Posts Tagged ‘Pioneer Array’

Assessment of OOI Endurance Array pCO2 Data Quality

Given the significant importance of understanding and modeling levels of carbon dioxide in our atmosphere (and its potential sources and sinks), Ocean-Atmosphere Exchange and Global Biogeochemistry and Carbon Cycling are two of the OOI’s primary science themes. We address these themes in part through measurements of the air and surface water partial pressure of carbon dioxide (pCO2). Chris Wingard, the OOI Endurance Array Data Lead, recently completed an in-depth assessment of pCO2 data returned during the first four years of Endurance Array operations. These measurements were made using the Pro-Oceanus CO2-ProTM Atmosphere pCO2 sensor. By measuring the partial pressure of CO2 gas in both the air and surface water, researchers can estimate estimate surface flux of CO2 using data from this instrument.

Wingard developed a protocol based on cross-comparisons of overlapping deployments of this sensor, comparing these with independent shipboard pCO2 measurements (including CTD samples and samples taken underway using flow-thru systems), and externally sourced air and surface water pCO2 measurements (e.g. from the LDEO Underway Database). This array of sampling techniques served to confirm the quality and scientific applicability of the Endurance Array pCO2 measurements.

He reported the results of this assessment at a poster session at the recent Ocean Sciences 2020 meeting held this past February in San Diego, CA. The protocol is largely applicable to the same suite of measurements made using the Pro-Oceanus sensor on moorings deployed in the OOI Pioneer, Irminger Sea, Southern Ocean, and Argentine Basin Global Arrays. The MATLAB code and data used to download, process, merge, and cross-compare the data used in this assessment are available online for use.

Both the air and surface water measurements and the flux estimates used in this assessment are available through the OOI Data Portal. Endurance Array air and surface water pCO2 measurements are made at four locations distributed across the Oregon and Washington shelf and slope within the northern California Current Marine Ecosystem.

Other sources of Endurance Array-specific data include the most recent 60 days of the Endurance Array’s air and surface water pCO2 data are available on the NANOOS Visualization System (NVS) and the Global Ocean Acidification Observing System Data Portal (GOA-ON).

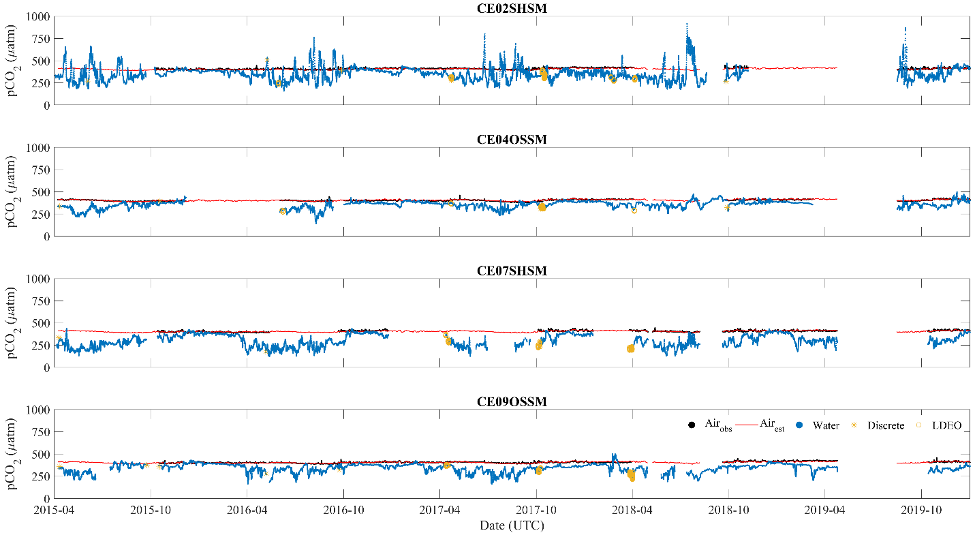

Figure 1: Surface water (•) and air pCO2 (•, observed and —, array average) measurements from 2015-04-01 through 2019-12-31 for the four moorings. The plots also show the distribution of discrete sample (*) and LDEO V2018 (O) data that coincide with each mooring. The data plotted have had human-in-the-loop (HITL) QC flags applied to remove points marked as suspect or failed. Beyond smoothing the data records and the estimation of an array averaged air pCO2 (—), no further corrections were applied to the data. Note the high degree of variability during the summer months in the surface water pCO2 measurements for CE02SHSM, which are similar to other observations made on the Oregon Shelf (Evans et al., 2011).

