News

Irminger Sea Array Overcomes Challenging Conditions to Provide Climate Insights

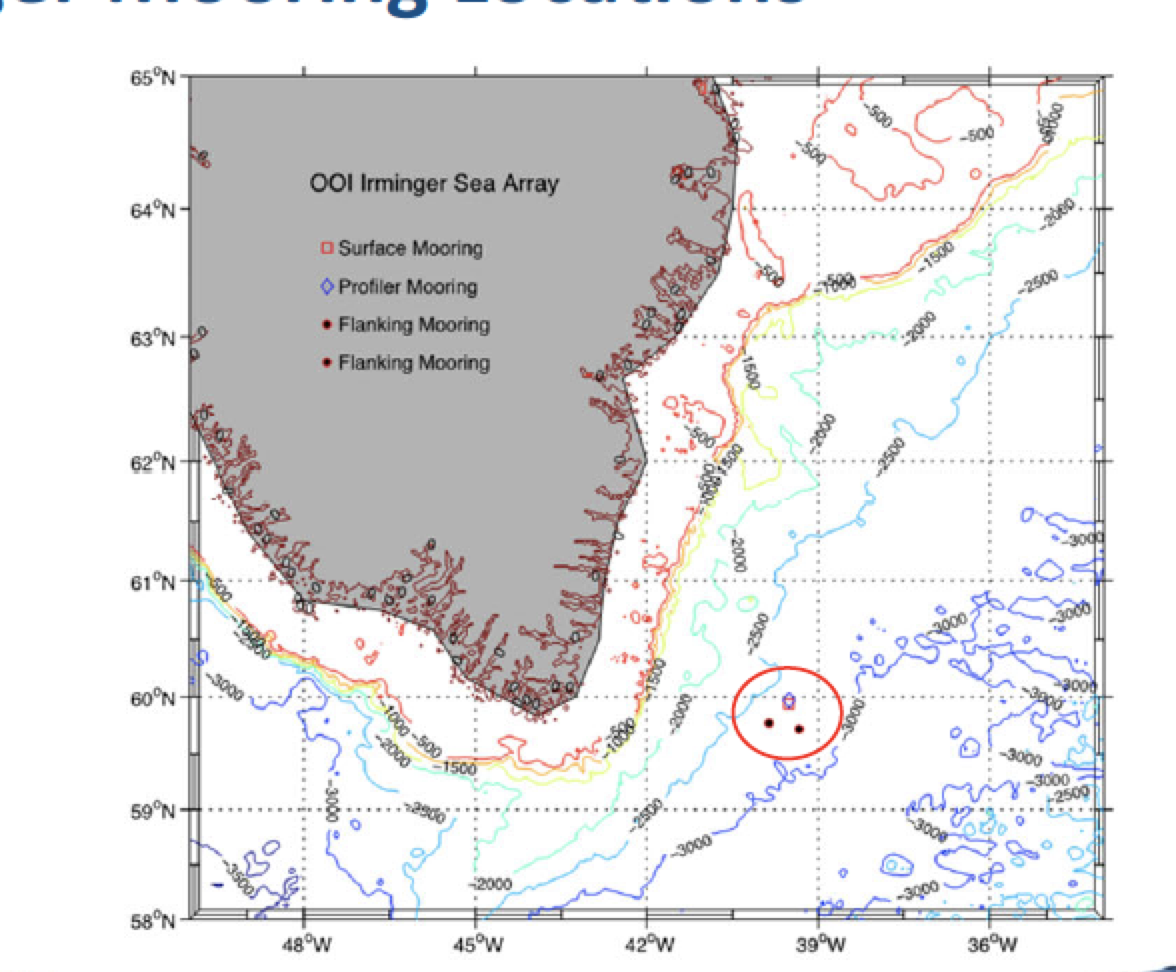

Deployed 140 miles east of the southern tip of Greenland and three miles south of the Arctic Circle, the Irminger Sea surface mooring floats on a cold empty sea named for a Danish naval admiral few people have heard of, in a location that few people could point to on a North Atlantic chart. The Irminger Sea is delineated less by coastlines or geographic basins and more by what is taking place within the deep ocean here, processes only visible with the aid of deep-sea instruments. To oceanographers and climate scientists the region is a confluence of ocean currents where heat carried from the topics gets extracted and cold water sinks into abyss like few other places worldwide and with climate-changing impacts.

Like most high-latitude oceans, storms are frequent and strong. Some storms migrate northeast from the mid-latitudes. Other storms are born here and then mature to impressively violent conditions influenced by the distant high mountains and massive Greenland icecap. Gale-force winds and steep-faced ocean waves spread east over a wide cone from the tip of Cape Farewell. The ice pack around Greenland ejects icebergs, some washing far out to sea where they threaten vessels. Cold air and sea spray build layers of heavy ice on exposed surfaces and instrument sensors. Other oceans can be found with higher waves, some have colder weather, but in few places do storms intensify so quickly, occur as often, and happen in a place so vital to planetary climate. Right where the storm forces are the strongest is also the perfect place for a tower packed with weather instruments.

