Science Highlights

Delineating Biochemical Processes in the Northern California Upwelling System

Excerpted from the OOI Quarterly Report, 2022.

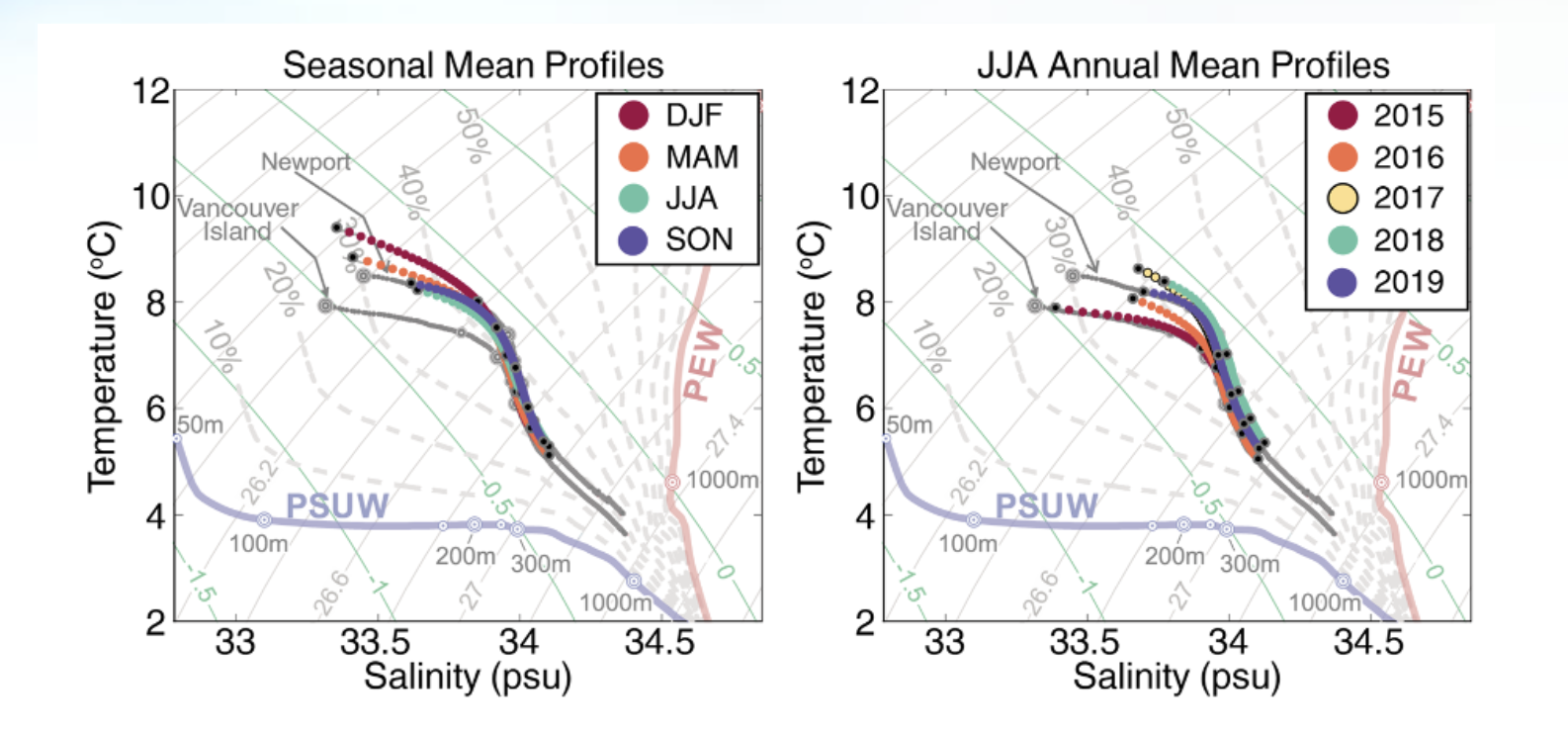

[media-caption path="/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/Endurance-Array-Science-Highlight.png" link="#"]Figure 19: Regional T/S variability at the Washington offshore profiling mooring. The end member Pacific Subarctic Upper Water (PSUW) and Pacific Equatorial Water (PEW) masses are indicated on each plot at the left and right respectively. T/S at the mooring is a mixture of PSUW and PEW. The left plot shows the seasonal variability. The right plot shows interannual variability in summer. Interannual variability from 100-250m exceeds seasonal variability. In 2015, T/S at the mooring is closer in character to climatological averages at Vancouver Island, BC while in 2018, T/S at the mooring is similar to that south of Newport, OR. Figure from Risien et al. adapted from Thomson and Krassovski (2010).[/media-caption]

Risien et al. (2020) presented over five years of observations from the OOI Washington offshore profiling mooring. First deployed in 2014, the Washington offshore profiler mooring is on the continental slope about 65 km west of Westport, WA. Its wire Following Profiler samples the water column from 30 m depth down to 500 m, ascending and descending three to four times per day. Traveling at approximately 25 cm/s, the profiler carries physical (temperature, salinity, pressure, and velocity) and biochemical (photosynthetically active radiation, chlorophyll, colored dissolved organic matter fluorescence, optical backscatter, and dissolved oxygen) sensors. The data presented included more than 12,000 profiles. These data were processed using a newly developed Matlab toolbox.

The observations resolve biochemical processes such as carbon export and dissolved oxygen variability in the deep source waters of the Northern California Upwelling System. Within the Northern California Current System, over the slope there is a large-scale north-south variation in temperature and salinity (T/S). Regional T/S variability can be understood as a mixing between warmer, more saline Pacific Equatorial Water (PEW) to the south, and fresher, colder Pacific Subarctic Upper Water (PSUW) to the north. Preliminary results show significant interannual variability of T/S water properties between 100-250 meters. In summer, interannual T/S variability is larger than the mean seasonal cycle (see Fig 19). While summer T/S variability is greatest on the interannual scale, T/S does covary on a seasonal scale with dissolved Oxygen (DO), spiciness and Particulate Organic Carbon (POC). In particular, warmer, more saline water is associated with lower DO in fall and winter.

Risien, C.M., R.A. Desiderio, L.W. Juranek, and J.P. Fram (2020), Sustained, High-Resolution Profiler Observations from the Washington Continental Slope , Abstract [IS43A-05] presented at Ocean Sciences Meeting 2020, San Diego, CA, 17-21 Feb.

Thomson, R. E., and Krassovski, M. V. (2010), Poleward reach of the California Undercurrent extension, J. Geophys. Res., 115, C09027, doi:10.1029/2010JC006280.

Read More

Discovery of the Roots of the Axial Seamount

Excerpted from the OOI Quarterly Report, 2020.