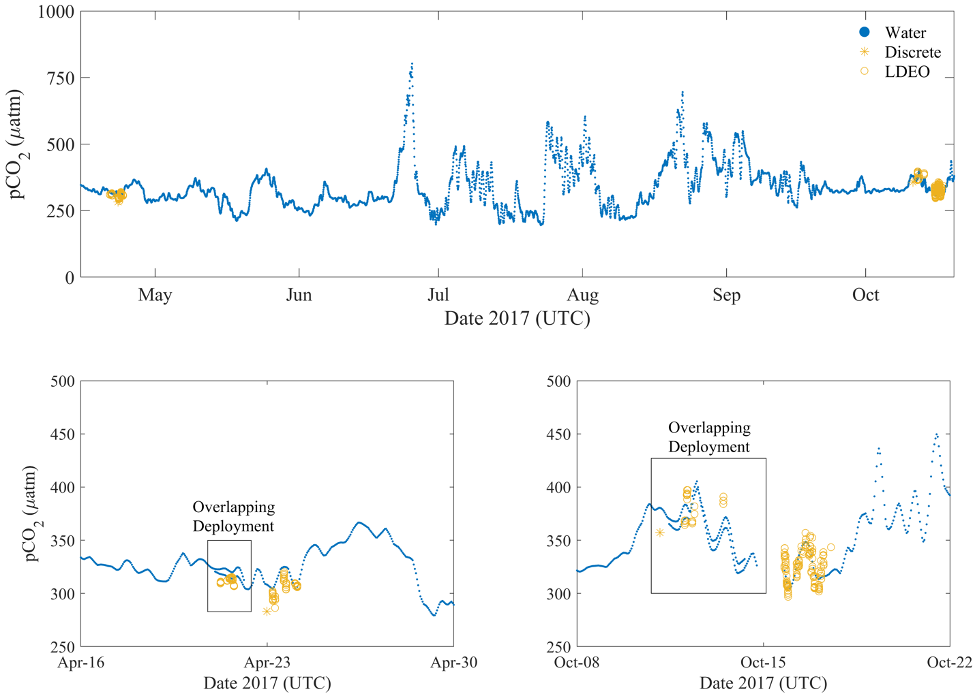

Figure 2: Focused view (upper panel) of the Spring 2017 deployment (#5) of CE02SHSM showing the observed offsets between the surface water pCO2 measurements (•) and the discrete samples (*) and LDEO V2018 (O). Detailed views in the lower two panels, provide a better picture of the observed offsets during the periods of over-lapping deployments; between deployments 4 and 5 (lower left) and deployments 5 and 6 (lower right). Prior to using the OOI pCO2A data, users are strongly encouraged to conduct such cross-comparisons. The independent measurements obtained by the separate systems, and the close agreement between them, provide measures of confidence in the accuracy and applicability of the data.

Read MoreUNOLS Extends Guidance to Suspend Cruises through 1 July 2020

The University-National Oceanographic Laboratory System (UNOLS), which coordinates oceanographic ships’ schedules, recommended on 17 March 2020 that cruise activities be paused for 30 days due to the COVID-19 pandemic. On 30 March UNOLS extended its guidance to suspend research cruises to July 1 2020. This action is designed to protect the health and safety of the crews and scientific parties.

The planned spring operation and maintenance (O&M) cruise to the Endurance Array in March was affected by the original 30-day guidance. The upcoming O&M cruises for the Pioneer, Irminger, and Papa Arrays aboard R/V Neil Armstrong and R/V Sikuliaq are impacted by this latest guidance.

The OOI is working with UNOLS and ship operators to find potential opportunities to complete the scheduled cruises and conduct needed maintenance on the arrays. In the meantime, there’s been no interruption in OOI data. OOI data continue to be collected and made available for use by the scientific and educational communities.