The Irminger Sea mooring is designed to collect data in this stormy world where meteorological and ocean measurements, especially at the surface, are rare and hard to sustain. The mooring is recovered and a new one put in its place once a year, typically during the short summer month of July when weather conditions are calmest. At more than 4 meters high, the surface mooring tower is heavily instrumented with meteorological sensors and communication antennas, and the surface float is filled with data loggers and redundant computing elements and controllers that collect, store, and transmit data to shore. In total about four tons of floating equipment is anchored to the bottom by a 1.5-mile cable studded with dozens of instruments sampling the deep interior of this sea. To power everything, the buoy float is packed with rechargeable batteries, fueled by solar panels and wind turbines on the buoy tower. Strong winds are usually welcome because they rapidly re-charge the battery packs. Sometimes, however, these can be too much of a good thing.

[media-caption path="/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Irminger-storm-waves.png" link="#"]Storm waves captured by the Irminger Sea tower camera #5 on 2019-03-19 at 09:01:00 UTC during a typical bad weather day. Observations made by the WAVSS instrument (from 09:00 to 09:20 UTC) report significant wave heights around 5 m (16 ft) and maximum heights of 21 m (69 ft). Records from a second accelerometer (MOPAK) report a wave ~5 m high passing at 09:01 UTC, possibly the same one in this photo. About half-a minute later, at 09:01:30 UTC, the MOPAK recorded a wave >20 m (no image).[/media-caption]

A recent storm during October 18-19, 2021, was one such time. The mooring was battered by wind speeds exceeding 35 knots (gale force) for almost 24 hours, with some topping out above 50 knots. Heavy storm seas built up and stacked upon themselves for hours. At the storm’s peak, about one third of the highest waves were above 15 m (49 ft). Picture heaving an 8000 lb. surface mooring 80 ft up and down on a tilt-a-whirl ride that never stops. Waves this high can bring tons of water crashing down. Towering waves were recorded, some reaching up to 20-25 m (66-82 ft), so high they approached the limits of our instruments.

The Irminger Sea continues to test our ability to “weather harden” instruments in stormy parts of the world. From November to March, daylight is fleeting, the sun hovers near the horizon and solar panels trickle out only a few milliamps. For the next few months, many of the instruments in the ocean interior and on the tower will continue to sample, each instrument powered by its own small battery. The Irminger surface mooring will communicate once each day, a tiny burst of data with vital signs, until spring returns and the sun revives the cold battery packs.

[media-caption path="/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Ice-near-mooring-.png" link="#"]Ice near the Irminger Sea mooring 2019-04-02. Credit: @WHOI, Peter Brickley.[/media-caption]

The 2021 storm demonstrated, yet again, the challenges of working in the Irminger Sea. Yet, it also demonstrated the remarkable robustness of the OOI moorings in such extreme conditions. Ocean and meteorological measurements gathered by the Irminger Sea mooring during such storm events are extremely valuable for understanding oceanography and climate processes. Equally important is the invaluable experience gained that will drive continued improvement in the accuracy and durability of instruments deployed under such extreme conditions, with consequent increases in knowledge.

Written by Peter J. Brickley, PhD, Senior Engineer, AOPE Dept., Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution and OOI’s Coastal and Global Scale Nodes Observatory Operations Lead

Read More

Videos of OOI’s Virtual Booth Sessions at AGU

In case you missed any sessions at OOI’s Virtual Booth at the AGU Fall 2021 meeting, you can watch them here at your leisure:

[embed]https://vimeo.com/657572792[/embed] [embed]https://vimeo.com/657554340[/embed] [embed]https://vimeo.com/657568018[/embed] [embed]https://vimeo.com/657540648[/embed] [embed]https://vimeo.com/657477409[/embed] [embed]https://vimeo.com/657874176[/embed] [embed]https://vimeo.com/657995699[/embed] Read MoreRCA Recording Swarm of Earthquakes in Real Time