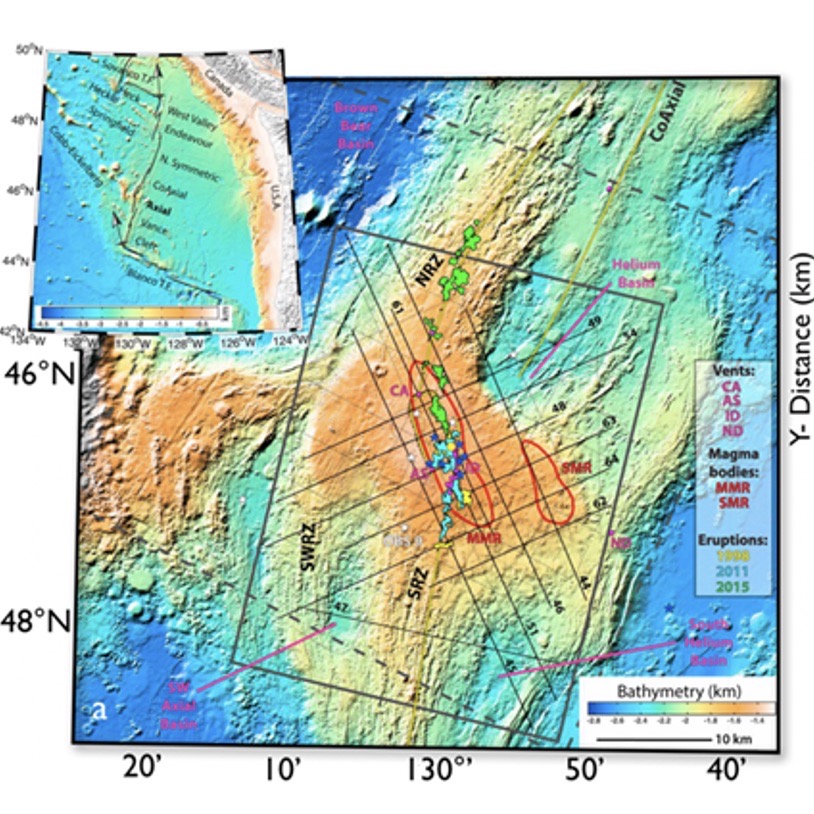

[media-caption type="image" class="external" path="https://oceanobservatories.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/Screen-Shot-2020-09-17-at-1.21.46-PM.png" alt="Axial Seamount Roots" link="#"]. Figure 14: a) Location of 1998, 2011, and 2015 lava flows at the summit of Axial Seamount, two magma chambers (re outlines MMR & SMR) and seismic lines (after [1]). b) Map view and perspective view of the MMR magma reservoir, seismicity and fault mechanisms from 10/2014 to 9/2015 (after [1]).[/media-caption]Two- and 3D-imaging of Axial Seamount, coupled with real-time monitoring of seismicity and seafloor deformation, is providing unprecedented insights into submarine volcanism, the nature of melt transport, and caldera dynamics (Figure 14) [1-15]. Recently acquired 3D imaging of the volcano [2] and analyses of 1999 and 2002 multichannel seismic data [4-7] have led to the remarkable discovery of a root zone 6 km beneath the volcano [2,5]. Carbotte et al., [5] describe a 3-to-5 km wide conduit that is interpreted to be comprised of numerous quasi-horizontal melt lenses spaced 400-500 m apart. The conduit is located beneath a 14-km-long magma reservoir (MMR) that spans the caldera of Axial Seamount and a secondary, smaller magma chamber (SMR) located beneath the eastern flank of the volcano [1,3]. This smaller reservoir presumably Dymond hydrothermal field hosting up to 60 m-tall actively venting chimneys, which was discovered on a 2011 RCA cruise. Seismicity prior to, during and subsequent to the 2015 eruption delineates outward dipping normal faults in the southern half of the caldera that extend from near the seafloor to 3-3.25 km depth [3,8-9]. In contrast, a conjugate set of inward dipping faults in the northern portion of the caldera extend to depths of ~ 2.25 km. The outward dipping ring faults were active during inflation and syn-eruptive deformation [[3,8-9]. Source fissures for the 1998, 2011, and 2015 eruptions are located within ± 1 km of where the MMR roof is shallowest (<1.6 km beneath the seafloor) and skewed toward the eastern caldera wall [3]. In concert, these studies are changing long-held views of magma chamber geometry and the deep-rooted feeder systems in mid-ocean ridge environments [2,5].

[1] Arnulf, A. F., Harding, A. J., Kent, G. M., Carbotte, S. M., Canales, J. P., and Nedimovic, M. R. (2014) Anatomy of an active submarine volcano. Geology, 42(8), 655–658. https://doi.org/10.1130/G35629.1.

[2] Arnulf, A.F., Harding, A.J., Saustrup, S., Kell, A.M., Kent, G.M., Carbott, S.M., Canales, J.P., Nedimovic, M.R., Bellucci M., Brandt, S., Cap, A., Eischen, T.E., Goulin, M., Griffiths, M., Lee, M., Lucas, V., Mitchell, S.J., and Oller, B. (2019) Imaging the internal workings of Axial Seamount on the Juan de Fuca Ridge. American Geophysical Union, Fall Meeting 2019, OS51B-1483.

[3] Arnulf, A.F., Harding, A.J., Kent, G.M., and Wilcock, W.S.D. (2018) Structure, seismicity and accretionary processes at the hot-spot influenced Axial Seamount on the Juan de Fuca Ridge. Journal of Geophysical Research, 10.1029/2017JB015131.

[4] Carbotte, S. M., Nedimovic, M. R., Canales, J. P., Kent, G. M., Harding, A. J., and Marjanovic, M. (2008) Variable crustal structure along the Juan de Fuca Ridge: Influence of on-axis hot spots and absolute plate motions. Geochemistry, Geophysics, Geosystems, 9, Q08001. doi.org/10.1029/2007GC001922.

[5] Carbotte, S.M., Arnulf, A.F., Spiegelman, M.W., Harding, A.J., Kent, G.M., Canales, J.P., and Nedimovic, M.R. (2019) Seismic images of a deep melt-mush feeder conduit beneath Axial Volcano. American Geophysical Union, Fall Meeting 2019, OS51B-1484.

[6] West, M., Menke, W., and Tolstoy, M. (2003) Focused magma supply at the intersection of the Cobb hotspot and the Juan de Fuca ridge. Geophysical Research Letters, 30(14), 1724. https://doi.org/10.1029/2003GL017104.

[7] West, M., Menke, W., Tolstoy, M., Webb, S., and Sohn, R. (2001). Magma storage beneath Axial volcano on the Juan de Fuca mid-ocean ridge. Nature, 413(6858), 833–836. doi.org/10.1038/35101581.

[8] Wilcock, W.S.D., Tolstoy, M., Waldhauser, F., Garcia, C., Tan, Y.J., Bohnenstiehl, D.R., Caplan-Auerbach, J., Dziak, R., Arnulf, A.F., and Mann, M.E. (2016) Seismic constraints on caldera dynamics from the 2015 Axial Seamount eruption. Science, 354, 1395-399; https://doi.org/10.1126 /science.aah5563.

[9] Wilcock, W.S.D., Dziak, R.P., Tolstoy, M., Chadwick, W.W., Jr., Nooner, S.L., Bohnenstiehl, D.R., Caplan-Auerbach, J., Waldhauser, F., Arnulf, A.F., Baillard, C., Lau, T., Haxel, J.H., Tan, Y.J, Garcia, C., Levy, S., and Mann, M.E. (2018) The recent volcanic history of Axial Seamount: Geophysical insights into past eruption dynamics with an eye toward enhanced observations of future eruptions. Oceanography, 31,(1), 114-123.

[10] Chadwick, W.W., Jr., Nooner, S.L., and Lau, T.K.A. (2019) Forecasting the next eruption at Axial Seamount based on an inflation-predictable pattern of deformation. American Geophysical Union, Fall Meeting 2019, OS51B-1489.

[11] Chadwick, W.W., Jr., Paduan, J.B., Clague, D.A., Dreyer, B.M., Merle, S.G. Bobbitt, A.M. Bobbitt, Caress, D.W. Caress, Philip, B.T., Kelley, D.S., and Nooner, S. (2016) Voluminous eruption from a zoned magma body after an increase in supply rate at Axial Seamount. Geophysical Research Letters, 43, 12,063-12,070; https://doi. org/10.1002/2016GL071327.

[12] Nooner, S.L., and Chadwick, W.W. Jr. (2016) Inflation- predictable behavior and co-eruption deformation at Axial Seamount. Science, 354, 1399-1403; https://doi.org/10.1126/ science.aah4666.