Read MoreFifteen Findings in 15 minutes

“Just like lightning,” in one-minute presentations, 15 scientists shared amazing ways they are using OOI data in scientific investigations and in the classroom. This round of lightning talks capped the Ocean Observatories Initiative Facility Board’s (OOIFB) Town Hall at the 2020 Ocean Sciences Meeting on 20 February, demonstrating the multiple and creative ways OOI data are being used to answer key science questions in a changing environment.

The presentations ranged from how students are using real-life and real-time OOI data to advance their understanding of scientific principles to how researchers are using OOI data to identify the presence of marine life by sound to how modelers are making OOI data more accessible and useable.

“We were simply thrilled by the depth, breadth, and range of applications of OOI data shown during this lightning round,” Kendra Daly, chair of the OOIFB. “We were pleased so many presenters were willing to accept the challenge. This enthusiastic response clearly shows that OOI data are being used to help answer important science questions.”

Brief summaries of the talks are presented below.

Advancing science

Isabela Le Bras, Scripps Institution of Oceanography, reported on a recent article in Geophysical Research Letters, where she and her colleagues describe how they used data from the Irminger Sea Array moorings (2014–2016) to identify two water masses formed by convection and showing that they have different rates of export in the western boundary current. Upper Irminger Sea Intermediate Water appears to form near the boundary current and is exported rapidly within three months of its formation. Deep Irminger Sea Intermediate Water forms in the basin interior and is exported on longer time scales. The subduction of these waters into the boundary current is consistent with an eddy transport mechanism. The eddy transport process is more effective for the waters cooled near the boundary current, implying that cooling near boundary currents may be more important for the climate than has been appreciated to date.

Since 2017, Clare Reimers and Kristen Fogaren, Oregon State University, have been working to assess seasonal variability in benthic oxygen consumption and the contribution of benthic respiration to the development of hypoxic conditions in the northern California Current, using time series data from the OOI Endurance Array. Reimers and Fogaren measured benthic oxygen consumption rates using in situ eddy covariation techniques and ex situ core incubations, during a series of ten cruises that allowed sampling near the Endurance Oregon Shelf and Inshore stations, in all seasons. During these cruises, the researchers used real-time data provided by the Endurance Array to optimize the settings for their eddy covariance deployments. They are now examining property-relationships in discrete bottom water samples collected during the cruises and using data from OOI assets to help separate influences of mixing and biochemical processes in the water column and sediments. The researchers are also synthesizing benthic flux measurements and placing these rates in the context of cross-shelf glider measurements and benthic node time series.

Adrienne Silver, University of Massachusetts Dartmouth provided details about how she is using Pioneer Array data to learn more about the influence of warm core rings on Shelf break circulation. Results from a 40-year Warm Core Ring census show a regime shift in warm core ring formation at 2000, with the number of rings doubling from an average of 18 rings per year (during 1980-1999) to 33 rings per year (during 2000-2019). This regime shift creates a large increase in the amount of warm salty water being transported northward toward the shelf from the Gulf Stream. The preferred pathway of these rings, or the Ring Corridor seem to indicate their proximity to the shelf break and the Pioneer array during their lifetime. The goal of Silver’s project is to understand how these warm core rings affect the shelf break exchange while traveling along the shelf. A large focus of the study will be on the salinity intrusion events which might be sourced from these warm core rings.

Liz Ferguson, CEO and founder of Ocean Science Analytics, is using data from OOI’s Coastal Endurance and Regional Cabled Arrays to determine the variables that are most useful for assessing the ecosystem of this region and obtaining baseline information on marine mammal acoustic presence for use in monitoring. Using long term physical and biological data provided by these arrays, Ferguson is assessing long-standing shifts in the ecology of this coastal and offshore environment by associating physical oceanographic variables with the vocal presence of marine mammals using the broadband hydrophone data. Temporal changes in the occurrence of marine mammal species such as killer whales, sperm whales and dolphins can be used as an indicator of ecosystem shifts over time. She is analyzing passive acoustic data provided by the OOI arrays to determine the presence of vocally active marine mammal species, identify their spatial and temporal use of these sites, and combining this information with the physical oceanographic variables to assess the ecological characteristics associated with marine mammal occurrence.