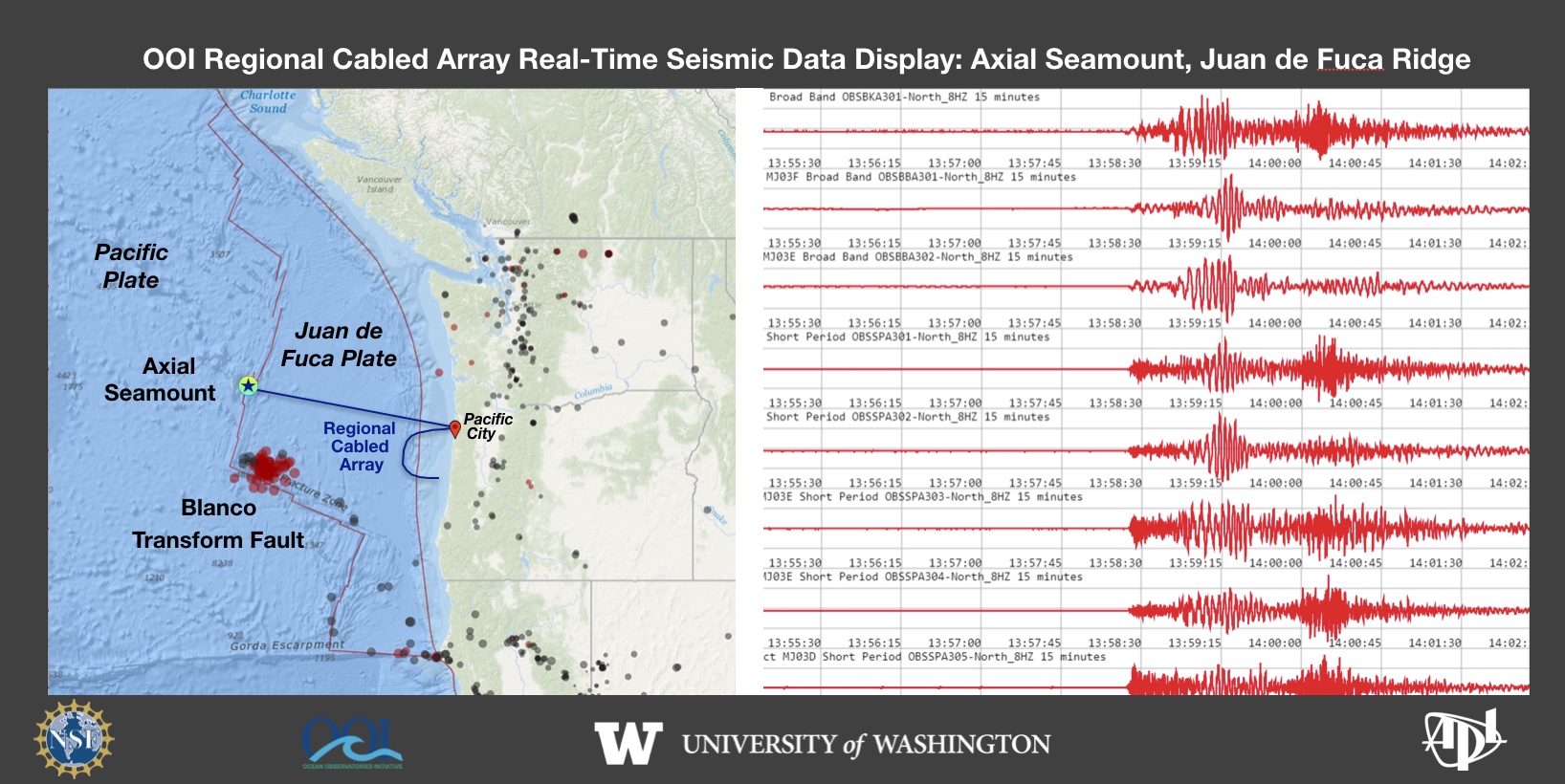

On December 7, 2021 a swarm of earthquakes began on the Blanco Transform Fault, a major plate boundary at the southern end of the Juan de Fuca Plate. The ongoing seismic swarm is being tracked live by the National Science Foundation’s underwater observatory, the Regional Cabled Array (RCA). The RCA is a component of NSF’s Ocean Observatories Initiative and is operated and maintained by the University of Washington. It includes ~900 km of high power and high bandwidth submarine fiber optic cables that stretch from Pacific City, OR out to the most active volcano off the coast “Axial Seamount” that erupted in 1998, 2011 and again in 2015. A second cable heads south along the Cascadia Subduction Zone and turns east along the Cascadia Margin off Newport, OR. Over 150 instruments on the seafloor and on instrumented moorings provide real-time data flow to shore at the speed of light. A suite of seismometers at the summit of Axial Seamount lit up on December 7, 2021 as the seismic swarm began along the Blanco. This live feed was developed by the UW Applied Physics Laboratory.

On December 7, 2021 a swarm of earthquakes began on the Blanco Transform Fault, a major plate boundary at the southern end of the Juan de Fuca Plate. The ongoing seismic swarm is being tracked live by the National Science Foundation’s underwater observatory, the Regional Cabled Array (RCA). The RCA is a component of NSF’s Ocean Observatories Initiative and is operated and maintained by the University of Washington. It includes ~900 km of high power and high bandwidth submarine fiber optic cables that stretch from Pacific City, OR out to the most active volcano off the coast “Axial Seamount” that erupted in 1998, 2011 and again in 2015. A second cable heads south along the Cascadia Subduction Zone and turns east along the Cascadia Margin off Newport, OR. Over 150 instruments on the seafloor and on instrumented moorings provide real-time data flow to shore at the speed of light. A suite of seismometers at the summit of Axial Seamount lit up on December 7, 2021 as the seismic swarm began along the Blanco. This live feed was developed by the UW Applied Physics Laboratory.