[13] Nooner, S.L., and Chadwick, W.W. Jr. (2016) Inflation- predictable behavior and co-eruption deformation at Axial Seamount. Science, 354, 1399-1403; https://doi.org/10.1126/ science.aah4666.

[14] Hefner, W.L., Nooner, S.L., Chadwick, W.W., Jr., and Bohnenstiehl, D.R. (2020) Magmatic deformation models including caldera-ring faulting for the 2015 eruption of Axial Seamount. Journal of Geophysical Research, https://doi:10.1029/2020JB019356.

[15] Levy, S., Bohnenstiehl, D.R., Sprinkle, R., Boettcher, M.S., Wilcock, W.S.D., Tolstoy, M., and Waldhouser, F. (2018) Mechanics of fault reactivation before, during, and after the 2015 eruption of Axial Seamount. Geology, 46(5), 447-450; https://doi.org/10.1130/G39978.1.

Read More

Axial Seamount: One of the Longest Records for Tsunami Research in the Ocean

Adapted and condensed by OOI from Fine et al., 2020, doi:/10.1029/2020GL087372.

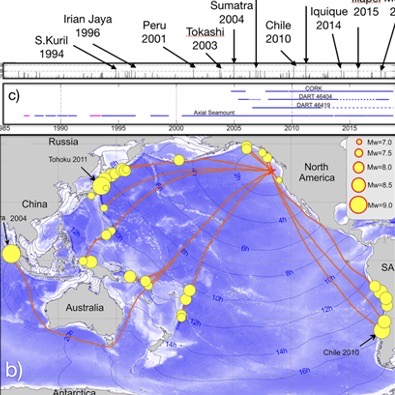

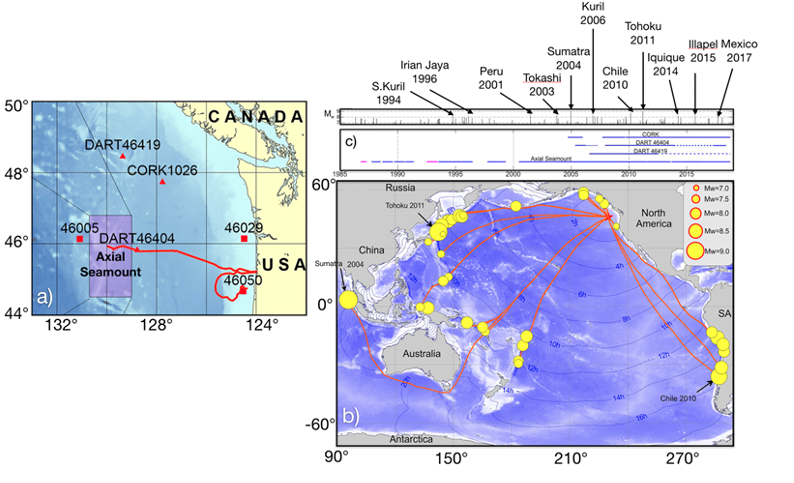

[caption id="attachment_18951" align="aligncenter" width="794"] Figure 22. a) Location of bottom pressure recorders (BPRS) at Axial Seamount and vicinity (Cleft segment not shown in this illustration), including DART buoys and an IODP Corked site (after [1]). Most of the pressure data for this investigation were from Axial Seamount. b) Source regionals for the tsunamis recorded at Axial with yellow circles indicating earthquake locations and circle size proportional to magnitudes. The thin blue lines mark the leading edge of tsunamis at 2 hr intervals after an earthquake. c) Temporal coverage of the BPR records and recorded tsunamis at Axial and adjacent areas 1986-2018. Magenta lines are BPR recordings from the Cleft Segment, south of Axial on the Juan de Fuca Ridge.[/caption]This study by Fine et al., [1] examines a 32 year record of high resolution bottom pressure recorder (BPR) measurements made by cabled instruments installed on Axial Seamount in 2014, and uncabled instruments at Axial, the Cleft Segment of the Juan de Fuca Ridge, DART buoys, and an IODP cored observatory (Hole 1026): most of the measurements in this study are from Axial (Figure 22). A total of 41 tsunamis were documented from 1986-2018 with all events associated with tsunamigenic earthquakes with magnitudes of 7.0 or greater. In contrast to coastal tide gauge observations, open ocean measurements by BPRs are advantageous because of the high signal-to-noise ratio. Based on this study, it is possible to forecast the effect of a tsunami originating from a source near a historical source, not only for Axial, but also for locations along the British Columbia‐Washington‐Oregon coast. These results allow a size-frequency model world-wide. The RCA cabled bottom pressure-tilt instruments, with 20 Hz sampling rates and with resolutions of 2 mm of seawater depth, provide especially high-resolution measurements.

Figure 22. a) Location of bottom pressure recorders (BPRS) at Axial Seamount and vicinity (Cleft segment not shown in this illustration), including DART buoys and an IODP Corked site (after [1]). Most of the pressure data for this investigation were from Axial Seamount. b) Source regionals for the tsunamis recorded at Axial with yellow circles indicating earthquake locations and circle size proportional to magnitudes. The thin blue lines mark the leading edge of tsunamis at 2 hr intervals after an earthquake. c) Temporal coverage of the BPR records and recorded tsunamis at Axial and adjacent areas 1986-2018. Magenta lines are BPR recordings from the Cleft Segment, south of Axial on the Juan de Fuca Ridge.[/caption]This study by Fine et al., [1] examines a 32 year record of high resolution bottom pressure recorder (BPR) measurements made by cabled instruments installed on Axial Seamount in 2014, and uncabled instruments at Axial, the Cleft Segment of the Juan de Fuca Ridge, DART buoys, and an IODP cored observatory (Hole 1026): most of the measurements in this study are from Axial (Figure 22). A total of 41 tsunamis were documented from 1986-2018 with all events associated with tsunamigenic earthquakes with magnitudes of 7.0 or greater. In contrast to coastal tide gauge observations, open ocean measurements by BPRs are advantageous because of the high signal-to-noise ratio. Based on this study, it is possible to forecast the effect of a tsunami originating from a source near a historical source, not only for Axial, but also for locations along the British Columbia‐Washington‐Oregon coast. These results allow a size-frequency model world-wide. The RCA cabled bottom pressure-tilt instruments, with 20 Hz sampling rates and with resolutions of 2 mm of seawater depth, provide especially high-resolution measurements.

[1] Fine, I.V., Thomson, R.E., Chadwick, W.W., Jr., and Fox, C.G., (2020) Toward a universal frequency occurrence distribution for tsunamis: statistical analyses of a 32-year bottom pressure record at Axial Seamount. Geophysical Research Letter, https://doi.org/10.1029/2020GL087372.

Read More

Irminger Sea Intermediate Water Formation and Transport

Adapted and condensed by OOI from Le Bras et al., 2020, doi:/10.1029/2019GL085989.

