “best laid plans” on a cruise that has been one for the books in the near decade of RCA operations and maintenance expeditions.

For more information on the RCA’s ninth operations and maintenance expedition, visit here.

Read More

Katie Bigham: From VISIONS Student to Co-Chief Scientist

Katie Bigham feels like her journey with the Ocean Observatories Initiative (OOI) has come full circle. She first visited Axial Seamount as a University of Washington (UW) School of Oceanography undergraduate participant on the Regional Cabled Array (RCA) VISIONS 2014 program when the underwater observatory was being installed. This summer, she returned to Axial Seamount on her seventh cruise, this time as a Co-Chief Scientist.

[media-caption path="https://oceanobservatories.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/Katie_V15_byLauren_DSC_0069.sm-copy-scaled.jpg" link="#"]Katie Bigham on the R/V Thomas G. Thompson. Credit: L. Kowalski, University of Washington, V15.[/media-caption]Katie was excited to step into the role of Co-Chief Scientist on the fourth leg of the annual RCA operations and maintenance cruise (VISIONS’21). She previously participated in many other roles on the ship and was looking forward to a new challenge sailing as a Chief Scientist aboard a global class research ship.

Her responsibilities as Co-Chief Scientist included much planning and communication during the round-the-clock operations and numerous remotely operated vehicle dives. “It’s really about keeping everybody who’s invested in the voyage up to date, from the RCA team itself, to the Captain and crew, to the VISIONS’21 students, to the RCA team shore-side,” she says. Katie credits the success of leg four to the OOI RCA team aboard the R/V Thomas G. Thompson and strong shore support. “I felt well-supported in my first time as Co-Chief, and that helped me step up to the challenge,” she says.

Katie says the coolest part of being on the cruise was working with recent UW graduate Katie Gonzalez. She met the younger Katie when she went to visit her school for an outreach event in the far western reaches of the Olympic Peninsula and later mentored her in the lab for a year. “To see her very confidently and competently prepping the osmotic fluid samplers and then sharing with the ROV pilots what the goals of the installation dive were, and what was needed for this instruments deployment within and active vent site was really cool,” she says.

Katie Bigham grew up as the granddaughter of a commercial fisherman and spent a lot of time on the water, but she didn’t know that oceanography was something people studied until high school, when she interned with an oceanography graduate student at UW. The lab was very welcoming to her, and she attended the lab’s summer barbecues and dissertation defenses in between her work helping to culture Arctic bacteria.

After that experience, Katie initially wanted to study geology at Arizona State University, but she decided to stay closer to home and attend UW instead. When she remembered how welcoming the oceanography lab was, she decided to take oceanography classes, and that’s when things started coming together. Early in her college career, Katie took Dr. Deb Kelley’s hydrothermal vents class and came away from it wanting to see the underwater hot spring environments in person and work with Dr. Kelley and the OOI team.

“Deb bringing me onboard as a VISIONS student and then mentoring me through that process was what helped me know I wanted to stay in oceanography,” Katie explains. “I was really inspired by her research and her work with students, and I’d really like to continue in academia because of her influence. I wouldn’t be doing the things I’m doing without all her support.”

[media-caption path="https://oceanobservatories.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/20210903_100228_01-scaled.jpg" link="#"]VISIONS’21 Leg 4 students and participants. Credit: M. Elend, University of Washington, V21.[/media-caption]Katie is currently pursuing a joint PhD at the Victoria University of Wellington and the National Institutes of Water and Atmospheric Research in New Zealand. She is continuing with deep-sea science, researching the impact of turbidity currents, or underwater landslides, on benthic communities living in submarine canyons. This work builds on some of the work she did for her undergraduate senior thesis mapping megafauna at methane seeps along the RCA. Katie hopes that her research will be helpful for management of marine protected areas in New Zealand and inform about impacts in other marine canyons, such as those on the Cascadia Margin.

Katie returned to Washington from New Zealand during the COVID-19 pandemic. She has been able to continue her writing and data analyses while abroad from an office within the RCA space. Ironically, thanks to the pandemic, she was able to participate in this year’s RCA cruise.

After she obtains her PhD, Katie hopes to continue her research as a postdoc. “I would really like to bring what I’ve learned during my PhD and my experiences with the RCA back together,” she comments. “I’d love to do a postdoc working with RCA data.”

[embed]https://youtu.be/_YOsgNNLOP8[/embed]

Katie Bigham also played an instrumental role in the production of this video that was a project for the VISION’14 class. It was selected as one of the top ten videos in a nationwide contest sponsored by the Florida Center for Ocean Sciences Education Excellence. The video has been viewed by nearly 38,000 student judges in 1,600+ classrooms in 21 countries.

Read More