Read More

OOI’S AGU Virtual Booth Schedule

OOI is hosting a virtual booth at AGU this year. All events are free and open to those wanting to attend, including those not attending AGU. Register for each event by clicking on the link in the event’s title. We hope to see you virtually at AGU this year! For those attending in person, do check out these OOI-related presentations.

OOI’s Virtual Booth Schedule |

||||

| DATE | TIME | EVENT | DESCRIPTION | PRESENTERS |

| Monday 13-Dec | 3-4 pm CT/4-5 pm ET | MOVING THE PIONEER ARRAY TO THE SOUTHERN MID-ATLANTIC BIGHT | Status of plans, permitting, and projected timeline for relocating the Pioneer Array | Lisa Clough (NSF) Moderator, Al Plueddemann (WHOI), Derek Buffitt (WHOI) |

| Tuesday 14-Dec | 1-2 pm CT/2-3 pm ET | INTRODUCING OOI’S NEW DATA CENTER: CREATIVE WAYS TO USE DATA | How cutting edge techniques to analyze and visualize data are being integrated into research and education | Anthony Koppers (OSU) Moderator, OOI’s New Data Center, Don Setiawan (UW) Interactive Oceans, Wu-Jung Lee (UW) EchoPype, Chris Wingard (OSU) Jupyter Notebooks |

| Tuesday 14-Dec | 3-4 pm CT/4-5 pm ET | OOI AND OSNAP IN THE NORTH ATLANTIC | What we are learning about the changing nature of the North Atlantic | Al Plueddemann (WHOI) Moderator, Nora Fried (NIOZ), Nick Foukal (WHOI), Yao Fu (Georgia Tech), Isabela Le Bras (WHOI) |

| Wednesday 15-Dec | 1-3 pm CT/2-4 pm ET | OOIFB’s DATA SYSTEMS COMMITTEE: USING OOI DATA IN THE CLOUD WITH PANGEO | Be prepared to do science in real time during this hands-on interactive session in the cloud. Participants will need a GitHub account to fully participate. If you don’t have one, it’s a simple process. Once you have a GitHub account, you can experience using real data to resolve a real science question during this workshop. | Tim Crone (LDEO) |

| Wednesday 15-Dec | 3-4 pm CT/4-5 pm ET | WHAT’S NEW IN THE UNDERSEA WORLD OF EARTHQUAKES AND VOLCANOES? | Lead authors of high-impact papers present their findings on Axial Seamount using OOI and other data (i.e. 3D seismics) for an integrated view into this highly active volcano, what their next steps are, how OOI data will play a role, and ideally what tools they would like to have answer their questions. | Deb Kelley (UW) Moderator, Suzanne Carbotte (LDEO), William Chadwick (OSU), William Wilcock (UW) |

| Thursday 16-Dec | 3-4 pm CT/4-5 pm ET | OOIFB LIGHTNING TALKS REDUX | For those who miss the lightning talk presentations during OOIFB’s Town Hall, this is another opportunity to see, hear, and question Lightning Talk presenters | Ed Dever (OSU) Moderator, Lightning talk presenters |

| Friday 17-Dec | 11 am-noon CT/noon-1 pm ET | WHAT’S NEW WITH DATA EXPLORER? | A demonstration of how Data Explorer 1.2 can be used to address science questions using different data types | Jeff Glatstein (WHOI) Moderator, Stacey Buckelew (Axiom), Wendi Ruef, Mike Vardaro (UW), Andrew Reed (WHOI) |

OOI at AGU 2021

[media-caption path="/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/agufront2-scaled-e1603490292321.jpeg" link="#"]The AGU 2021 Fall Meeting is a combination of virtual and in person events. OOI will have a virtual booth with daily activities to join. [/media-caption]

AGU Fall Meeting 2021

The following is a compilation of OOI-related presentations at this year’s fall meeting. If we’ve missed any OOI-related sessions, please contact dtrewcrist@whoi.edu and we will be happy to add them. OOI will have a virtual booth at AGU this year. Interesting programming is being finalized and will be added to this listing once confirmed. Share your AGU news at #AGU2021.

Monday, 13 December 2021

09:07-09:12, Convention Center, Room 223 (Note: all times are in Central time)

OS11A-02 – Overflow Water Pathways in the North Atlantic: New Observations from the OSNAP Program

Susan Lozier, Georgia Institute of Technology, Amy S Bower and Heather H Furey, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, Kimberley Drouin, Duke University, Xiaobiao X, Florida State University, and Sijia Zou, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution.

Tuesday, 14 December 2021

11:15-12:15, Convention Center, Room 395-396

Ocean Observatories Initiative Facilities Board Town Hall

17:00-1900

Posters, Convention Center Poster Hall D-F

B25E-1522 – Synergistic Data Source Approach to Studying Keystone Marine Predators.Elizabeth Ferguson, Ocean Science Analytics. See the poster live.

G25A-0340 – Drift Corrected Pressure Time Series at Axial Seamount, July 2018 to November 2021 – A Progress Report

Glenn S Sasagawa, University of California San Diego and Mark A Zumberge, University of California San Diego.