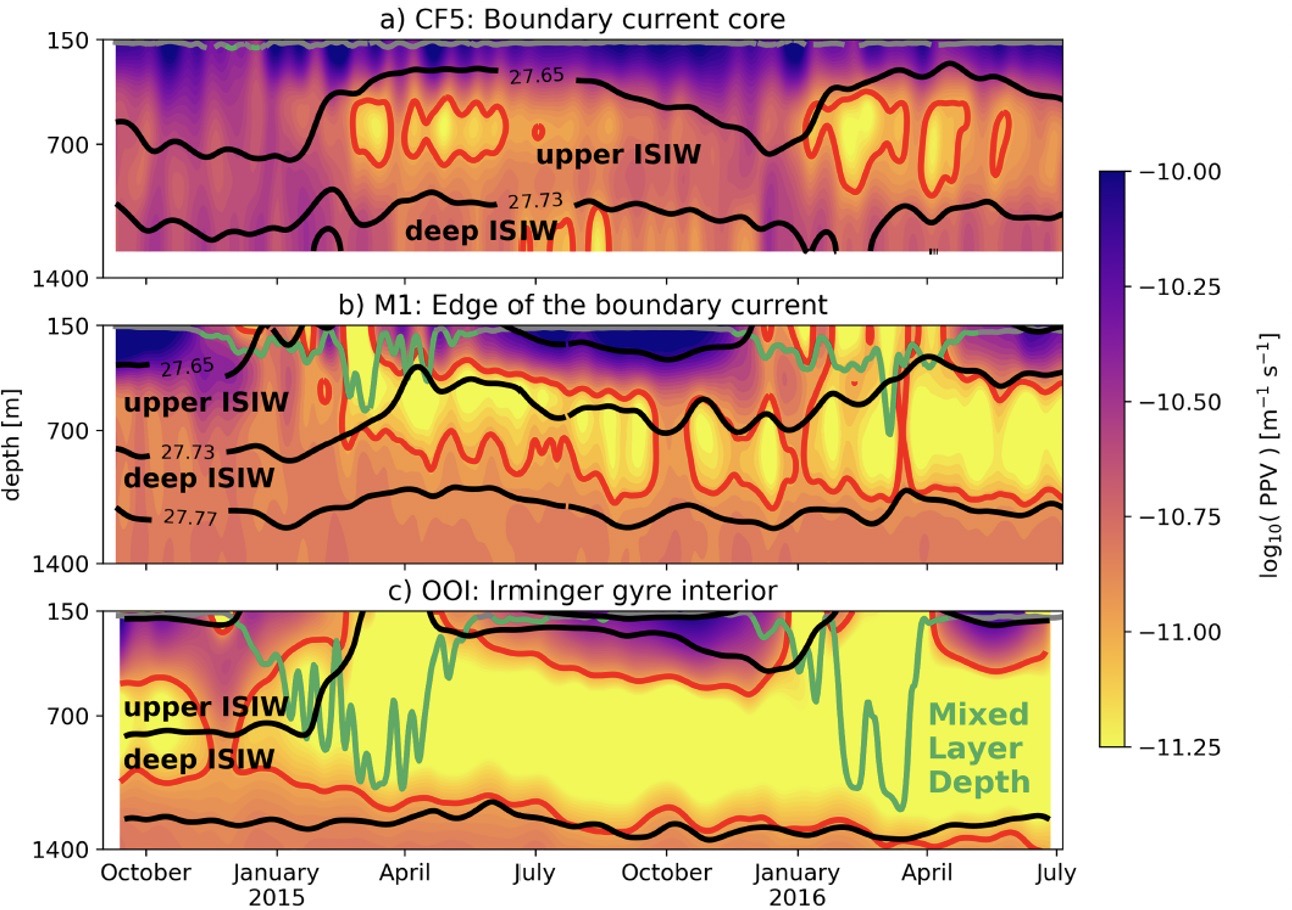

[caption id="attachment_18947" align="aligncenter" width="640"] Figure 19. Planetary potential vorticity (PPV) at (a) OSNAP mooring CF5, within the Irminger Sea boundary current core (b) OSNAP mooring M1, at the edge of the boundary current and (c) OOI flanking mooring (FLMA) and Surface Mooring within the Irminger Sea gyre. From Le Bras et al. (2020).[/caption]

Figure 19. Planetary potential vorticity (PPV) at (a) OSNAP mooring CF5, within the Irminger Sea boundary current core (b) OSNAP mooring M1, at the edge of the boundary current and (c) OOI flanking mooring (FLMA) and Surface Mooring within the Irminger Sea gyre. From Le Bras et al. (2020).[/caption]

A two-year record from moorings in the Irminger Sea allowed researchers (Le Bras et al., 2020) to investigate both deep convection and transport of water masses associated with the Atlantic overturning circulation. Using mooring data from the OOI Irminger Sea Array and the Overturning in the Subpolar North Atlantic (OSNAP) array, the authors were able to identify two types of Irminger Sea Intermediate Water (ISIW) formed by deep convection. Upper ISIW is found near the edge of the Irminger Sea western boundary current, whereas Deep ISIW is formed in the basin interior. Water masses were diagnosed using temperature-salinity properties and the planetary potential vorticity (PPV). Figure 19 shows PPV for three different locations, in the boundary current, at its edge, and in the Irminger Sea gyre. Black lines in the figure indicate the isopycnals that bound upper and deep ISIW as defined by the authors, the red contours enclose water with low PPV (indicative of convection) and the green lines indicate the mixed layer depth.

Seasonal pulses of low PPV water in the boundary current occurring below the mixed layer (Figure 19a) suggest subduction from a non-local source offshore. In contrast, low PPV water in the gyre interior is accompanied by a deep winter mixed layer and appears related to local convection. Further analysis by the authors indicates that waters formed by convection in the interior gyre are entrained into the boundary current within a few months of formation. Importantly, it appears that eddy dynamics are responsible for this transport of ventilated water from the interior to the boundary, and that the upper ISIW in the boundary current is a significant component of the Atlantic overturning circulation.

Read MoreEvent and Seasonal Scale Variability of Surface Heat and Momentum Fluxes

Excerpted from the OOI Quarterly Report, 2020.

Endurance Array: Event and Seasonal Scale Variability of Surface Heat and Momentum Fluxes off Oregon and Washington