Sam Urmy of the Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute (MBARI) also is using OOI acoustical data in his research. Using an upward-looking echosounder and a high-frequency hydrophone at MBARI’s Monterey Accelerated Research System, Urmy showed how small animals in the epipelagic and mesopelagic altered their behavior in response to predators. These responses included abrupt dives during bouts of foraging by dolphins, changes in depth to avoid predatory fish schools, and dramatic alterations to daily vertical migratory behavior. Continual observations of the mesopelagic with active and passive acoustics are revealing several dynamic predator-prey interactions in an ecosystem that is typically thought of as relatively slow and static.

Veronica Tamsitt of the University of New South Wales used the OOI’s Southern Ocean mooring and the Southern Ocean Flux Site (SOFS, in the Southeast Indian) to study the Sub Antarctic Mode water (SAMW) formation. Tamsitt’s and her colleagues findings were reported in the Journal of Climate in March 2020. Using data from the two mooring locations, the researchers were able to compare and contrast characteristics and variability of air-sea heat fluxes, mixed-layer depths, and SAMW formation. The researchers found that inter mixed-layer depth anomalies tended to be intermittent at the two moorings, where anomalously deep mixed layers were associated with anomalous advection of cold air from the south, and conversely shallow mixed layers correspond to warm air from the north. Both the winter heat flux and mixed-layer depth anomalies, however, showed a complex spatial pattern, with both positive and negative anomalies in both the Indian and Pacific basins that Tasmitt and colleagues relate to the leading modes of climate variability in the Southern Ocean.

Editor’s note: The Southern Ocean Array was decommissioned in January 2020. Its data, however, are still available for use by researchers, students, and the public.

Bringing OOI data into the classroom

Sage Lichtenwalner, Department of Marine and Coastal Sciences at Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey reported on the progress of the Ocean Data Labs Project. This project is a Rutgers-led effort to build a “Community of Practice” to tap into the firehose of OOI ocean data to support undergraduate education. To date, the project has hosted four “development” workshops that introduced participants to the OOI, conducted data processing with Python notebooks, and shared effective teaching strategies, in addition to a series of introductory workshops and webinars. As part of the development workshops, 56 university, college, and community college faculty designed 19 new “Data Explorations,” featuring web-based interactive “widgets” that allow students to interact with pre-selected data from the OOI. The project also sponsors a series of webinars, a fellowship program, and is compiling a library of resources (including coding notebooks, datasets, and case studies in teaching) to help the community.

Cheryl Greengrove, University of Washington Tacoma, summarized an article in the March issue of Oceanography that she and colleagues from across the United States wrote detailing ways to integrate OOI data into the undergraduate curriculum. The wealth of freely-accessible data provided by OOI platforms, many of which can be viewed in real or near-real time, provides an opportunity to bring these authentic data into undergraduate classrooms. The TOS article highlights existing educational resources derived from OOI data that are ready for other educators to incorporate into their own classrooms, as well as presents opportunities for new resources to be developed by the community. Examples of undergraduate introductory oceanography OOI data-based lessons using existing interactive online data widgets with curated OOI data on primary productivity, salinity, and tectonics and seamounts are presented, as well as ways to use OOI data to engage students in undergraduate research. The authors provide a synthesis of existing tools and resources as a practical how-to guide to support new resource development and invite other educators to develop and implement new educational resources based on OOI data.

Matthew Iacchei, Hawaiʻi Pacific University, presented how he has been integrating OOI data explorations to supplement his upper division oceanography lecture and labs with real data from around the world. Last semester, he had students explore patterns of dissolved oxygen and impacts of anoxia at the coastal endurance array in Oregon and compare that data to dissolved oxygen data the students collected in Kāneʻohe Bay, Hawaiʻi. This semester, students are working through two exercises with OOI data as part of their primary productivity lab (perfect, as it is now online!). Students will compare vertical profiles from Hawaiʻi with seasonal variations across the world, and will compare latitudinal drivers of primary production using data from a time-series from the Southern Ocean Array.

Strengthening OOI data usability

Wu-Jung Lee, a senior oceanographer at the Applied Physics Laboratory, University of Washington, is using data collected by the OOI to develop new methodologies for analyzing long-term ocean sonar time series. In a project funded by the National Science Foundation, she and her colleagues show that unsupervised matrix decomposition techniques are effective in discovering dominant patterns from large volumes of data, which can be used to describe changes in the sonar observation. Their preliminary analysis also show that the summaries provided by these methods facilitate direct comparison and interpretation with other ocean environmental parameters concurrently recorded by the OOI. A parallel effort that spun out of this project is an open-source software package echopype, which was created to enable interoperable and scalable processing of biological information from ocean sonar data.