PP25C-0927 – OOI infrastructure and Experimental Deployments: Preliminary insights from SEA3s deployed from 6 months to 1 year in the North Pacific

Ashley M Burkett, Oklahoma State University and Sarah Keenan, South Dakota School of Mines and Technology.

Wednesday, 15 December 2021

17:00-1900

Posters, Convention Center Poster Hall D-F

V35A – Focused Observations of Ridge Near-Axis Remote and in Situ Investigations: Magmatic, Volcanic, Hydrothermal, and Biological Processes V Poster

Michael R Perfit, Timothy M Shank, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, Jeffrey Karson, Syracuse University, Deborah Kelly, University of Washington, and Kenneth Howard Rubin, University of Hawaii.

Thursday, 16 December 2021

13:45-15:00, Convention Center, el.Lightning Theater VII

V43B – Focused Observations of Ridge Near-Axis Remote and in Situ Investigations: Magmatic, Volcanic, Hydrothermal, and Biological Processes IV eLightning

Michael R Perfit, University of Florida, Timothy M Shank, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, Jeffrey Karson, Syracuse University, Deborah Kelly, University of Washington, and Darin M Schwartz, Boise State University.

14:18-14:21, Convention Center, el.Lightning Theater VII

V43B-07 – Spatial distribution of diffuse discharge at ASHES vent field, Axial Seamount, captured by acoustic imaging

Guangyu Xu, University of Washington, Karen G Bemis, Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey, Darrell Jackson, University of Washington, and Anatoliy N. Ivakin, University of Washington.

V43B-08 – Systematic Shift in Plume Bending Direction at Grotto Vent, Main Endeavour Field, Juan de Fuca Implies Systematic Change in Venting Output along the Endeavour Segment

Karen G Bemis, Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey

17:00-1900

Posters, Convention Center Poster Hall D-F

V45B-0137 – Monitoring at Axial Seamount since its 2015 eruption reveals tightly linked rates of deformation and seismicity

William W. Chadwick Jr, Oregon State University, Scott L Nooner, University of North Carolina at Wilmington, William S D Wilcock, University of Washington, and Jeff W Beeson, Oregon State University.

V45B-0138 – Deformation Models for the 2015-Eruption and Post-Eruption Inflation at Axial Seamount from Repeat AUV Bathymetry

William Hefner, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Scott L Nooner, University of North Carolina at Wilmington, William W. Chadwick Jr., Oregon State University, David W Caress and Jennifer Brophy Paduan, Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute, and Delwayne R Bohnenstiehl, North Carolina State University.

V45B-0139 – Annual and long-term seismic velocity variations at Axial Seamount observed with seismic ambient noise

Michelle Lee, Columbia University, Yen Joe Tan, Chinese University of Hong Kong, Maya Tolstoy, Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory of Columbia University, Felix Waldhauser, Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory of Columbia University, and William S D Wilcock, Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory of Columbia University.

Read More

R/V Oceanus Remembered as a Workhorse of the U.S. Academic Research Fleet

The long service of the R/V Oceanus (1976-2021) came to end on November 21, 2021 as the ship pulled into port after having successfully completed its last interdisciplinary cruise for Oregon State University (OSU). The Oceanus began its 45-year-run of scientific investigations at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI) in 1976. After a major mid-life refit, the ship was transferred to OSU in 2012, and contributed to the Ocean Observatories Initiative (OOI) off both coasts.