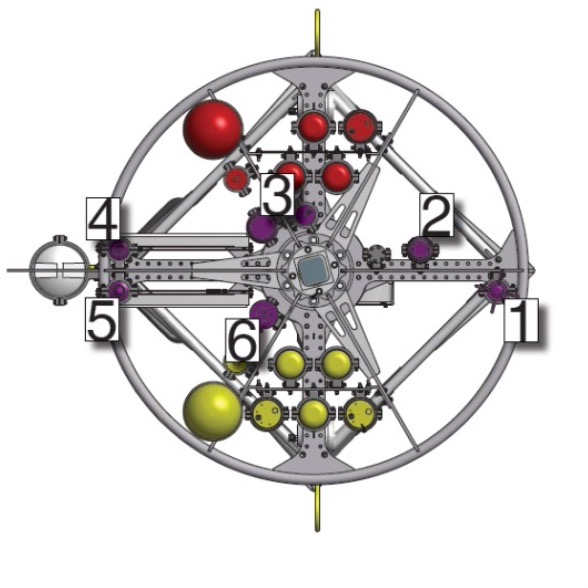

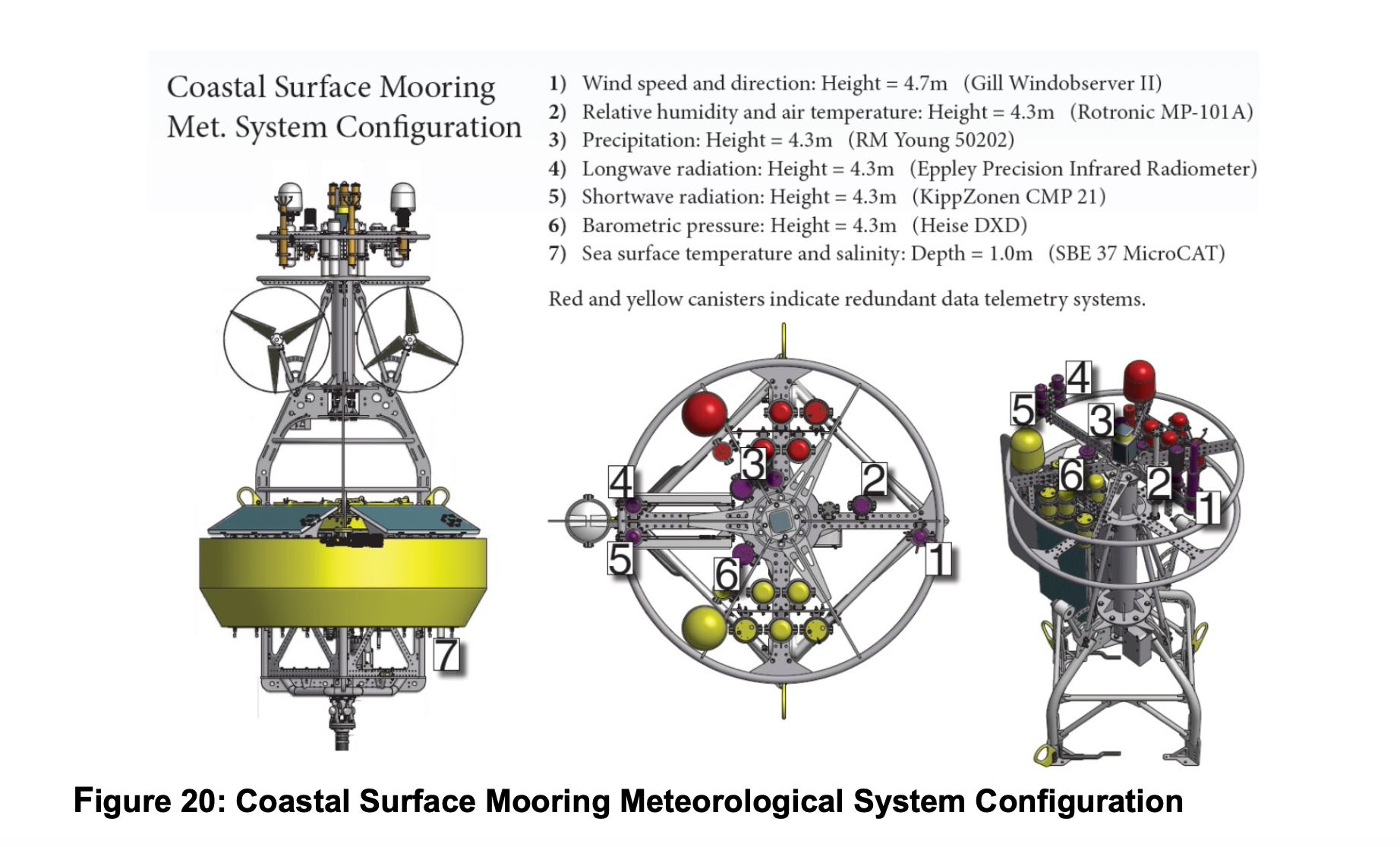

As part of the NSF-funded Ocean Observatories Initiative (OOI) Coastal and Global Scale Arrays, surface buoy meteorological measurements are made using the Air-Sea Interaction Meteorology (ASIMET) package (Figure 20). These measurements are reported on in Dever, E.P, J.P. Fram, C.M. Risien, R.A. Desiderio, C.E. Wingard (2020), Event and Seasonal Scale Variability of Surface Heat and Momentum Fluxes off Oregon and Washington, Abstract [A144A-2411] presented at Ocean Sciences Meeting 2020, San Diego, CA, 17-21 Feb. Radiative and bulk surface fluxes calculated from these measurements are provided as OOI data products. Both the measurements and the estimated fluxes are available through the OOI Data Portal as are all the metadata required to produce these fluxes (raw data, calibration coefficients, data product specifications, data product algorithms etc.).

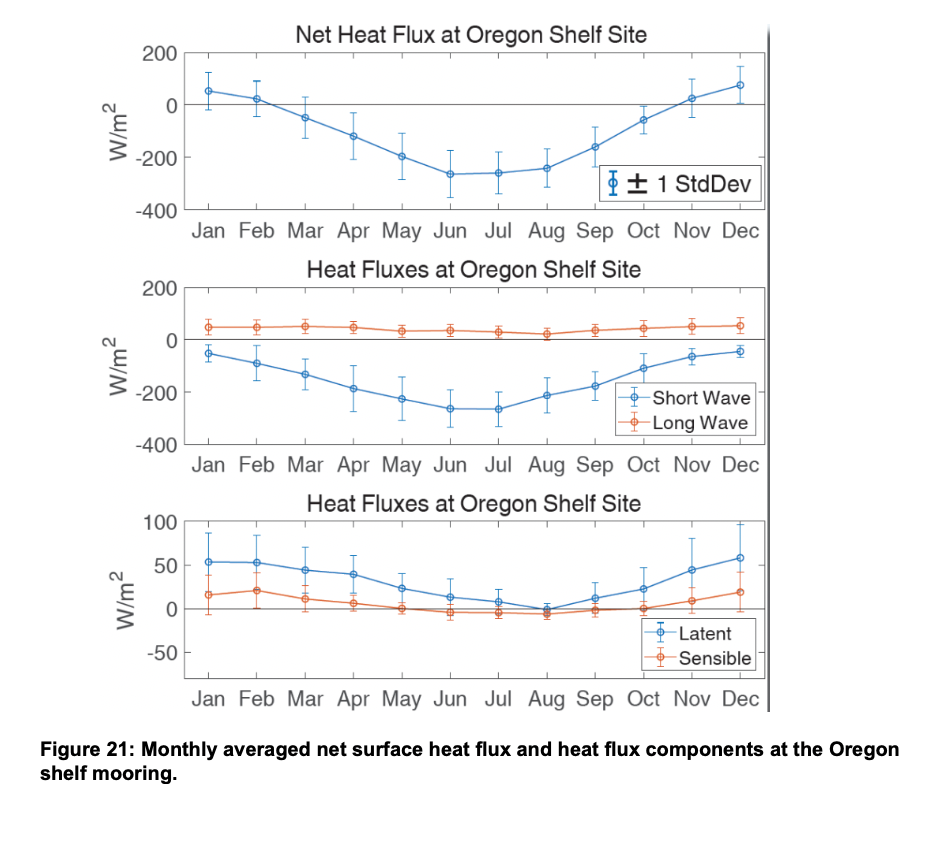

On the Endurance Array, ASIMET measurements are made at four locations over the Oregon and Washington shelf and slope. These locations lie within the northern California Current Marine Ecosystem. Here upwelling favorable wind forcing and atmospheric conditions occur in spring and summer months with forcing in other months driven by passing low pressure systems. The timing of both the spring transition to upwelling and the fall transition to storm forcing varies from year to year as does the strength of individual events within each season. Upwelling events are associated with strong net shortwave and latent heat fluxes. Storm events are associated with weak net shortwave fluxes and latent fluxes that vary in strength.

Machine to machine (M2M) calls were used to read in hourly bulk surface fluxes from OOI Endurance Array moorings from their initial deployments in April 2015 through February 2020. OOI data product fluxes are calculated with TOGA-COARE and other community standard algorithms. Monthly averages of OOI Endurance Array flux data compare well with one another. Both the Oregon and Washington shelves are subject to heating on an annually averaged basis. The Oregon Shelf mooring (Figure 21) is typical. Late fall and winter show net fluxes from the ocean to the atmosphere. All other months show heat flux into the ocean due to insolation.

Read More

From Whale Songs to Volcanic Eruptions: OOI’s Cable Hears the Sounds of the Ocean

Sound is omnipresent in the ocean. Human-induced noise has the potential to affect marine life.