As part of the Rutgers Ocean Modeling Group, in conjunction with University of California Santa Cruz, John Wilkin and Elias Hunter are delivering a high-resolution data assimilative ocean model analysis of the environs of the Pioneer Coastal Array, including a systematic evaluation of the information content of different elements of the observing network. The project uses the Regional Ocean Modeling System with 4-Dimensional Variational data assimilation. To produce a comprehensive multi-year (2014-2018) analysis required them to assimilate all available Pioneer CTD data, with quality checks, in a rolling sequence of data assimilation analysis intervals. They used three days of data in each analysis, which required queries to with a time range constraint and relevant platform (i.e. glider, profiler, fixed sensor), migrating all Pioneer CTD data (wire following profilers, gliders, fixed sensors, plus ADCP velocity) to an ERDDAP server. The simple graphing capabilities in ERDDAP allow quick browsing of the data to trace quality control or availability issues, and ERDDAP provides a robust back-end to other web services to create more sophisticated graphical views, or time series analysis. Using the ERDDAP Slide Sorter tool, they operate a quick look Control Panel to monitor the data availability and quality.

Mitchell Scott and colleagues Aaron Marburg and Bhuvan Malladihalli Shashidhara at the University of Washington, are studying how to segment macrofauna from the background environment using OOI data from the Regional Cabled Axial Seamount Array. Their long-term goal is to use an automated approach to study species variation over time, and against other environmental factors. Their initial step focuses specifically on scale worms, which are very camouflaged, making them difficult to detect. To address this, the researchers initially used a deep learning model, called U-Net, to detect and localize the scale worm locations within an image. To address the high rate of false positives using this model, they added an additional classifier (a VGG-16 model) to verify the presence of scaleworms. This combined, applied approach proved feasible for scale worm detection and localization. Yet because the environment of the Axial Seamount is so dynamic due to the growth and decay of chimneys at the site and resulting changes in bacteria and macrofauna present, they found the performance of the model decreased over time.

Weifeng (Gordon) Zhang of Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution has been using Pioneer Array data to understand the physical processes occurring at the Mid-Atlantic Bight shelf break, including the intrusion of Gulf Stream warm-core ring water onto the shelf and the ring-induced subduction of the biologically productive shelf water into the slope sea. His findings were reported in a Geophysical Research Letters paper where data from the Pioneer Array moorings and gliders demonstrated the anomalous intrusion of the warm and salty ring water onto the shelf and revealed the subsurface structure of the intrusion. Zhang also shared findings reported in the Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans where data from the Pioneer Array showed a distinct pattern of relatively cold and fresh shelf water going underneath the intruding ring water. These results show the subduction of the shelf water into the slope sea and a pathway of shelf water exiting the shelf. In both instances, Zhang and his colleagues used computer modeling to study the dynamics of these water masses. These two studies together suggest that shelf break processes are complex and require more studies in the region.

Hilary Palevsky of Boston College presented results from an ongoing project funded by the National Science Foundation’s Chemical Oceanography program, using biogeochemical data from the OOI Irminger Sea Array. Analysis of dissolved oxygen data on OOI Irminger Sea gliders and moorings from 2014-2016 showed the importance of biogeochemical data collected over the full seasonal cycle and throughout the entire water column, due to the influence of subsurface respiration and deep winter convection on biological carbon sequestration. The OOI Irminger Sea array is the first source of such full-depth year-round data in the subpolar North Atlantic. To quantitatively evaluate the annual rate of carbon sequestration by the biological pump and the role of deep winter convection, Palevsky and colleague David Nicholson of the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution collaborated with OOI to improve the calibration of oxygen data at the Irminger Sea array by modifying the configuration of glider oxygen sensors to enable calibration in air each time the glider surfaces, which improves the accuracy and utility of the data collected both from gliders and from moorings. Palevsky presented preliminary results demonstrating successful glider air calibration at the Irminger array in 2018-2019 as well as work by student Lucy Wanzer, Wellesley College, demonstrating the importance of well-calibrated oxygen time series data to determine interannual variability in rates of subsurface respiration and deep winter ventilation in the Irminger Sea.