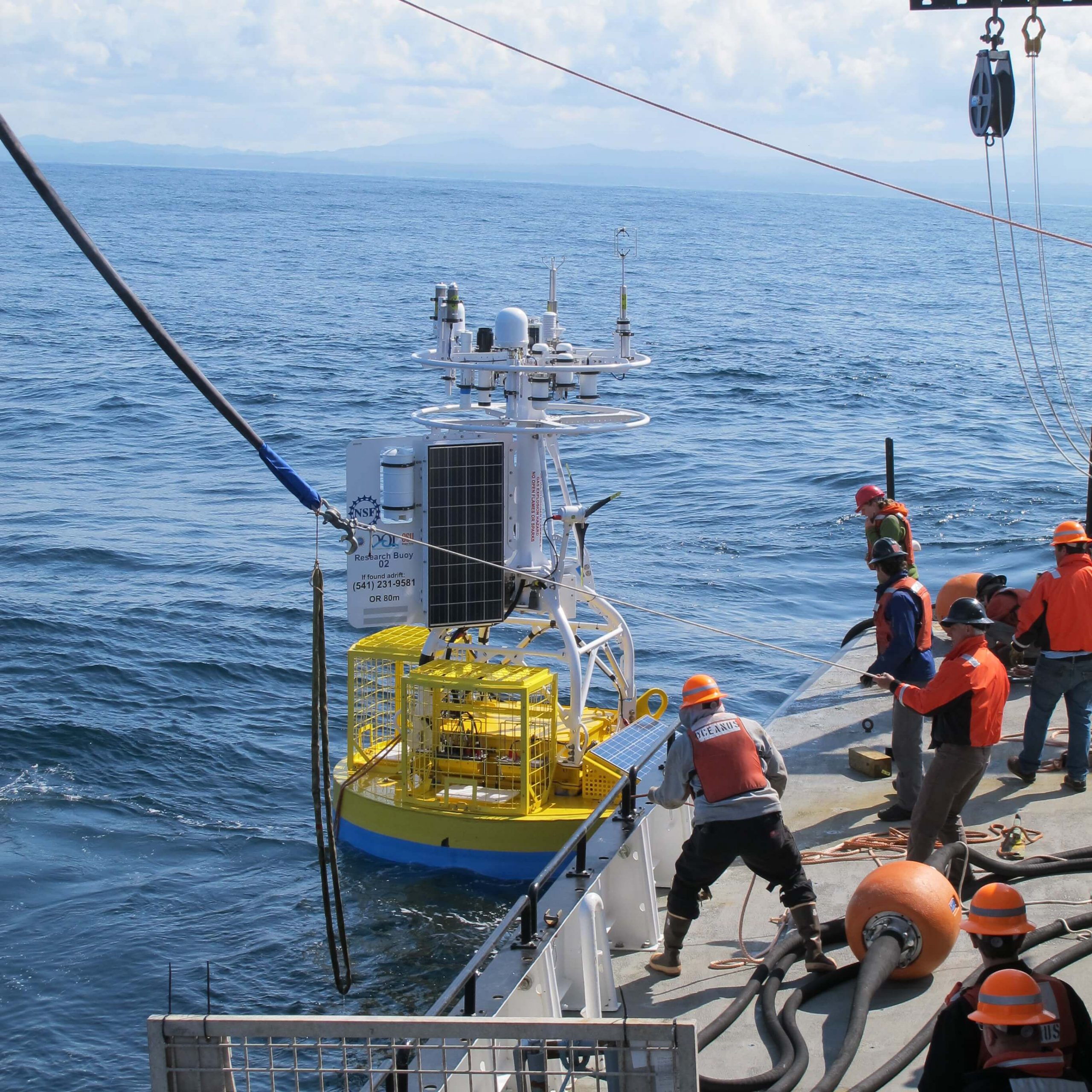

“The Oceanus proved to be a real workhorse for the Academic Research Fleet and also played a pivotal role for the OOI during its initial launch,” said Ed Dever, PI of OOI’s Coastal Endurance Array, who sailed on the ship many times. “While at WHOI, The Oceanus performed some of OOI’s at-sea-mooring test deployments and later the ship was used for the initial deployment of the Coastal Endurance Array off the Oregon coast.”

In spring and fall 2014, after moving to OSU, Oceanus performed the initial deployments of the Oregon and Washington inshore moorings and Washington profiler mooring. The real test for the Oceanus, however, came during 2015, when it was tasked with deploying the full scope of the Endurance Array, including the four large coastal surface moorings at the Oregon and Washington shelf and offshore sites.

Explained Dever, “Thanks to some excellent ship handling, care on the part of the deck crew and a huge assist from some very kind weather, we got the moorings safely in the water using the ship’s crane to deploy the 10,000-pound buoy off the starboard fantail and the heavy lift winch to deploy the 11,000-pound multifunction node (MFN, bottom lander) through the A-frame. The size of the buoys and MFNs meant that Oceanus could only carry one buoy out at a time and the cruise was completed in five legs with some very efficient port stops. By the end of the cruise, it was evident that we would need to move future operations to global and oceans class ships and after one more deployment in fall 2015 (with recoveries carried out on the R/V Thomas G. Thompson), we made that transition.”

[embed]https://youtu.be/pDRagMTDUTk[/embed]After the initial Endurance Array deployments, OOI transitioned to using larger global and oceans class ships needed to recover the bulky coastal surface moorings, with one exception. In spring 2019, with tight schedules on global class ships, UNOLS (University-National Oceanographic Laboratory System charged with ship scheduling) requested that OOI Endurance split the spring mooring recovery and deployment cruise between the R/V Sikuliaq and the R/V Oceanus. The Oceanus ably performed the profiler mooring deployment, anchor recoveries, coastal surface piercing profiler deployments, and glider deployments over five days in April and May 2019.

While not directly working with the OOI, the Oceanus continued to work off Oregon at and around the OOI arrays. Research and student cruises often sampled over the years near OOI’s Endurance and RCA Arrays at the Oregon inshore, shelf, offshore and Hydrate Ridge sites to compare shipboard measurements and OOI time series. This work included CTD profiles, net tows, coring, and sediment trap deployments.

The last Oceanus cruise, in fact, was one such interdisciplinary research cruise led by OSU researcher Clare Reimers, who also served as chief scientist. During its final official outing, the team aboard the Oceanus sampled the outer shelf at the northern end of Heceta Bank, Oregon to help scientists determine any changes that may have occurred to a swath of the margin that was reopened to commercial bottom trawling in 2020 after an 18-year closure. Reimers said, “The R/V Oceanus and crew performed flawlessly, and our science mission was fully completed.”