After the global recession in 2008, the ocean became quieter as shipping declined. Off the coast of Southern California, for example, scientists at Scripps Institution of Oceanography found that noise amplitudes measured from 2007-2010 were lowered by 70 percent with a reduction in one ship contributing about 10 percent.

A similar quieting of the ocean can be expected as global ship traffic continues its decline in response to the corona virus pandemic. This quieter ocean offers scientists ways to expand their ongoing research on ocean sound and its impact on marine life.

[media type="image" path="https://oceanobservatories.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/Finhval_1.jpg" link="#" alt="Fin Whale"][/media]“It takes time to document real change in the ocean, but University of Washington oceanographers have reported that over the past decade, fin whales have been communicating more softly in the Pacific,“ said Deborah Kelley, professor of oceanography at the University of Washington and director of the OOI’s Regional Cabled Array (RCA) component. “A quieter ocean allows us to hear more clearly life and other natural processes within the ocean.”

Years of listening to whales

John Ryan, a biological oceanographer at the Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute (MBARI), has been “listening in” on whales and other marine creatures since 2015 using a hydrophone on the Monterey Accelerated Research System (MARS), a cabled observatory, which was in part established as a test bed for the OOI Regional Cabled Array. Ryan and colleagues studied the occurrence of humpback whale (Megaptera novaeangliae) song in the northeast Pacific using three years of continuous recordings off the coast of central California.

[media type="image" path="https://oceanobservatories.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/Humpback_Whale_underwater_shot.jpg" link="#" alt="Humpback Whale"][/media]“We’ve been listening almost continuously since July 28, 2015, using a broadband, digital, omnidirectional hydrophone connected to MARS. Listening continuously for that long at such a high sample rate is not easy; only by being connected to the cable is this possible,” explained Ryan.

The researchers were able to discern whale songs from the busy ocean soundscape in Monterey Bay National Marine Sanctuary, which is a feeding and migratory habitat for humpback whales. The humpbacks’ song was detectable for nine months of the year (September–May) and peaked during the winter months of November through January. The study revealed strong relationships between year-to-year changes in the levels of song occurrence and ecosystem conditions that influence foraging ecology. The lowest song occurrence coincided with anomalous warm ocean temperatures, low abundances of krill – a primary food resource for humpback whales, and an extremely toxic harmful algal bloom that affected whales and other marine mammals in the region. Song occurrence increased with increasingly favorable foraging conditions in subsequent years.

Because the hydrophone is on the cabled observatory, its operation can be adjusted to achieve new goals. For example, the sampling rate of the hydrophone was doubled during an experiment that successfully detected very high frequency echolocation clicks of dwarf sperm whales (with Karlina Merkens, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration). “And that’s a beautiful aspect of being on the cable,” added Ryan. “Not only do we know that it is working, we catch any network glitches pretty quickly so we don’t lose data, and we can do real-time experiments like these.”

William Wilcock of the University of Washington and his students have compiled a decade worth of data on fin whales in the northern Pacific. Fin whales call at about 20 HZ, which is too low of a frequency for humans to hear, but perfect for seismometers to record. The researchers aggregated ten years of data from both temporary recorders and now permanent RCA hydrophones and seismic sensors and looked at the frequency of the calls and calling intervals. The researchers found both have changed over time.

The fin whales call seasonally and the frequency of the calls has gone down with time.

[audio mp3="https://oceanobservatories.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/Fin_whale_10x.mp3"][/audio]Calls peak in late fall, early winter in relation to mating season. Gradually through the season the frequency decreases. At the start of the next season, the call frequency jumps up again, but not quite to where it was the year before. Over ten years, the frequency has gone down about 2 HZ, and scientists are puzzled as to why this is occurring. It is unlikely to be due to increasing ship noise, because this lower sound frequency is getting closer to the range of the noise level of container ship propellers, about 6-10 HZ.

In some settings, ship noise is known to affect whale behavior and the permanent network of hydrophones operated by the OOI and Ocean Networks Canada will provide an opportunity to study whether whales are avoiding the shipping lanes to Asia.

Volcanoes also rumble in the deep

Whale sounds are but one of many acoustic signals being recorded and monitored using hydrophones and broadband seismometers. The OOI’s RCA off the Oregon Coast includes 900 kilometers (~560 miles) of submarine fiber-optic cables that provide unprecedented power, bandwidth, and communication to seafloor instrumentation and profiler moorings that span water depths of 2900 m to 5 m beneath the ocean surface. Using a suite of instruments connected to the cable, which continuously stream data in real time, scientists are listening in on the sounds of submarine volcanism, which accounts for more than 80 percent of all volcanism on Earth.

More than 300 miles off the Oregon coast in 1500 meters of water, 20+ cabled seafloor instruments are located at the summit of Axial Seamount, the most active volcano on the Juan de Fuca Ridge, including hydrophones and seismometers, which can also record sounds in the ocean.

“Scientists were able to hear(as acoustic noises traveling through the crust) >8000 earthquakes that marked the start of the Axial eruption in 2015. Coincident with this seismic crisis bottom pressure tilt instruments showed that the seafloor fell about 2.4 meters (~8 feet).

[video width="670" height="384" m4v="https://oceanobservatories.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/Axial-seamount-audio-.m4v"][/video]It was a remarkable collaborative event with scientists from across the country witnessing the eruption unfold live,” added Kelley. Such real-time documenting of an eruption in process was possible because of how Axial is wired. It is the only place in the oceans where numerous processes taking place prior to, during, and following a submarine eruption are captured live through data streaming 24/7. William Wilcock, University of Washington, and Scott Nooner, University of North Carolina, Wilmington, and colleagues reported these findings in Science, 2016.

Data collected from the hydrophones at the seamount’s base supported another discovery about Axial, indicating that it explosively erupted in 2015. Hydrophones recorded long-duration diffusive signals traveling through the ocean water consistent with explosion of gas-rich lavas, similar to Hawaiian style fissure eruptions. Follow-on cruises documented ash on some RCA instruments, again indicating the likelihood of explosive events during the 2015 eruption.

“Having the opportunity to listen in while a submarine volcano is active offers a really interesting window into things,” said Jackie Caplan-Auerbach, associate dean at Western Washington University and lead author of a G-cubed article that reported the possible eruptive findings. “While we cannot say with utter certainty that there were explosions at Axial, there’s a lot of evidence that supports this. We know from having listened to other eruptions that this was the same type of sound. It’s distinct, like the hissing sound of a garden hose on at top speed. We also found these really fine particulates, which could only have resulted from an eruption, had collected on one of the instruments at the site.”

[audio wav="https://oceanobservatories.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/axial_explosive.wav"][/audio]Added Caplan-Auerbach, “My favorite part of having OOI is it offers an ability for pure discovery. Its real time nature makes it possible to observe and see what happens. And sometimes the planet just hands you a gift that you didn’t expect. Not always being hypothesis driven is a very valuable aspect of science that I hope does not get lost. I’m very appreciative of projects like this that open our eyes into signals that we didn’t know were there.”

More opportunities to expand knowledge about sound and the sea are on the horizon. The US. Navy has funded Shima Abadi, University of Washington, Bothell, for a comprehensive study of sounds recorded by the OOI hydrophones. Stay tuned!

Image credits: Top fin whale: Wikipedia, Aqqa Rosing-Asvid – Visit Greenland. Second from top: humpback whale: Public domain, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

Read More

Explosive Bubble Plume Emissions from Southern Hydrate Ridge

From Marcon and Bohrmann, 13, December 2019.

Remarkable changes in seafloor topography and biological communities, quantification of methane flux, and connections from the seafloor to upper water column methanotrophy.