Read More

Endurance Cruise Delayed by COVID-19

The spring 2020 OOI Endurance Operations and Management (O&M) turn cruise has been delayed for at least 30 days due to travel and personnel restrictions imposed to stem the spread of the virus COVID-19.

The 16-day cruise was set to depart on 31 March from Newport, Oregon aboard the R/V Sikuliaq to service the array off the Oregon and Washington coasts. The R/V Sikuliaq is part of the US academic research fleet managed by UNOLS (the University-National Oceanographic Laboratory System). UNOLS imposed a 30-day suspension in fleet operations on 13 March to help ensure the safety of the ship’s crew and science party and to mitigate the risk of virus spread. Rescheduling of activities will commence once the situation stabilizes and UNOLS sees a path forward to re-start research vessel operations safely.

Upcoming O&M cruises for the Pioneer, Irminger, and Papa Arrays also are scheduled aboard UNOLS vessels (R/V Neil Armstrong and R/V Sikuliaq). These cruises fall outside of the UNOLS current 30-day suspension so cruise preparation continues.

We do not anticipate that cruise schedule changes will affect the collection nor dissemination of OOI data, which will continue to be available for users here.

Read More

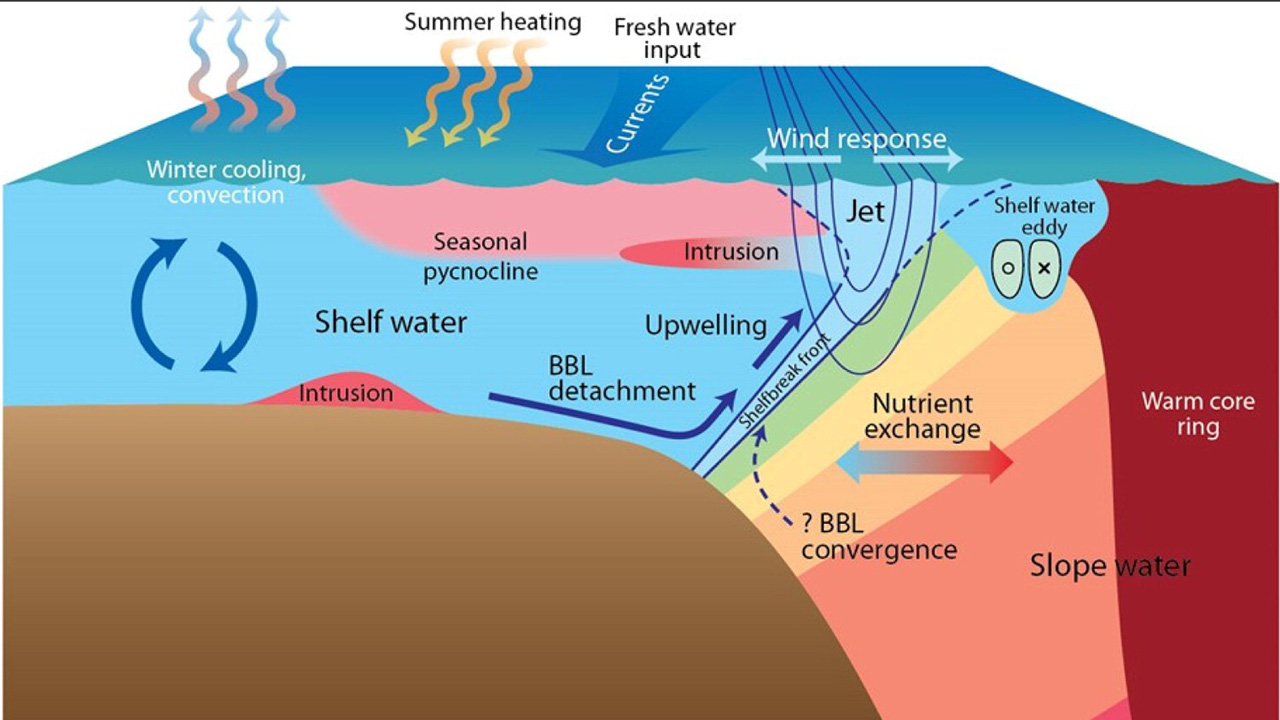

Pioneer Array Design: Building on the known to explore the unknown

The location of the Ocean Observatories Initiative Pioneer Array has been ideal for understanding recent, unprecedented changes in temperature and ocean properties on the continental shelf and slope off the coast of New England, coincident with an increase in warm core rings at a time when the Gulf Stream has grown increasingly unstable. That’s the conclusion of a review paper published last month in the Journal of Operational Oceanography.