Added Dever, “What better way to end its long and illustrious career? We at OOI join many others in appreciation of the R/V Oceanus, and the dedication and skills of all who sailed on her and supported ocean science throughout her many years at sea.”

______________________________________________________________________________________

Special thanks to OOI Data Center Project Manager Craig Risien for sharing the GoPro time lapse of the loading of the Oregon Offshore mooring onto the R/V Oceanus in spring 2015.

Read MoreMarine Mammal Operations Aboard R/V Neil Armstrong During Pioneer 17

The Northeast Fisheries Science Center (NEFSC) had the opportunity to participate on leg two of the Pioneer Array research cruise aboard the R/V Neil Armstrong. The dates for the second leg this year were November 7 – 15 2021. This time frame was critical for us because our main asset for assessing right whale distribution, the NOAA (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration)Twin Otter aircraft was scheduled to depart for the Gulf of St. Lawrence Canada, and would not be available. Since 2010 the distribution of the North Atlantic Right whale has changed significantly, and it has become increasingly important to survey more broadly within the range to determine if there are aggregations of right whales in unprotected areas.

Participating scientists from the NEFSC for this cruise were Chris Tremblay and myself, Pete Duley. Chris was brought on for his expertise in acoustics, specifically with the deployment and monitoring of sonobuoys for the detection of North Atlantic Right whales and other large baleen whales. This additional element to our research plan was added to detect right whales in weather when visual observations were not ideal, and to access call types associated with different behaviors from observations with right whales in good visual conditions. Deployment of sonobuoys were conducted with very low or no impact to the mission of the work on the Pioneer array. November 12 was the only day of the entire cruise in which we were unable to conduct visual observations due to the weather. The Northeast U.S Shelf Long Term Ecological Research (NES-LTER) group was conducting a CTD survey across the shelf break and we used this opportunity to make four sonobuoy drops in association with their survey. We are still analyzing the acoustic recordings form the cruise, but at this point feel that they were a valuable addition to the research.

Sonobuoys are launched by hand from the back deck, once permission has been granted by the bridge. The instruments are not meant to be retrieved and can record for up to eight hours. The instruments send information from their hydrophones by VHF transmission (line of sight) to an antenna mounted on one of the upper decks (01), and scuttle themselves after eight hours of recording.

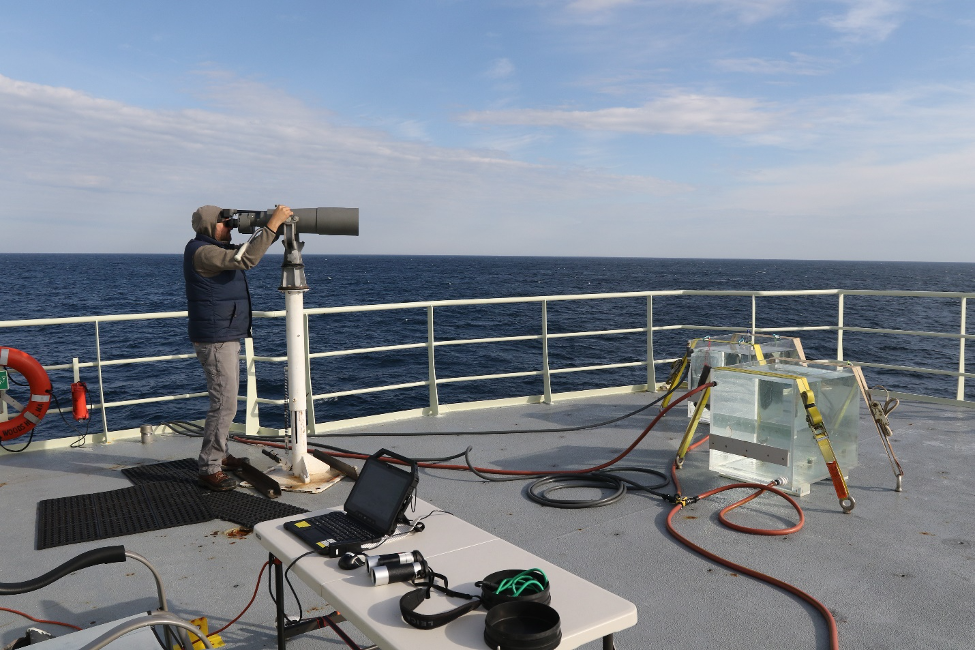

[media-caption path="/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/Bigeyes.png" link="#"]Marine Mammal Observer Chris Tremblay uses Bigeye binoculars to search for right whales during mooring operations by the Pioneer 17 team. Credit: Peter Duley. [/media-caption]

Marine mammal visual operations aboard the Neil Armstrong were conducted from the 01 Deck. Our Bigeye stand would not fit the predrilled holes in the 01 deck and this required Kyle Covert, the ship’s welder, to manufacture some iron fasteners to secure the stand and Bigeye binoculars. This issue was fixed during the staging prior to our departure and worked quite well. The marine mammal observation deck (deck 02) was unavailable to us this year because of Bigeye stand mounting issues. There are plates welded into the deck for the stands, but no predrilled bolt pattern in the deck. The marine mammal deck also has a desk with access to the ship’s SCS (Sea Control Ship) feed, and offers a better vantage point because it is higher. However, even while working in higher sea states we were unaffected by spray from the bow on the 01 deck, and this worked out quite well for this cruise. We brought with us a small desk, some deck chairs, and ratchet straps for securing everything.