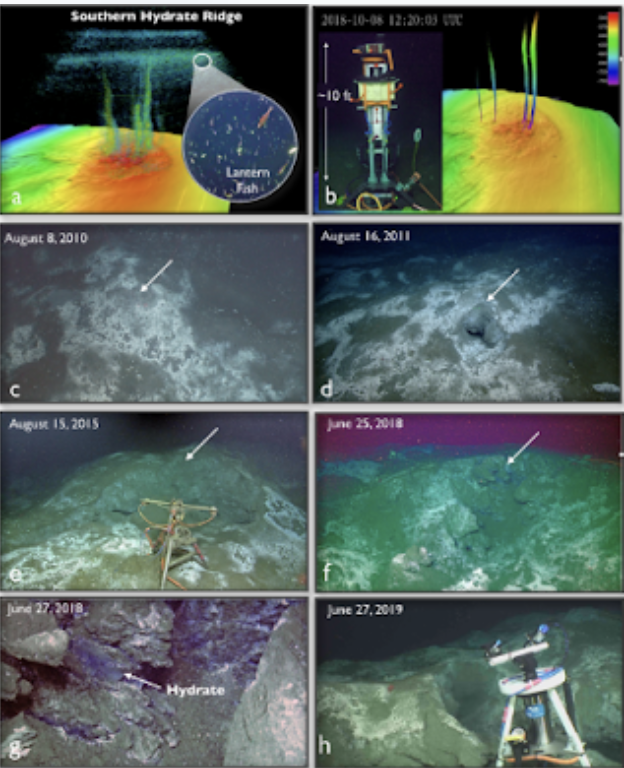

Southern Hydrate Ridge (SHR) is one of the most active and dynamic methane seep sites known. Repeat investigations during Regional Cabled Array (RCA) cruises show that it is highly dynamic, delineated by exceptional changes in seafloor morphology, venting intensity and temporal variability, and by the distribution and density of associated biological communities (Fig. 1) [1-6]: here, AI is being utilized to quantify the areal extent of seeps and classification of organisms [4,7]. Since first imaged in 2010, the summit of SHR has changed remarkably with areas of smooth, gentle hummocks transformed into extensive, highly rugged and steep-sided collapsed pits from which jets and explosions of bubbles occur (Figs. 1c-h). Equally dynamic are changes in the locations and thicknesses of microbial mats that mark more diffuse seepage of methane from the seafloor. Surprisingly, chemical results from continuous measurements from RCA flow meters show an annual net transport of fluid downward into the sediment resulting in the development of new transport models for these seep environments [8]. At the focused RCA experimental site “Einsteins’ Grotto” and at a site to the north, hydrate is exposed at the seafloor within the collapsed pits (Fig. 1d).

Because of OOI, SHR is one of only three places (the others being Ocean Networks Canada Barkley Canyon and Clayoquot Slope sites) in the oceans where time series investigations of methane release are conducted at hour to year time periods utilizing ship and RCA PI cabled multibeam sonars, cameras and an upward-looking ADCP [2, 5-6, 9-11]. Results from a 3-year investigation of SHR show that the locations of seep activity and bubble release remained unchanged, however, the magnitude of gas release was highly variable on hourly time scales (Fig. 1a) [2]. Bubble plumes rise up to ~480 above the seafloor and in several cases exceed the upper limit of hydrate stability by ∼190 m. Here, shallow subsurface waters, where methane disassociates, is marked by high density regions of lantern fish, consistent with increased biological activity associated with the microbial oxidation of the released methane (Fig. 1a) [2].

As a key cabled site on the RCA, SHR has attracted numerous national and international investigators including a several year program funded by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research to quantify methane flux from the highly active Southern Hydrate Ridge RCA site (G. Bohrmann and Y. Marcon, MARUM, University of Bremen, Germany; “Sonar monitoring of natural release of methane greenhouse gas from the seafloor – A contribution to the understanding of global change.”). In 2018, it was mapped at submeter resolution and the entire site photo mosaicked as part of a Schmidt-funded program (B. Thornton, University of South Hampton). Cabled infrastructure now installed as part of the MARUM project includes an overview multibeam sonar that completes a 360° scan every 2 hrs and spans a distance of 700 m, imaging all sites of bubble plume emissions at SHR (Fig. 1b) [5-6; 10-11]. Other infrastructure includes a multibeam, very high-resolution sonar that quantifies bubble emissions from Einstein’s Grotto, a 4k video and digital still camera that takes 3 images each hour of the explosive hydrate-bearing site – Einsteins’ Grotto (Fig. 1h), and a CTD to examine the impacts of ocean warming and release of methane into the hydrosphere. Automated plume imaging is now utilized for time-series hourly imaging by the RCA digital still camera [5-6]. The images, available through the OOI Data Portal, document remarkable changes of the collapse pit over time and in associated biology.

[blockquote][1] Kelley, D.S. (2016) Real-time multidisciplinary monitoring of a highly dynamic methane seep: The OOI Cabled Array at Southern Hydrate Ridge. Gordon Conference Natural Hydrate Systems. Interfacial science advances towards understanding and monitoring gas hydrate systems. Galveston, February 28 – March 4, 2016.

[2] Philip. B.T., Denny, A.R., Solomon, E.A., and Kelley, D.S. (2016) Time-series measurements of bubble plume variability and water column distribution above Southern Hydrate Ridge. Geochemistry, Geophysics, Geosystems, 17 (3) 10.1002/2016GC006250.

[3] Bigham, K., Kelley, D.S., Solomon, E.A., and Delaney, J.R. (2017) Extreme Morphologic and Venting Changes in Methane Seeps at Southern Hydrate Ridge, Cascadia Margin. American Geophysical Union, Fall Meeting 2017, OS53B-1199.

[4] Bigham, K., Kelley, D.S., Marburg, A., and Delaney, J.R. (2017) Further Interpretation of the Relationship between Faunal Community and Seafloor Geology at Southern Hydrate Ridge, Cascadia Margin: Exploring Machine Learning, American Geophysical Union, Fall Meeting 2017, U21B-09.

[5] Bohrmann, G., and Marcon, Y., (2019) Long-term monitoring of gas emissions at Southern Hydrate Ridge. American Geophysical Union, Fall Meeting 2019. OS51A-04.

[6] Marcon, Y., and Bohrmann, G. (2019) Long-term monitoring of gas emissions at Southern Hydrate Ridge. American Geophysical Fall Meeting 2019, OS51A-04.

[7] Marburg, A., and Bigham, K., (2016) Deep learning for benthic fauna identification, Oceans 16 MTS/IEEE Monterey, 10.1109/OCEANS.2016.7761146.

[8] Whorley, T.L., Solomon, E.A., Kowalski, L., and Centurion, R., (2019) Persistent downward flow of seawater beneath Beggiatoa mat communities at Hydrate Ridge – mechanisms and biogeochemical implications. American Geophysical Union, Fall Meeting 2019, OS43B-1706.

[9] Philip. B.T., Kelley, D.S., Solomon, E.A., and Delaney, J.R. (2016) Monitoring methane emissions at Southern Hydrate Ridge using an OOI Cabled Array Acoustic Doppler Current Profiler. OCEANS 2016 MTS/IEEE Monterey, 10.1109/OCEANS.2016.7761469

[10] Marcon, Y., Sahling, H., von Wahl, T., Spiesecke, U, Vittori, V., Leymann, T., and Bohrmann, G., (2018) M³: Towards Long-Term Acoustic Monitoring of Gas Emissions using Underwater Cabled Observatory Technology. Ocean Sciences Meeting, doi.org/10.1002/essoar.b8ca5006b4256b34.3745ac673d8f4f8a.1.