The paper, written by Glen Gawarkiewicz and Al Plueddemann of Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, details how the components and location of the array were determined and how the data gathered there has changed scientific questions being asked in this critical region. The array also provides a unique observatory model that can be applied in other shelf break regions across the world.

“We already knew a fair bit about what was happening in the region, but what we’re seeing now isn’t what we expected,” said Plueddemann. “Fortunately, the array was designed and constructed in such a way that we were ready for just about anything.”

The shelf break front stretches along the U.S. Northeast Coast from Georges Bank to Cape Hatteras, dividing cooler, fresher waters of the coast and continental shelf from warm, saltier waters of the slope. It is a complex, productive, and constantly changing area, driven by the interaction of winds, currents, and offshore rings.

Prior to the Pioneer Array, data from the shelf break came primarily from stationary moored instruments or from short-term, mobile observations provided by ocean gliders and towed shipboard systems. In designing the Pioneer Array, scientists and engineers working with the NSF-funded Ocean Observatories Initiative integrated moorings, gliders and propeller-driven AUVs to provide a long-term, multi-dimensional data set that blends the advantages of multiple observing technologies. This is particularly important as ocean processes occurring at the shelf break occur on a variety of space and time scales.

Gawarkiewicz and Plueddemann point out that in addition to enabling new scientific discovery, data from the Pioneer Array has the potential for real-time applications to help track and forecast hurricanes and winter storms, improve search-and-rescue operations, and the siting and operation of off-shore wind installations.

Since becoming operational in 2016, the Pioneer Array has gathered near-continuous data across a 24,000 square-kilometer swath of the shelf break region. By combining moorings, gliders, and AUVs, the array has provided the scientific community with high-resolution observations across space and time, which are unprecedented in their scope and detail and are also freely available on the Ocean Observatories Initiative data portal.

“We haven’t even scratched the surface yet,” said Plueddemann. “There’s still lots of potential to mine in the Pioneer Array data.”

The Ocean Observatories Initiative (OOI) is a long-term infrastructure project funded by the National Science Foundation to gather physical, chemical, and biological data from the ocean, atmosphere, and seafloor and to deliver that data on demand and in near real-time online. The program includes fixed instruments and autonomous underwater vehicles deployed at key locations off in U.S. coastal waters and in the open ocean. The OOI currently maintains arrays off the Northeast and Northwest coasts of the U.S., the Irminger Sea southeast of Greenland, and at Station Papa in the Gulf of Alaska, as well as a seafloor cabled array off the coast of Oregon. Data from the arrays help researchers address questions ranging from rapidly changing weather events to long-term climate change and from air-sea interaction to sea floor processes. OOI is managed by the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI) and implemented by WHOI, the University of Washington, Oregon State University, and Rutgers, the State University of New Jersey.

Read More

WHOI’s “Life at the Edge” video captures the Pioneer Array

What makes the shelf break front such a productive and diverse part of the Northwest Atlantic Ocean? To find out, a group of scientists on the research vessel Neil Armstrong spent two weeks at sea in 2018 as part of a three-year project funded by the National Science Foundation. During this cruise researchers were able to utilize the near-real-time data from the OOI Pioneer Array to help direct their sampling efforts.

Read MoreEarly Career Highlight – Cassandra Alexander – Oceanographic research experiences at a landlocked undergraduate teaching university

“The Ocean Observatories Initiative really opens it up for students to be able to do a lot of different things with the ocean data,” says Alexander. “As long as you can think of it, you can explore it.”

Read MoreEarly Career Highlight – Kanieka Neal – From Maryland to Massachusetts, pushing her chemistry comfort zone

“The OOI is a great resource for students,” says Neal. “It’s not too time consuming, comes right to your inbox, and is very organized so I could pick it up really quickly. It’s amazing that the data are right at your fingertips; you can just go in and get it.”