The crane on the 01 deck is on the starboard side and caused a slight visual obstruction in panning from 090 to 270 degrees. The location of the Bigeyes aft on the port side, however, provided good visibility nearly to 180 degrees on the port side, which proved useful when stationary during the Pioneer Array mooring deployments and recoveries. We recorded whales aft of the ship during several of these stationary observation periods. Visual observations while underway were conducted from 07:30 to 16:45 and observers rotated from the Bigeyes to the recorder position on the half hour. At the locations where the ship was stationary working on mooring operations for extended periods of time, Chris and I did a scan of the area every 15 minutes. We are still working on analyses of the visual data, and although we did not observe any right whales during the Pioneer 17 cruise we feel that the ship is a great asset for our work and would love for the collaborative effort to continue. Thank you so much for the opportunity to participate this year!

Written by Peter Duley, Fisheries Wildlife Biologist, Northeast Fisheries Science Center

Read MoreWorkshop: OOI Data in Project EDDIE Materials

Project EDDIE and the SERC (Science Education Resource Center at Carleton College) have an exciting workshop coming up that you won’t want to miss! It offers opportunities to build teaching modules using OOI data.

The Project EDDIE Module Development & Community Building Experience will be held online via Zoom as half-day meetings on January 20, 27, and February 10. This workshop will facilitate participants developing teaching modules that pair scientific concepts and quantitative reasoning with teaching with data. The teaching modules follow a tested design rubric developed by Project EDDIE and resulting materials will be published as part of a growing collection of modules.

During the workshop, participants will construct a 1-day module that uses an openly available dataset for a specific ecology, limnology, geology, hydrology, oceanography or environmental science course. Each module will focus on a scientific concept and address a set of quantitative reasoning or analytical skills using large, openly available datasets, such as OOI, following the Project EDDIE module structure. Interactive peer review and module share out meetings following the workshop will help improve developed materials before you pilot them.

Participants will be expected to 1) attend the workshop and develop a module 2)attend one virtual peer review and one module share out and planning session 3) teach and revise their materials, 4) and make revisions from the peer review and an external review before publishing. Final modules will be published online by December 2022. Participants will be provided a $1,500 stipend for completing, testing, and publishing their module.

This workshop also provides special opportunities to:

- Understand how working with large datasets improves quantitative reasoning in students

- Incorporate your module into your syllabus/course schedule and develop an assessment plan

- Meet new people who share similar interests in teaching and working with data

There is no registration cost for attending this meeting. The successful completion and testing of a module includes up to a $1,500 stipend. Successful completion of the modules includes authoring, piloting, revising, and publishing the teaching and supporting materials.

The application deadline for this workshop is November 28, 2021. Apply now. Conveners are actively seeking modules focused on OOI data.

Read More

Student and Early Career Travel Funds Available: Apply Now!

Do you need travel funds to attend and present your OOI research at a conference?

If you need funding to offset conference expenses (registration fees, travel costs, accommodations, etc.), we encourage you to apply. Conference participation can be in-person or virtual. With the Fall AGU and Ocean Science Meetings approaching, we wanted to remind you of this opportunity.

Endurance Array to Provide Hourly Meteorological Data

On 11 October 2021, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA)requested that OOI’s Coastal Endurance Array buoys provide hourly meteorological data to the National Data Buoy Center (NDBC) because a nearby NDBC buoy (46029, Columbia River bar) had gone offline. OOI buoy data are typically telemetered every two hours due to sampling schedule and bandwidth constraints (the actual sampling rate is higher).

Endurance Array team members examined sampling and telemetry schedules for the Endurance offshore coastal surface moorings to see if they could accommodate NOAA’s request. The team concluded that meteorological data from the moorings could be updated hourly while still meeting OOI sampling requirements.

“To help ensure continuity of data to the NDBC, we plan to distribute hourly meteorological data from the Endurance Array Oregon and Washington offshore sites for the duration of the outage at NBDC 46029,” said Edward Dever, lead of the Coastal Endurance Team. “We’re pleased to respond to NOAA’s request and hope these data prove useful to operational weather forecasts and marine safety.” The Oregon and Washington offshore sites have NDBC buoys designations of 46098 and 46100, respectively.

The Endurance Array team will continue to review the performance of the buoys and ensure the updated telemetry schedule does not impact OOI sampling. If data users do experience any impacts from this change in sampling frequency, please contact Jon Fram at Jonathan.Fram@oregonstate.edu.

Read More