[11] Marcon, Y., Kopiske, E., Leymann, T., Spiesecke, U., Vittori, V., von Wahl, T., Wintersteller, P., Waldmann, C., and Bohrmann, G., (2019) A rotary sonar for long-term acoustic monitoring of deep-sea gas emissions. OCEANS19 – Marseille, IEEE. 10.1109/OCEANSE.2019.8867218.

[/blockquote] Read More

A Marine Heat Wave Identified on the New England Shelf

From Gawarkiewicz et al., 22 November 2019

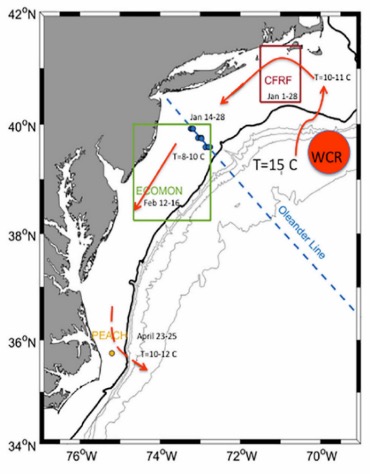

Marine heat waves are warm anomalies persisting for days to months and on spatial scales from 1-1000 km (Hobday et al., 2016). These heat waves disturb the marine environment and may have significant feedbacks on the atmosphere. Recent studies suggest that the New England continental shelf is increasingly impacted by Warm Core Rings (WCR) initiating from the Gulf Stream. Gawarkiewicz et al 2019 describe a strong marine heatwave in early 2017 that was apparently initiated by a WCR intrusion onto the shelf.

The first indication of the 2017 heatwave was from a Rhode Island fisherman who noticed unusual species (typically found in Gulf Stream waters) in his catch from the New England shelf. This indicated unusually warm waters on the shelf, and researchers began to investigate the regional extent. A number of different data sources, including OOI Pioneer Array assets, were necessary to track the anomalies along the length of the Middle Atlantic Bight (MAB).

Temperature anomalies measuring up to 6 C and salinity anomalies exceeding 1 PSU were found. The duration of the heatwave was approximately 4 months, initiating near Nantucket Shoals in Jan 2017, traversing the entire MAB, and dissipating offshore of Cape Hatteras in April. The advective path of the heatwave extended roughly 850 km.

Comparison with historical records from 1940 to 1996 showed that the 2017 heatwave was an unprecedented event in terms of temperature and salinity anomalies. The heat wave had significant impacts, including shoreward shift of the shelfbreak front, lowered chlorophyll concentrations, and the presence of warm water fish in New England coastal waters.

Read MoreTime Series Allows Investigation of Wind Forcing and Physical and Bio-Optical Variability

From Dever et al., 29 September 2019

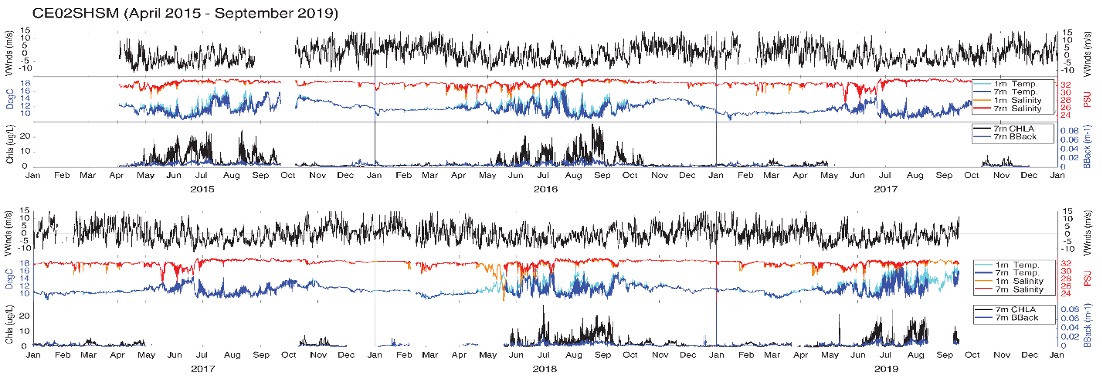

The full scope of OOI Endurance Array surface moorings has been deployed since April 2015. The moorings are deployed off Grays Harbor, Washington and Newport, Oregon at inner shelf, shelf and slope depths. They include surface meteorology, physical oceanographic, chemical and biological sensors. During the summer of 2019, EA staff reviewed mooring data since inception. In September 2019, we presented a poster of these data at the annual Eastern Pacific Ocean Conference (EPOC). The objectives of the poster were to show the time series data and discuss their availability and quality issues with research community members. To stimulate discussion, we reported on seasonal variability in wind forcing, water temperature, and chl-a fluorescence. We described the mooring measurements and how to access the data.

The Oregon and Washington shelves are part of the northern California Current Marine Ecosystem. They exhibit characteristic responses to spring and summer upwelling winds and winter storms. In the above figure, we show representative time series of near surface measurements at the Oregon shelf mooring since its start in April 2015 through the present. As part of the poster, we also presented similar data from the other OOI surface moorings and calculated lagged correlations between wind, temperature, and chlorophyll, and commented on the observed variability.

We also pointed viewers to example Matlab and Python scripts to download and plot the OOI data presented in the poster via the Machine to Machine (M2M) interface on the OOI Data Portal.

Read MoreAnomalous Shallow Strong Currents Off the Oregon Margin

Blow down of the 200-meter Shallow Profiler Mooring Platform 2019

K. Roseburg and W. Ruef, Regional Cabled Array and P. MacCready, University of Washington, 20 August 2019

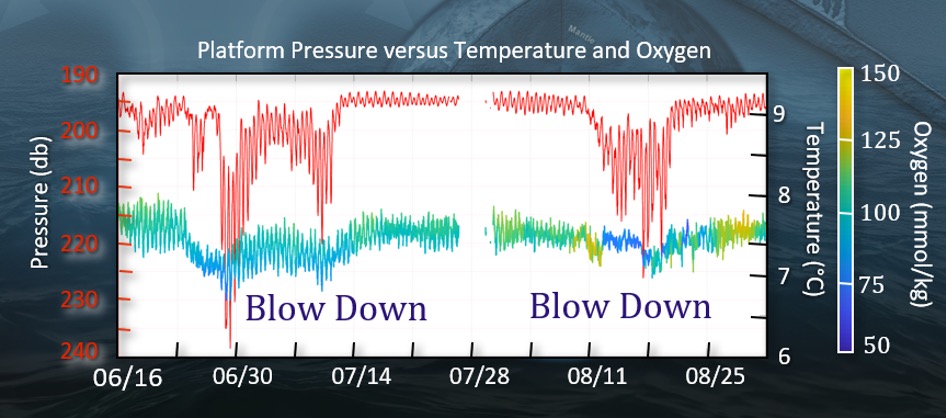

In June and August, 2019, the Slope Base Shallow Profiler Mooring was impacted by two substantial “blow down” events: these were the first observances of blow downs since the moorings were installed in 2014. The largest of these events, which occurred near the end of July and which lasted over two weeks, resulted in a deepening of the 12 ft across, 7,000 lb. platform nearly 50 m and migration of the platform ~ 150 m to the west. Results from pressure, ADCP, temperature and oxygen data pulled from CI using M2M, indicate that as the currents strengthened, the float was depressed into ~ 0.25-0.50°C cooler water with slightly decreased oxygen concentrations. An evaluation of the eddy kinetic energy calculated from the ADCP data, does not support eddy-driven water mass transport. The lower oxygen concentrations could reflect lower amounts of photosynthesis as the platforms are pushed deeper into the water column. We do not know of other documented blow down events such as these in the PNW.

Read More