Read MoreThe Economist – Gliders on the storm

(From The Economist / Technology Quarterly)

From sharks to ice shelves, monsoons to volcanoes, the scope of ocean monitoring is widening.

IN NOVEMBER 2016 a large crack appeared in the Larsen C ice shelf off Antarctica (pictured). By July 2017 a chunk a quarter of the size of Wales, weighing one trillion tonnes, broke off from the main body of the shelf and started drifting away into the Southern Ocean. The shelf is already floating, so even such a large iceberg detaching itself did not affect sea levels. But Larsen C buttresses a much larger mass of ice that sits upon the Antarctic continent. If it breaks up completely, as its two smaller siblings (Larsens A and B) have done over the past 20 years, that ice on shore could flow much more easily into the ocean. If it did so—and scientists believe it would—that ice alone could account for 10cm of sea-level rise, more than half of the total rise seen in the 20th century.

The dynamics of the process, known as calving, that causes a shelf to break up are obscure. That, however, may soon change. Ocean Infinity, a marine-survey firm based in Texas, is due to send two autonomous drones under the Larsen C shelf in 2019, the first subglacial survey of its kind. “It is probably the least accessible and least explored area on the globe,” says Julian Dowdeswell, a glaciologist at the University of Cambridge who will lead the scientific side of the project.

The drones set to explore Larsen C look like 6-metre orange cigars and are made by Kongsberg—the same Norwegian firm that runs the new open-ocean fish farms. Called Hugin, after one of the ravens who flew around the world gathering information for Odin, a Norse god, the drones are designed to cruise precisely planned routes to investigate specific objects people already know about, such as oil pipelines, or to find things that they care about, such as missing planes. With lithium-ion-battery systems about as big as those found in a Tesla saloon the drones can travel at four knots for 60 hours on a charge, which gives them a range of about 400km. Their sensors will measure how the temperature of the water varies. Their sonar—which in this case, unusually, looks upwards—will measure the roughness of the bottom of the ice. Both variables are crucial in assessing how fast the ice shelf is breaking up, says Dr Dowdeswell.

The ability to see bits of the ocean, and things which it contains, that were previously invisible does not just matter to miners and submariners. It matters to scientists, environmentalists and fisheries managers. It helps them understand the changing Earth, predict the weather—including its dangerous extremes—and maintain fish stocks and protect other wildlife. Drones of all shapes and sizes are hoping to provide far more such information than has ever been available before.

That’s why it’s hotter under the water

To this end Amala Mahadevan of Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute (WHOI) in Massachusetts, has been working with the Indian weather agencies to install a string of sensors hanging down off a buoy in the northern end of the Bay of Bengal.

A large bank of similar buoys called the Pioneer Array has been showing oceanographers things they have not seen before in the two years it has been operating off the coast of New England. The array is part of the Ocean Observatories Initiative (OOI) funded by America’s National Science Foundation. It is providing a three-dimensional picture of changes to the Gulf Stream, which is pushing as much as 100km closer to the shore than it used to. “Fishermen are catching Gulf Stream fish 100km in from the continental shelf,” says Glen Gawarkiewicz of WHOI. These data make local weather forecasting better.

Three other lines of buoys and floats have recently been installed across the Atlantic in order to understand the transfer of deep water from the North Atlantic southwards, a flow which is fundamental to the dynamics of all the world’s oceans, and which may falter in a warmer climate.

Another part of the OOI is the Cabled Array off the coast of Oregon. Its sensors, which span one of the smallest of the world’s tectonic plates, the Juan de Fuca plate, are connected by 900km of fibre-optic cable and powered by electricity cables that run out from the shore. The array is designed to gather data which will help understand the connections between the plate’s volcanic activity and the biological and oceanographic processes above it.

A set of sensors off Japan takes a much more practical interest in plate tectonics. The Dense Oceanfloor Network System for Earthquakes and Tsunamis (DONET) consists of over 50 sea-floor observing stations, each housing pressure sensors which show whether the sea floor is rising or falling, as well as seismometers which measure the direct movement caused by an earthquake. When the plates shift and the sea floor trembles, they can send signals racing back to shore at the speed of light in glass, beating the slower progress of the seismic waves through the Earth’s crust, to give people a few valuable extra seconds of warning. Better measuring of climate can save lives over decades; prompt measurement of earthquakes can save them in an instant.

Read More